The following are the general categories of cytologic interpretation:

- Non-diagnostic

- No cytologic abnormalities

- Inflammation

- Hyperplasia/dysplasia

- Neoplasia

Note: Often more than one category is present, as inflammation can result in dysplastic changes in the surrounding tissue and inflammation often accompanies a neoplastic process.

Non-diagnostic samples

There are many reasons for obtaining a non-diagnostic sample:

- Poor cellularity of the sample: Due to a poorly exfoliating lesion or poor sample collection.

- Excessive blood contamination: This contributes leukocytes, which need to be differentiated from a true inflammatory infiltrate, which can be difficult. When we describe cellularity, we usually do not include blood-associated leukocytes. They do not help with interpretation and can hinder it.

- Many smudged or ruptured cells: This may result from exuberant collection methods (e.g. excessive pressure put on the syringe during aspiration) or smear preparation (excessive pressure put on the spreader slide – squashing cells), though some tumor cells are excessively fragile and prone to rupture.

- Sampling error: Aspiration of surrounding fat or another structure, e.g. aspiration of the salivary gland when attempting mandibular lymph node aspiration.

If the sample has adequate cellularity and the cells are well-stained and well-preserved, the next step in cytologic diagnosis is the identification of the cell types and pathologic process that are present. It helps to ask a series of questions when working through smears:

- Is there evidence of hemorrhage?

- Does the smear contain inflammatory cells in excess of blood?

- Can a cause for the inflammation be identified?

- Are there tissue cells present?

- Are they expected normal for the aspirated site?

- If the cells are not expected for the aspirated site, what is their lineage – epithelial, mesenchymal, round or discrete cell, endocrine/neuroendocrine?

- Are they neoplastic or non-neoplastic (e.g. cyst)?

- Do the cells show cytologic criteria of malignancy?

- What other features are present, e.g. erythrophagia, necrosis, mineralization.

No cytologic abnormalities

Cells are present in normal numbers for the tissue aspirated and do not possess significant criteria of malignancy. This finding is most common when aspirating internal organs or lymph nodes, as most skin and subcutaneous masses represent a true pathologic process.

Inflammation

Inflammatory responses are classified by the type of inflammatory cells within the lesion, which also gives us clues as to the cause of the inflammation. Note that the causes listed below are not exhaustive lists, but more common examples.

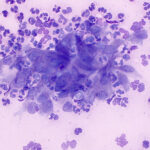

Suppurative

- >85% neutrophils

- The appearance of neutrophils may be helpful in identifying cause.

- Non-degenerate neutrophils (resemble those in blood with condensed clumped chromatin): Causes include immune-mediated conditions, sterile irritants (bile, urine), bacterial infection, protozoal or fungal infection. The lack of degenerative change in neutrophils does not mean that the inflammation is not due to bacterial infection. Some species of bacteria will not cause this morphologic change in neutrophils.

- Degenerate neutrophils: These are undergoing karyolysis and taking up water, resulting in cell and nuclear swelling. In these cases, suspect bacterial sepsis and look carefully for phagocytized organisms. However, such swelling can also be an artifact of sample collection into fluids and storage. Degenerate neutrophils do not always mean bacterial sepsis and can be seen with fungal infections and chemical irritants.

- It is always a good idea to culture a sample with neutrophilic inflammation, unless you know the cause is not bacterial sepsis, e.g. pancreatitis.

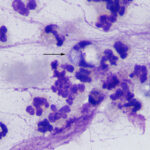

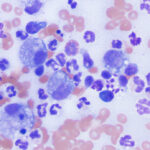

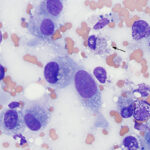

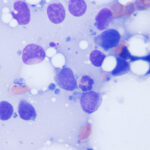

Histiocytic/macrophagic

- Macrophages dominate in these lesions and they may take on various appearances, depending on the cause, e.g. epithelioid, multinucleated, vacuolated and phagocytic (“reactive”). Epithelioid macrophages are generally not phagocytic or vacuolated and mimic epithelial cells. The presence of multinucleated macrophages supports a granulomatous inflammatory response.

- Causes: Foreign body reactions, fungal infection, certain bacterial infections, such as Mycobacterium.

- Macrophages in cytologic smears may show cellular phagocytic activity.

- Erythrophages: This indicates recent hemorrhage (<24 hours). Note that erythrophagia can also occur as an artifact during storage of fluid specimens (e.g. body cavity fluids). Macrophages retain phagocytic activity in vitro.

