Interpretation

Right lateral distal hind leg mass and left medial hind leg mass: Sarcoma, likely cutaneous or dermal hemangiosarcoma.

Right medial hind leg mass: Non-diagnostic.

Abdominal mass: Mesenchymal tumor, suspect myxosarcoma, with secondary histiocytic inflammation, likely involving mesenteric fat and hemorrhage.

Explanation

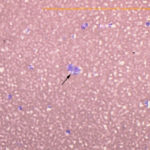

Hind leg masses: The smears from the right lateral distal (Figures 1 and 5) and left medial hind leg were similar and consisted of blood with a few aggregates and individualized spindle cells (Question 1). The latter cells had oval nuclei with stippled chromatin and small amounts of light blue cytoplasm with indistinct boundaries. The cells displayed mild anisokaryosis and anisocytosis in smears from the aspirate of the left hind leg mass, but displayed more anisokaryosis (moderate overall) in the smears from the aspirate of the right lateral hind leg mass. Aspirates from the right medial hind leg mass lacked tissue cells and only contained blood. Although cellularity was low, the morphologic features of the cells in the masses from the right lateral and left medial hind legs, with the provided history, were compatible with hemangiosarcoma (Question 2).

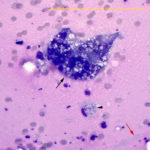

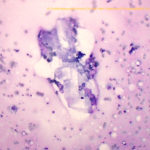

Abdominal mass: The smears consisted of blood in a dense purple mucinous background with “windrowing” (lining up) of leukocytes and red blood cells (Figures 2 and 6). There were increased macrophages with several multinucleated giant cells, including Langhans variants (Figures 6, 7). There were also numerous spindle cells, which were mostly associated with fibrillar pink light mucinous matrix (Figures 3-4). The spindle cells had central oval nuclei with single nucleoli, relatively coarse to clumped chromatin and moderate amounts of light to medium blue cytoplasm that tapered away from both poles of the nucleus. The cells displayed mild anisokaryosis and anisocytosis overall, but individual cells had larger nuclei. Macrophages contained pink granular phagocytic material in their cytoplasm (possibly mucin) and some were erythrophagocytic. Many contained moderate numbers of lipid droplets in their cytoplasm (suggesting phagocytosis of mesenteric fat). Cholesterol crystals were seen on scanning and indicated breakdown of cholesterol-rich membranes (Figure 8). The numerous spindle cells in the mass from the abdomen indicated a mesenchymal tumor and, with the large amounts of mucinous matrix, a myxoid-producing tumor, such as a myxosarcoma (based on high cellularity and variation in the spindle cells) was favored (Question 2). Other sarcomas with areas of myxoid change could not be ruled out. The tumor was not thought to be related in any way to the cutaneous hemangiosarcomas (i.e., a “twofer”, Question 3).

Additional Diagnostic Testing

The dog was taken to surgery for removal of the abdominal mass and biopsy of multiple skin masses. At surgery, the abdominal mass was a mural lesion within the right bladder wall. This was resected. Histopathologic evaluation of the skin biopsy confirmed dermal hemangiosarcoma in all sites (3 right medial leg masses, 2 left medial leg masses, 1 right lateral leg mass), except for the right lateral hind leg mass, which was a subcutaneous hemangiosarcoma. Anisocytosis and anisokaryosis in all sites was mild. Initial histopathologic evaluation of the mass yielded a diagnosis of mural spindle cell sarcoma, suspect myxofibrosarcoma with gastrointestinal stromal cell tumor (GIST) as a differential diagnosis. The tumor appeared to have narrow margins but was completely resected. There was 1 mitotic figure per 10 high power fields (low rate) and the tumor cells were relatively uniform in appearance and imbedded in an abundant myxomatous matrix with thin fibrils of collagen. Subsequent immunostaining for markers expressed by GISTs (c-kit) and leiomyomosarcomas (smooth muscle actin) was negative. The final diagnosis was a myxosarcoma or myxofibrosarcoma. The dog was treated for the hemangiosarcomas with metronomic therapy of chlorambucil and carprofen.

