Interpretation

Extravascular hemolytic anemia due to Mycoplasma haemocanis (Question 1).

Explanation

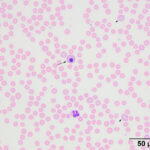

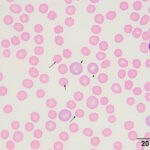

The moderate anemia was mildly regenerative, based on the absolute reticulocyte count. Polychromatophils were seen in the blood smear, supporting regeneration (Figures 1-2). The high numbers of nucleated red blood cells could be attributed to release from the bone marrow or lack of a spleen. The main finding on the blood smear was the presence of numerous epicellular parasites forming rings, rods, and short chains across the surface of the red blood cells (RBC), frequently indenting or distorting the RBC membrane (Figures 1-2). The morphologic features of the organism are compatible with Mycoplasma haemocanis. Platelets were judged low on the smear and a few platelets were also large (not shown), supporting a regenerative response to and a peripheral cause for the thrombocytopenia.

|

|

The initial anemia post surgery was attributed to blood loss during surgery, however the dog was mildly anemic 2 years prior. The 40% hematocrit at that time could be normal for this dog or reflect underlying inflammatory or chronic disease that did not manifest with other clinical or clinical pathologic abnormalities. The dog either acquired the Mycoplasma infection from one of the blood transfusions during surgery or was a subclinical carrier of Mycoplasma (potentially from prior blood transfusions associated with prevention or treatment of vWD-associated hemorrhage), with splenectomy helping to precipitate bacteremia and the clinical signs (Question 2). The lymphopenia was attributed to concurrent stress (on each blood sampling occasion).

Follow up

The dog was treated with doxycycline. A follow-up hemogram performed 3 weeks later showed a mildly decreased HCT (39%), a rebound thrombocytosis (802 x 103/uL) and a normal leukogram.

Discussion

Mycoplasma haemocanis is a small pleomorphic bacterium that parasitizes RBCs and is part of the genus Mycoplasma. The organism is enclosed by a single membrane and lacks a cell wall. It is found within indentations in the RBC membrane on electron microscopy and forms circles (0.2-1.0 um), rings (1-3 um), rods (up to 1 um) or chains, which frequently extend cross the surface of the RBC membrane, on light microscopy.1 The bacterium was formerly known as Bartonella and Haemobartonella canis. It was first recognized in 1928 in an anemic dog2 and is now found worldwide with varying prevalence rates.3–5 Two genetic isolates based on 16S gene sequencing have been recognized; Mycoplasma haemocanis and Candidatus Mycoplasma haemotoparvum, with the latter showing higher sequence morphology to the feline isolate, Candidatus Mycoplasma haemominutum.4,6,7 Nanopore-based sequencing has identified a potentially novel Mycoplasma species in the blood of dogs.8 In two studies of 460 and 850 dogs in Europe, a 3-40% prevalence of infection was found, with dual infections of both Mycoplasma species in a low percentage of dogs (the dominant isolate varied between the studies).3,4 Risk factors for infection in one of these studies were young age, kenneling, concurrent mange infection (suggesting immunosuppression), and crossbreeding.3 In contrast, <1% of 6150 blood units from 1914 blood donor dogs in Canada were PCR positive for Mycoplasma haemocanis or haematoparvum.5 Dogs with Mycoplasma haemocanis can be co-infected with other tick-borne bacteria, including Ehrlichia canis and Anaplasma platys.8,9

The organism is transmitted via administration of blood products10–13 or ticks, such as Rhipicephalus sanguineus,14 with evidence of vertical transmission.9 Many infected dogs are latently infected and not anemic.3,10,15 They only develop anemia when they are splenectomized (as in this case), immunosuppressed, or co-infected with other bacteria or viruses.10–13,15–18 Exposure of splenectomized dogs to infected ticks or blood results in parasitemia within 4 to 22 days, which can be cyclical thereafter.10,13,14 Acute severe infections can result in death but the anemia can be mild and take several weeks to develop.10,12,13,15 A slowly developing anemia presumably occurred in this case considering the 6 week time frame after surgery and splenectomy and the detection of a moderate anemia, which was unchanged compared to the post-surgical value. The anemia is typically due to extravascular hemolysis. A Coombs’-positive hemolytic anemia with spherocytosis has been reported in a dog with concurrent Mycoplasma haemocanis infection.19 However, Mycoplasma haemocanis is not a recognized cause of associative immune-mediated hemolytic anemia,20,21 with a low level of evidence.21 A thrombocytopenia can be concurrently seen in some dogs,15,18 as occurred in this case. The mechanism is unclear but it may be due to immune-mediated destruction or complement-mediated activation. Icterus or hyperbilirubinemia is typically not seen in anemic animals10,13,18 and was not evident in this case.