- Hemosiderophages: These are macrophages that contain hemosiderin in their cytoplasm. The hemosiderin is from the iron component of the porphyrin ring of hemoglobin (from phagocytized erythrocytes) and represents the storage form of iron. Hemosiderophages supports prior hemorrhage (>24 hours duration as it takes time for hemosiderophages to form).

- Melanophages: These macrophages contain phagocytized melanin in their cytoplasm. They can be a normal finding in lymph nodes but can also represent drainage from a melanoma in these organs.

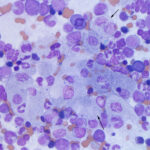

Mixed

- This is comprised of a mixture of neutrophils and macrophages, with neutrophils being typically non-degenerate, unless there is concurrent bacterial sepsis. Neutrophils usually dominate, but may not if the outer edges of the lesion are aspirated (the latter areas may be more macrophage-rich). This type of mixed inflammation is also called pyogranulomatous, particularly if there are multinucleated macrophages. Lymphocytes and plasma cells can be seen in low numbers well.

- Causes: Foreign body reactions (e.g. keratin from a furunculosis), fungal infection, longer-standing bacterial infection, infection with specific bacteria (e.g. Nocardia, Actinomyces). Chronic tissue injury can also incite a mixed inflammatory response.

Eosinophilic

- This is generally defined as inflammation consisting of more than 10-20% eosinophils, although cut-offs vary between clinical pathologists, with some pathologists indicating an eosinophilic component to the inflammation if <20%.

- Causes: Hypersensitivity reactions to allergens or infectious agents such as parasites, certain fungi and foreign bodies (e.g. keratin), insect bites, cancer (e.g. mast cell tumors).

Lymphocytic or lymphoplasmacytic

- This consists of a mixture of mostly small lymphocytes along with plasma cells. Other inflammatory cells, such as “activated” macrophages may be seen as well.

- Causes: Antigenic/immune stimulation, e.g. tick bite, viral infections or chronic inflammation.

Hyperplasia and dysplasia

The strict definition of hyperplasia is an increase in the number of cells in a tissue; however, the term is often used in a more generic fashion in cytology as a non-neoplastic enlargement of a tissue. Hyperplasia is often the result of hormonal influences (e.g. benign prostatic hyperplasia, perianal gland hyperplasia), tissue injury (e.g. regenerative nodules in the liver, granulation tissue with fibroplasia) or antigenic stimulation (lymphoid hyperplasia). Aspiration of hyperplastic lesions may result in a higher than expected cellularity and cells may display some mild criteria of malignancy, such as a mildly increased N:C ratio, darker blue cytoplasm, slightly more prominent nucleoli or finer chromatin than normal. The latter change can be referred to as “atypia” or “dysplasia”, which are terms used inter-changeably (see below).

Dysplasia, or disordered growth, is most often seen in epithelial tissue and results in loss of uniformity of the individual cells and disordered architectural arrangement of the cells. In human medicine, the term is applied mostly to preneoplastic or neoplastic conditions and is commonly used with myeloid hematopoietic neoplasms, e.g. myelodysplastic syndrome. Dysplasia can also refer to developmental abnormalities in tissues, e.g. renal dysplasia. With cytologic assessment of smears, we use the term dysplasia to indicate abnormal features in cells, such nuclear to cytoplasmic asynchrony, increased cytoplasmic basophilia, anisokaryosis and anisocytosis, typically associated with neoplastic conditions, although hematopoietic cells can have features of dysplasia with non-neoplastic conditions, such as drug therapy. The term dysplasia is often used inter-changeably with that of “atypia”, which adds to confusion. However, some pathologists use the term atypia for features that encompass reactive changes, e.g. in response to irritation or inflammation, and neoplasms. Cytologic atypia can be quite marked in reactive conditions; mesothelial cell hyperplasia in idiopathic pericardial effusions is prime example of this atypia in the absence of detectable neoplasia. Mesothelial cells in idiopathic pericardial effusions can be markedly atypical, showing multinucleation (including trinucleation) and marked anisokaryosis and anisocytosis.

Cytologically, a hyperplastic process can be difficult to distinguish from a benign neoplastic process and if there is substantial atypia in cells within such aspirates, one must exercise caution as to not interpret the atypia as malignant neoplasia (reactive mesothelial cells are particularly difficult to distinguish from a carcinoma). Histopathologic assessment of the tissue should always be done if there is any doubt.