Discussion

Hemangiosarcomas are tumors of blood vessels that can arise in any site, but typically occur in the spleen and atria. Cutaneous hemangiosarcomas comprise less than 20% of cases and, in one study of 212 cases of hemangioma and hemangiosarcoma, were less common than their more benign counterparts, hemangiomas.1 Cutaneous hemangiosarcomas were more common in the dermis (around 90%) than subcutaneous tissue and both benign and malignant tumors were seen more frequently in dogs with light skin coats containing shorter hairs.1 Both tumor types are often located on the ventrum (haired and unhaired skin), but can also be seen on other sites, including the head, trunk and legs. Solar elastosis was seen in the adjacent skin in many of the tumors, leading to the theory that they are induced by ultraviolet light exposure.1 The tumors can be single or multiple and can recur after tumor excision.1-2 They can metastasize, although survival is longer than corresponding primary splenic tumors.1-2

Due to their frequent high vascularity, aspirates of hemangiosarcomas are not always diagnostic, consisting largely of blood with blood-associated leukocytes. However, we frequently do get lucky and aspirates can contain low to moderate numbers of spindle cells. If the spindle cells largely lack cytologic criteria of malignancy, we are left with a diagnostic conundrum: Are the spindle cells reactive fibroblasts or tumor cells, such as from a benign mesenchymal tumor (including a hemangioma) or a more malignant version? In these situations, clinical pathologists will often “fence sit” and indicate both possibilities and recommend surgical removal and histopathology for differentiation. If there is concurrent necrosis, if the spindle cells do not have “typical features” of reactive fibroblasts (a subjective opinion) or are showing some cytologic criteria of malignancy, or if there is a corroborating history, such as in this case, a clinical pathologist may lean towards a diagnosis of cancer. If the cells are showing obvious criteria of malignancy, even if in low number (such as “in your face” gigantic nuclei or nucleoli), a diagnosis of cancer can be provided in these blood/spindle cell aspirates. As for any aspirate, cytologic yield is never 100%, but considering the low cost and morbidity of the technique, aspiration of such lesions is always worthwhile. Some hemangiosarcomas have unique features, such as the epithelioid variants, which can be mis-diagnosed as carcinomas.3-4 Others can have foci of extramedullary hematopoiesis,3,5 which would be unusual to see in an area of reactive fibroplasia. Increased neutrophils have been associated with some of these tumors, attributed to increased margination3 or tumor-associated inflammation, particularly if there are areas of necrosis.

Myxosarcomas are uncommon tumors in dogs and have been reported in the skin, heart, orbit, bone, and spleen.6-10 They consist of mesenchymal cells in an abundant mucin-rich matrix, which stains positive for mucopolysaccharides (simple non-sulfated mucin acids) with Alcian blue at a pH of 2.5, that is resistant to hyaluronidase digestion.6 However, other sarcomas, including liposarcomas, soft tissue sarcomas (e.g. peripheral nerve sheath tumors), and fibrosarcomas, can also produce mucin.6,11 Since some of these tumors lack specific markers of differentiation (liposarcoma, fibrosarcoma), distinguishing between these different neoplasms relies on degree and staining characteristics of matrix, pattern of arrangement of the spindle cells and the opinion of the pathologist. Myxosarcomas are also difficult to differentiate from their benign counterparts. This is generally accomplished by assessing the degree of nuclear pleomorphism and size variation, which is greater with myxosarcomas, and identifying aberrant mitotic figures, which are not expected in benign tumors.6 Despite their malignant designation, these tumors do not metastasize readily and are largely considered to be low grade.