Mycoplasma haemocanis infection is usually treated with tetracylines; the organism can rapidly disappear from blood within a few days of treatment.17,18 The organism may persist in a latent form despite successful resolution of hematologic abnormalities and clinical signs with treatment. Relapses may occur.18

Author: T Stokol.

References

- Venable JH, Ewing SA. Fine-structure of Haemobartonella canis (Rickettsiales: Bartonellacea) and its relation to the host erythrocyte. J Parasitol. 1968 Apr;54(2):259–68.

- Kiküth W. Uber einen neuen anamieerreger, Bartonella canis nov. sp. Klin Wchnschr. 1928;7:1729–30.

- Novacco M, Meli ML, Gentilini F, Marsilio F, Ceci C, Pennisi MG, et al. Prevalence and geographical distribution of canine hemotropic mycoplasma infections in Mediterranean countries and analysis of risk factors for infection. Vet Microbiol. 2010 May 19;142(3–4):276–84.

- Kenny MJ, Shaw SE, Beugnet F, Tasker S. Demonstration of two distinct hemotropic mycoplasmas in French dogs. J Clin Microbiol. 2004 Nov;42(11):5397–9.

- Nury C, Blais MC, Arsenault J. Risk of transmittable blood-borne pathogens in blood units from blood donor dogs in Canada. J Vet Intern Med. 2021 May;35(3):1316–24.

- Sykes JE, Bailiff NL, Ball LM, Foreman O, George JW, Fry MM. Identification of a novel hemotropic mycoplasma in a splenectomized dog with hemic neoplasia. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2004 Jun 15;224:1946–51, 1930–1.

- Barker EN, Tasker S, Day MJ, Warman SM, Woolley K, Birtles R, et al. Development and use of real-time PCR to detect and quantify Mycoplasma haemocanis and “Candidatus Mycoplasma haematoparvum” in dogs. Vet Microbiol. 2010 Jan 6;140(1–2):167–70.

- Huggins LG, Colella V, Atapattu U, Koehler AV, Traub RJ. Nanopore Sequencing Using the Full-Length 16S rRNA Gene for Detection of Blood-Borne Bacteria in Dogs Reveals a Novel Species of Hemotropic Mycoplasma. Microbiol Spectr. 2022 Oct 17;e0308822.

- Lashnits E, Grant S, Thomas B, Qurollo B, Breitschwerdt EB. Evidence for vertical transmission of Mycoplasma haemocanis, but not Ehrlichia ewingii, in a dog. J Vet Intern Med. 2019 Jul;33(4):1747–52.

- Pryor WH, Bradbury RP. Haemobartonella canis infection in research dogs. Lab Anim Sci. 1975 Oct;25(5):566–9.

- Carr DT, Essex HE. Bartonellosis: A Cause of Severe Anemia in Splenectomized Dogs. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1944 Oct 1;57(1):44–5.

- Donovan EF, Loeb WF. Hemobartonellosis in the dog. Vet Med. 1960;55:57–62.

- Benjamin MM, Lumb WV. Haemobartonella canis infection in a dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1959 Oct 1;135:388–90.

- Seneviratna P, Weerasinghe null, Ariyadasa S. Transmission of Haemobartonella canis by the dog tick, Rhipicephalus sanguineus. Res Vet Sci. 1973 Jan;14(1):112–4.

- Kemming G, Messick JB, Mueller W, Enders G, Meisner F, Muenzing S, et al. Can we continue research in splenectomized dogs? Mycoplasma haemocanis: old problem–new insight. Eur Surg Res. 2004 Aug;36(4):198–205.

- Austerman JW. Haemobartonellosis in a nonsplenectomized dog. Vet Med Small Anim Clin. 1979 Jul;74(7):954.

- Gretillat S. Haemobartonella canis (Kiküth, 1928) in the blood of dogs with parvovirus disease. J Small Anim Pract. 1981 Oct;22(10):647–53.

- Hulme-Moir KL, Barker EN, Stonelake A, Helps CR, Tasker S. Use of real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction to monitor antibiotic therapy in a dog with naturally acquired Mycoplasma haemocanis infection. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2010 Jul;22(4):582–7.

- Bundza A, Lumsden JH, McSherry BJ, Valli VE, Jazen EA. Haemobartonellosis in a dog in association with Coombs’ positive anemia. Can Vet J. 1976 Oct;17(10):267–70.

- Warman SM, Helps CR, Barker EN, Day S, Sturgess K, Day MJ, et al. Haemoplasma infection is not a common cause of canine immune-mediated haemolytic anaemia in the UK. J Small Anim Pract. 2010 Oct;51(10):534–9.

- Garden OA, Kidd L, Mexas AM, Chang YM, Jeffery U, Blois SL, et al. ACVIM consensus statement on the diagnosis of immune-mediated hemolytic anemia in dogs and cats. J Vet Intern Med. 2019 Mar;33(2):313–34.