Interpretation

Mixed neutrophilic histiocytic (pyogranulomatous) inflammation due to a mycelial fungal infection.

Explanation

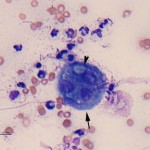

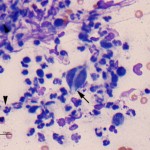

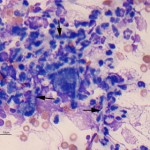

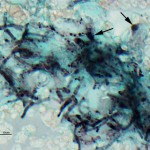

The cytology smears are highly cellular consisting of mostly non-degenerate neutrophils, moderate numbers of macrophages, and few lymphocytes (Figure 1b, question 1). A moderate amount of blood is present in the background of these smears. Vacuolated macrophages and several multinucleated macrophages are present with some evidence of erythrophagia (not shown), supporting hemorrhage into the lesion. Numerous pale, nonpigmented linear fungal hyphae are present, some of which were phagocytized by macrophages (Figures 2b and 3, question 2). Dense mats of the hyphae were observed. A Gomori’s Methenamine Silver (GMS) stain was done to highlight the fungal elements in the sample (Figure 4). The hyphae were septate, branching (45 to 90°), and often parallel-sided, however numerous hyphae had bulbous non-parallel sides (Figures 1b and 4). Several appeared to be arising from oval to round encapsulated yeast forms (Figure 4). No bacteria or other infectious agents are seen. The results indicated a mixed neutrophilic histiocytic (pyogranulomatous) inflammatory response due to a mycotic infection (questions 1 and 2), with intralesional hemorrhage. The nature of the fungus could not be determined from the aspirate, however aspergillosis and penicilliosis were considered unlikely due to the non-parallel sides and yeast-like structures. Mycelial forms of Blastomyces dermatitidis and other fungal organisms were considered possible causative agents.

|

|

|

|

Additional testing

A lymph node aspirate from the iliac and prescapular nodes demonstrated a similar mixed inflammatory response, with fungal hyphae, indicating a systemic infection. This was likely the cause of the systemic inflammatory response and the associated hematologic and biochemical changes, all of which could be attributed to inflammation (question 3). Fungal serology for Blastomyces, Histoplasma, Coccidioides, Aspergillus, and Cryptococcus was negative. Aerobic and anaerobic bacterial culture on the femur were negative. No Blastomyces organisms were cultured from the urine. Penicillium sp were cultured from the femoral mass but the organism was not speciated further.

Discussion

Disseminated fungal infection occurs most frequently with encapsulated yeast, such as Blastomyces dermatitidis, Cryptococcus gattii and neoformans, Coccidioides immitis and Histoplasma capsulatum, while systemic infection caused by mycelial fungi is uncommon in dogs. The most common isolate from disseminated mycelial fungal infection is Aspergillus (terreus or deflectus), although other organisms, including Penicillium, Geomyces (formerly Chrysosporium), Paecilomyces, and Pseudallescheria have been isolated from individual dogs1,2. Hyphating and pseudohyphating forms of Blastomyces dermatitidis (the mycelial form is called Ajellomyces dermatitidis)3 and Candida spp.4 have also been identified in dogs, so these yeast should be considered as a cause for a systemic or localized mycoses of (pseudo) hyphating fungi. Hyphating fungi are ubiquitious in the environment. Infection is thought to be acquired via ingestion of contaminated soil or water, contamination of skin wounds, or inhalation of spores. Localized cutaneous or nasal infection can occur5, but the reason for dissemination is unknown. Most dogs with systemic mycelial mycoses are thought to be concurrently immunosuppressed (e.g. prior chemotherapy, corticosteroid treatment, diabetes mellitus), although evidence of immunosuppression may be absent in some dogs. German Shepherd dogs are predisposed to systemic fungal infections, particularly young female dogs6, which is thought to be a consequence of IgA deficiency in this breed7.