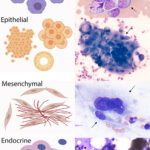

Neoplasia

Neoplasia is suspected when there is a population of tissue cells in an aspirate that are not expected to be there, there is a mass lesion consisting of cells that are in excess for the aspirated site (e.g. too many sebaceous cells in a skin lesion) or the tissue cells are showing cytologic criteria of malignancy. Neoplasms are further divided into four general tumor categories: Epithelial, mesenchymal, discrete (round) cell and endocrine/neuroendocrine (naked nuclei) neoplasms, based on their cytologic features and pattern of arrangement.

Epithelial neoplasms

Epithelial tumors are cohesive and form clusters or sheets. They can show trabecular, circular to papilliform arrangements. Acini may be seen in cells that produce secretory product. Examples of epithelial tumors include perianal gland adenoma, transitional cell carcinoma, biliary carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma. Epithelial cells generally have the following features:

- Large, round to polygonal cells

- Distinct cell borders

- Tightly adherent to each other

- Round to oval nuclei that can be basilar in columnar cells or eccentric in other cell shapes

Epithelial tumors can be benign (adenoma) or malignant (carcinoma). Benign versions consist of well-differentiated cells that can be difficult to distinguish from normal tissue (unless in excess for the aspirated site) or hyperplastic lesions (which may require evaluation of tissue architecture, e.g. normal architecture and arrangement around ducts would indicate hyperplasia versus neoplasia for skin adnexal tumors). Malignant epithelial cells usually demonstrate cytologic criteria of malignancy particularly as they become more aggressive or advanced. However, some carcinomas (e.g. the rare perianal carcinomas) do not always show features of malignancy but behave in a malignant fashion. As carcinomas become less differentiated they lose some of these features and often become less cohesive, mimicking mesenchymal cells. Indeed, epithelial tumors undergo epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition when they are metastasizing so spindled cells within an epithelial tumor may represent the tumor undergoing EMT or reactive fibroplasia (e.g. schirrous response, which is seen with certain epithelial tumors such as intestinal tumors). In the more anaplastic tumors, immunohistochemical staining for cytokeratin can be necessary to confirm an epithelial origin. We can often determine the type of epithelial tumor on cytology, particularly if the cell of origin has specific features (e.g. perianal tumors have a “hepatoid” appearance; exocrine pancreatic carcinomas have faint pink cytoplasmic granules) or the tumor cells are showing features of differentiation (e.g. squamous cell carcinoma). In many cases, the type of tumor may be based on the aspirated site, e.g. mammary gland, along with cytologic features (i.e. we use the history to help determine what the lesion or tumor is).

Mesenchymal neoplasms

Mesenchymal neoplasms carry features of their embryonic tissue of origin, the mesenchyme. The cells are generally individualized and spindled in shape. They can be seen in aggregates (not clusters), often held together by extracellular matrix. They do not typically demonstrate cell-to-cell adhesion. Due to increased matrix production, there are some mesenchymal tumors (e.g. fibroma) that do not exfoliate well and aspirates may be of low cellularity making a definitive cytologic diagnosis difficult. Examples include myxoma, fibrosarcoma, osteosarcoma, melanoma and hemangiosarcoma. Mesenchymal tumors generally have the following features:

- Spindle, oval or stellate-shaped cells

- Indistinct cell borders, that taper into the background

- Round to oval to elongate nuclei that are usually centrally located

- Cells are scattered individually or in aggregates, usually within matrix.

- Less cellular than the other tumors due to matrix

- Matrix can be present in the background as well as within aggregates

As for epithelial tumors, mesenchymal tumors can be benign (“..oma”) or malignant (“sarcoma”). Some types of mesenchymal tumors, e.g. soft tissue sarcomas, are called sarcomas, even though they do not metastasize quickly. They are, however, locally invasive. There are also certain types of mesenchymal tumors that mimic epithelial tumors, showing cell-to-cell adhesion, including melanoma and epithelioid variants of hemangiosarcoma. It can be quite difficult to differentiate between a mesenchymal tumor and reactive fibroblasts on cytologic features alone, because the latter can have quite large nuclei and prominent nucleoli (they also display moderate to occasionally marked anisokaryosis and anisocytosis). This is particularly a problem in bloody or poorly cellular specimens. Several variants of mesenchymal tumors can be diagnosed with certainty on cytology if they have characteristic cellular features (e.g. crown-like cells in soft tissue sarcoma, melanin in melanocytic tumors) or characteristic matrix (e.g. osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma). We can also use site to narrow down the differential diagnostic list. For example, a gastrointestinal stromal cell tumor or smooth muscle tumor (leiomyoma, leiomyosarcoma) would be suspected for a mesenchymal tumor arising in the intestine. However, there are many mesenchymal tumors in which a definitive determination of tumor type cannot be provided, even when we know the aspirated site.