This case was unusual because of the presence of two different types (one likely multiple) of mesenchymal tumors in the dog. In addition, the abdominal mass, which appeared to arise from the bladder wall, was initially thought to be of muscle (leiomyoma/leiomyosarcoma) or interstitial cell of Cajal (pacemaker of intestinal smooth muscle, GIST) origin. There are reports of myxoid-containing GISTs,12 however the tumor in this dog was negative for c-kit, a recognized marker of these tumors.13 The abdominal mass was not believed to be a metastatic site for the suspected cutaneous hemangiosarcomas, primarily because of the abundant mucinous matrix. Although matrix can be seen rarely in aspirates of hemangiosarcoma (both extracellularly and presumably within cells),3 none of the aspirates from the skin masses contained matrix and the large amount of mucinous matrix is not a feature of these vascular tumors.

References

- Hargis AM, Ihrke PJ, Spangler WL, et al A retrospective clinicopathologic study of 212 dogs with cutaneous hemangiomas and hemangiosarcomas. Vet Pathol 1992; 29:316-328. PMID: 1514218

- Ward H, Fox LE, Calderwood-Mays MB, et al. Cutaneous hemangiosarcoma in 25 dogs: a retrospective study. Journal of veterinary internal medicine / American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine 1994;8:345–8. PMID: 7837111

- Bertazzolo W, Dell’Orco M, Bonfanti U, et al. Canine angiosarcoma: cytologic, histologic, and immunohistochemical correlations. Veterinary clinical pathology / American Society for Veterinary Clinical Pathology 2005;34:28–34. PMID: 15732014.

- Warren AL, Summers BA. Epithelioid variant of hemangioma and hemangiosarcoma in the dog, horse, and cow. Vet Pathol 2007;44:15–24. PMID 17197620

- Dunbar MD, Conway JA. What is your diagnosis? Cytologic findings from a subcutaneous nodule over the left epaxial musculature in a dog. Veterinary clinical pathology / American Society for Veterinary Clinical Pathology 2012;41:295–6. PMID: 22486411

- Gross T. Ihrke PJ, Walder EJ, Affolter VK. Skin Diseases of the dog and cat, 2nd ed. Blackwell Science Ltd, Oxford, UK. pp: 728-30.

- Riegel CM, Stockham SL, Patton KM, et al. What is your diagnosis? Muculent pleural effusion from a dog. Veterinary clinical pathology / American Society for Veterinary Clinical Pathology 2008;37:353–6. PMID: 18761532

- Khachatryan AR, Wills TB, Potter KA. What is your diagnosis? Vertebral mass in a dog. Veterinary clinical pathology / American Society for Veterinary Clinical Pathology 2009;38:257–60. PMID: 19490569

- Campos CB, Nunes FC, Gamba CO, et al. Canine low-grade intra-orbital myxosarcoma: case report. Vet Ophthalmol 2015;18:251–253. PMID: 24837165

- Spangler WL, Culbertson MR, Kass PH. Primary mesenchymal (nonangiomatous/nonlymphomatous) neoplasms occurring in the canine spleen: anatomic classification, immunohistochemistry, and mitotic activity correlated with patient survival. Vet Pathol 1994;31:37–47. PMID 8140724

- Plumlee QD, Hernandez AM, Clark SD, et al. High-Grade Myxoid Liposarcoma (Round Cell Variant) in a Dog. J Comp Pathol 2016;155:305–309. PMID: 27665042

- Li B, Zhang Q-F, Han Y-N, et al. Plexiform myxoid gastrointestinal stromal tumor: a potential diagnostic pitfall in pathological findings. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2015;8:13613–13618. PMID: 26722584

- Hayes S, Yuzbasiyan-Gurkan V, Gregory-Bryson E, et al. Classification of canine nonangiogenic, nonlymphogenic, gastrointestinal sarcomas based on microscopic, immunohistochemical, and molecular characteristics. Vet Pathol 2013;50:779–788. PMID: 23456969

Authored by: T Stokol and Dr. Lindsay Thalheim.