Clinical signs of dogs with systemic fungal infection include anorexia, lethargy and weight loss and pyrexia1,6. Lymphadenopathy of multiple nodes (internal and external) is frequently observed. However, aspiration reveals pyogranulomatous inflammation and, hopefully, the causative organism2,6. Infection with Aspergillus, Geomyces and Penicillium can result in osteomyelitis or discospondylitis and affected animals can present with neck or back pain, and paresis or paralysis1,2,6,8,9. Aspergillosis also frequently infects the kidney and the organism can be cultured from the urine in systemic infections1,6. Clinical pathologic testing usually reveals evidence of inflammation (hyperglobulinemia, leukocytosis)2,6, with hypercalcemia being reported in cases of aspergillosis (likely secondary to granulomatous inflammation)6. Interestingly, our case had a similar presentation to a 7 year old spayed female Collie infected with Penicillium verruculosum9. The latter dog presented with left forelimb lameness of 1.5 years. Diagnostic imaging revealed an osteolytic lesion in the proximal femur, with a concurrent periosteal reaction, and internal and external lymphadenopathy, as seen in our case. A bone marrow aspirate in the Collie revealed fungal elements within phagocytized macrophages and fungi were identified in lymph node aspirates (which also had neutrophilic and histiocytic inflammation). The fungi were cultured and speciated by the appearance of the conidiophores and polymerase chain reaction confirmed the fungus was a Penicillium9.

Since fungal hyphae can be difficult to detect in Romanowsky-stained smears, such as the Wright’s stain used in our laboratory, (they are frequently non-staining and often immersed within necrotic cellular debris), GMS staining is worthwhile on tissue aspirates to help confirm a diagnosis. This was not needed in this current case, because fungal hyphae were readily observed in the Wright’s stain, however the GMS helped more clearly define the structure of the fungal hyphae. Although the fungal hyphae were mostly parallel sided, bulbous and non-parallel variants were seen, along with yeast-like structures. The latter findings are atypical for Penicillium or Aspergillus spp. but have been reported in a dog infected with Geomyces2. Thus, even though Penicillium was cultured, it could have been a contaminant in this case and infection with another organism (potentially Geomyces) is still considered possible (and could have been potentially confirmed by speciation of organisms from tissue sections). Unfortunately, conidia were not identified in the aspirates, which would have helped with speciation.

Dogs with systemic mycelial mycosis are treated with antifungal agents, including amphotericin B and itraconazole1,2,6,9. Long term clinical remission has been documented in some cases1,2,6, however the prognosis, particularly in dogs with systemic illness, is still considered poor.

Further information and follow-up

Due to poor prognosis of this condition despite long term treatment, the owner elected for euthanasia.

References

- Watt PR et al. 1995. Disseminated opportunistic fungal infection in dogs – 10 cases (1982-1990). J Am Vet Med Assoc 207: 67-70.

- Erne JB et al. 2007. Systemic infection with Geomyces organisms in a dog with lytic bone lesions. J Am Vet Med Assoc 230: 537-540.

- Bulla C and Thomas JS. 2009. What is your diagnosis? Subcutaneous mass fluid from a febrile dog. Vet Clin Pathol 38: 403-405.

- Rogers CL et al. 2009. Disseminated candidiasis secondary to fungal and bacterial peritonitis in a young dog. J Vet Emerg Crit Care 19: 193-198.

- Harvey CE. 1984. Nasal aspergillosis and penicilliosis in dogs: results of treatment with thiabendazole. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 184: 48-50.

- Schultz RM et al. 2008. Clinicopathologic and diagnostic imaging characteristics of systemic aspergillosis in 30 dogs. J Vet Intern Med 22: 851-859.

- Day MJ et al. 1985. Immunologic study of systemic aspergillosis in German Shepherd dogs. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 9: 335-347.

- Wigney DI et al. 1990. Osteomyelitis associated with Penicillium verruculosum in a German Shepherd dog. J Small Animal Pract. 31: 449-552.

- Miyakawa K et al. 2011. Pathology in practice. Penicilliosis. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 238: 51-53.