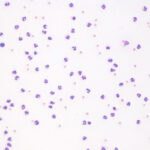

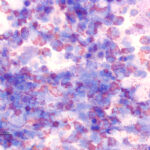

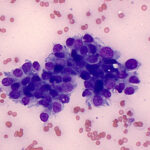

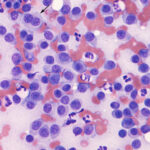

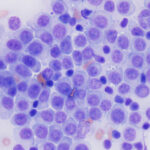

Discrete (round) cell neoplasms

Discrete or round cell tumors often are of hematopoietic origin (lymphoma, histiocytic, mast cell tumor) and as the term suggests, consists of individualized round cells. Cells tend to exfoliate readily and aspirates are often of high cellularity. We can use morphologic features of the cells, including the presence or absence of granules and cytoplasmic and nuclear features, to determine the type of round cell tumor.

Mast cell tumor

- These are readily recognized by the presence of purple cytoplasmic granules.

- They also have round eccentric nuclei with smooth chromatin. The nuclei can be hard to see as the granules soak up the stain

- The degree of granularity varies between tumors. Granules may be harder to discern with water-based stains, such as Rapid stains, particularly in the less well-granulated tumors.

- Low grade tumors are typically well-granulated. Higher grade tumors can be poorly or well-granulated and nuclear criteria of malignancy (nuclear atypia, binucleation, large nuclei, mitotic figures) are more reliable than granularity for determining the grade of mast cell tumors on cytology. Tumor grading for dermal (not subcutaneous) mast cell tumors in dogs is best done by histopathology.

Histiocytoma: Cell of origin is the epidermal Langerhans cell. These may not be tumors per se as they regress without treatment due to a cytotoxic T cell immune response. They can be single (usually are) or multiple

- Round to oval with variably distinct cytoplasmic borders.

- Moderate to abundant amounts of clear to light blue cytoplasm

- Nuclei are eccentric and round to oval to indented

- Nuclei have finely stippled chromatin and nucleoli are not apparent

- Cells are often found dispersed within a moderately blue background

- Minimal cellular atypia, uniform cell size and morphology – they have a bland appearance

- Regressing tumors are associated with increased numbers of small lymphocytes (tumor infiltrating cytotoxic T-cells)

- Note: Histiocytomas generally consist of very bland, minimally atypical cells. If a high degree of cellular atypia (numerous criteria of malignancy) are found and a histiocytic lineage is still suspected, histiocytic sarcoma should be considered a differential diagnosis.

- The main differential diagnosis is an extramedullary plasmacytoma. Lightly stippled chromatin, abundant light blue cytoplasm, indented nuclei and the blue background are used to distinguish between these lesions (not all features may be present in every tumor).

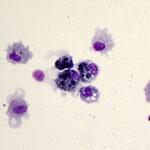

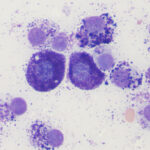

Plasmacytoma: These arise from plasma cells, which form tumors (usually solitary) in extramedullary sites, such as the skin (digit, ears, mouth) in dogs.

- Round to slightly oval cells

- Distinct cell borders

- Variable amounts of blue cytoplasm (often deep blue), some have perinuclear clear zones

- Nuclei are round, occasionally oval, and eccentric

- Nuclei have clumped chromatin and nucleoli are not apparent

- More atypia (anisocytosis and anisokaryosis) than histiocytic tumors

- Binucleation and, occasional, multinucleation is common. Multinucleated cells may show marked intracellular anisokaryosis

- Amyloid may be present in skin tumors.

- The main differential diagnoses are a histiocytoma or plasmacytoid variants of lymphoma. Compared to a histiocytoma, the cells have more distinct boundaries, darker cytoplasm, rounder nuclei (even in multinucleated cells) and clumpier chromatin. They may have perinuclear clear zones. With plasmacytoid variants of lymphoma, cells with higher nuclear to cytoplasmic ratios resembling lymphocytes are expected to be present.

Lymphoma: There are multiple forms of cutaneous lymphoma, including inflammatory, epitheliotropic and non-epitheliotropic forms. In the skin, lymphoma can consist of solitary to multiple nodules, plaques or ulcerative/exfoliative lesions. It can be pruritic. Lymphoma, as we know, also arises in other sites. They are usually of T or B cell origin. Lymphomas of natural killer cell origin are quite rare. Lymphoma is most easily recognized when it consists of large cells or cells that are not expected in inflammatory lesions, such as many granular lymphocytes. It is far harder to recognize when the cells are intermediate to small, however the lack of other immune cells (plasma cells) or inflammatory cells can lead to a suspected diagnosis of lymphoma. Lymphoid cells have the highest nuclear to cytoplasmic ratios of all the round cells. They can rupture easily and one can see cytoplasmic fragments (“lymphoglandular” bodies) in the background, which can be a helpful but not definitive finding. The main differential diagnoses for cutaneous lymphoma are inflammatory or immune-mediated conditions or localized antigenic stimulation, e.g. pseudolymphoma secondary to an insect bite. There are histiocytic variants, which have more abundant cytoplasm and can mimic a histiocytoma. Ultimately, the diagnosis of cutaneous lymphoma often requires biopsy with immunohistochemical staining to confirm a T (CD3) or B (e.g. Pax-5 or CD20) origin for the tumor cells.

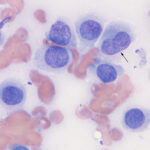

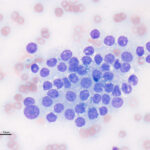

Transmissible venereal tumor: This sexually transmitted tumor is thought to be of histiocytic origin. It is mostly seen in warmer cell climates and is often around the mouth or genital region, but can be seen in other sites.

- Monomorphic population of round cells

- Medium to large round nucleus that is eccentric or central

- Nuclear chromatin is clumped and mitotic figures are common

- Can see binucleation or multinucleation as well as nucleoli

- The cytoplasm is characteristic: Abundant light blue to gray with moderate to many discrete margined vacuoles

- Can have infiltrates of small lymphocytes

Endocrine/neuroendocrine tumors

These tumors have a characteristic appearance, forming packets of cells. Cells often exfoliate in large numbers but are fragile and aspirates contain many bare nuclei from ruptured cells, hence some people call them “naked nuclei” neoplasms. They are of secretory epithelial (producing hormones, e.g. thyroid tumors) or neuroectodermal origin, with the latter secreting neurotransmitters, such as epinephrine in phaechromocytomas. Many of these tumors have quite uniform or bland cytologic features, but show aggressive malignant behavior (e.g. thyroid carcinomas in dogs), therefore cytologic criteria of malignancy are unreliable and we go by the known biologic behavior of the tumors. The type of endocrine or neuroendocrine tumor is generally determined by site, e.g. a cervical neck mass could be thyroid or parathyroid in origin, with the former being more common. In some types of tumors, we can be more definitive, for example thyroid follicular tumors can contain tyrosine granules (blue green pigment) in the cytoplasm.

- Round to polygonal cells found in cohesive packets or small sheets

- Nuclei are round to oval and central to eccentric

- Nuclear chromatin is fine to smooth

- Indistinct cell borders

|

Epithelial |

Mesenchymal |

Discrete “round” cell |

Endocrine/neuroendocrine |

|

|

Typical cellularity of aspirates |

High | Low to moderate (May be high in a few specific tumors, e.g. soft tissue sarcoma) |

High | High, may have large numbers of individualized free nuclei from ruptured cells (“naked nuclei”) |

|

Cell Associations |

Clusters (adherent); can see acinar formation if secretory | Individual cells, or in some non-cohesive aggregates | Individual cells; may form aggregate-like arrangements in thicker aspirates | Clusters (adherent); can see acinar formations in endocrine tumors |

|

Cell Shapes |

Variable: Often polygonal, columnar, or cuboidal | Spindled to stellate to rarely round (histiocytic sarcoma) | Round (ish) | Generally round or cuboidal |

|

Cell Size |

Medium to large | Medium | Small to medium; large with large cell lymphoma | Small to medium |

|

Cell Borders |

Distinct in most tumors | Often indistinct | Distinct | Indistinct |

|

Nuclear Shape |

Round to oval | Oval to elongated to round (e.g. soft tissue sarcoma) | Round, sometimes indented (histiocytic tumors) | Round |

|

Other Characteristics |

Can see features of differentiation (e.g hepatoid cells, squamous cells) | Some tumor types may be associated with characteristic extracellular matrix (e.g. chondrosarcoma) | Cytoplasmic purple granules in mast cell tumors may occasionally stain poorly with Diff-Quik | Tend to lack cytologic features of malignancy regardless of biologic behavior |

|

Examples of tumors |

Benign: Adenomas Malignant: Carcinomas |

Benign:“-omas”, e.g. fibromas Malignant or invasive: Sarcomas |

Lymphoma Plasmacytoma Mast cell tumor Histiocytoma Transmissable veneral tumor |

Insulinoma Thyroid tumors Apocrine anal sac adenocarcinoma Phaechromocytoma Paraganglioma |