Interpretation:

Mixed inflammation, chiefly eosinophilic, suppurative and histiocytic with hepatocellular atypia attributed to reactive change with cholestasis

Explanation

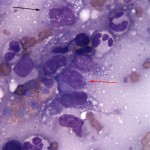

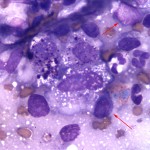

The sample is highly cellular and comprised of many aggregates of hepatocytes, exhibiting mild to moderate anisocytosis and anisokaryosis with mild cytoplasmic vacuolization and lipofuscin (a common age-related change). Also noted are bile plugs within bile canaliculi (Question 2), indicating cholestasis (which accounts for the hyperbilirubinemia and bilirubinuria). These changes were attributed to the overwhelming inflammatory response noted in the sample, comprised of large numbers of eosinophils, nondegenerate neutrophils, macrophages, monocytes, reactive fibroblasts and lymphocytes (Question 1, see Figure 3a below). Of interest is that large numbers of macrophages contain fine to globular magenta cytoplasmic granules of uncertain origin and it was initially hypothesized that this granulation indicated phagocytosis and degradation of possible mast cells granules (see Figure 4 below). Only rare definitively identified, well-differentiated mast cells were seen.

A definitive cause for the underlying inflammation was not initially determined, but due to the marked inflammatory response and the specific inflammatory components present, an underlying neoplasm driving the inflammatory response (e.g. lymphoma or mast cell tumor) was strongly suspected. Lymphoma was a top differential diagnosis due to the population of lymphocytes present (Question 3). Low numbers of small, normal appearing lymphocytes with mature chromatin pattern were present, along with more abundant numbers of intermediately sized lymphocytes with round to slightly clefted nuclei, smooth to slightly clumped chromatin, a single prominent nucleolus and mild to moderately expanded deeply basophilic cytoplasm (see Figures 3a and 4 below). Given the overall robust mixed inflammatory response and very heterogeneous sample, these atypical appearing lymphocytes were not definitively diagnostic for lymphoma on their own, but were suspicious for the disease. Alternatively, the marked accumulation of magenta granules within some macrophages was suspicious for a possible underlying mast cell tumor.

|

|

Case follow up

Due to underlying suspected neoplasia without an obvious alternative cause and rapid clinical decline, humane euthanasia was elected for the cat. Neither a necropsy nor histopathology of the liver mass lesion was performed. However, PCR for antigen receptor gene rearrangement (PARR) was performed on a cytology smear preparation and indicated a clonal expansion of lymphocytes, which was further suggestive of underlying lymphoma (T cell origin).

Discussion

Lymphoma is a common neoplasm in cats, however there has been a shift in the signalment and presentation of the disease since the wide-spread institution of vaccination for feline leukemia virus (FeLV). Prior to the 1980’s feline lymphoma was often associated with FeLV and presented with mediastinal and multicentric distributions in young cats.1 With a decreased incidence of FeLV, lymphoma is more likely to present with intra-abdominal involvement (chiefly the GI tract, intra-abdominal lymph nodes and kidneys) in older felines. Lymphoma can present in the liver in cats, but often in combination with other intra-abdominal organ involvement.1,2 It is rare to have solitary hepatic lymphoma in cats.1,2 Although no additional lesions were identified via imagining in our case subject, a necropsy was not performed to fully rule out additional organ involvement in this case.

The cytological picture was further confounded in this case due to a robust, heterogeneous population of inflammatory cells, which overlapped with the neoplastic cells. Inflammation can often occur within a tumor due to intralesional necrosis (not appreciated cytologically in this case) and/or a paraneoplastic response. Paraneoplastic syndromes, especially hypereosinophilic syndrome, are well-documented in humans with lymphoma (most often T-cell variants). This latter phenomenon is attributed to production of IL-3, IL-5 and GM-CSF by neoplastic T lymphocytes with the cumulative result being increased survival, production and recruitment of eosinophils.3 This process may result in peripheral blood hypereosinophilia, infiltration of eosinophils into the tumor itself or both.3 In veterinary medicine, paraneoplastic hypereosinophilic syndrome has been reported in dogs, cats and horses. Gastrointestinal T-cell lymphoma has most frequently been associated with hypereosinophilic syndrome in cats, but has also occurred in conjunction with transitional cell carcinoma in this species.4-6 In dogs, hypereosinophilic syndrome has been documented in association with lymphoma, mammary carcinoma, fibrosarcoma and a rectal adenomatous polyp, while lymphoma is the primary underlying neoplasm associated with the disorder in horses.7-11

Although histopathological examination was not possible in this case, we were able to utilize PARR to investigate an underlying cause for the robust inflammation further. Interpreted within the overall context of a case, PARR can be useful for parsing out a clonal population of neoplastic cells lurking within a reactive inflammatory milieu.12 Under normal circumstances, B and T lymphocytes utilize rearrangement of the VDJ region of their T and B-cell receptors to achieve polyclonal expansion of an array of different types of lymphocytes. On the other hand, neoplastic lymphocytes are essentially clones of one another and therefore an expansion of neoplastic cells will demonstrate identical, clonal rearrangement of the VDJ region, which can be identified using PCR technology. In our case, PARR identified an underlying clonal expansion of T lymphocytes indicative of T cell lymphoma, which correlated to the cytological picture (especially the eosinophilic inflammatory component). It is always imperative, however, that PARR be interpreted within the overall context of the case as false positive (and false negative) results may occur.12 It is still recommended to confirm PARR results with other diagnostic tests (e.g. histopathology, flow cytometry and immunophenotyping) and the test is not recommended for phenotyping (B versus T). The sensitivity of PARR in cats is generally fairly low (approximately 65%), but the specificity is considered fairly high, meaning a positive result is diagnostically supportive for lymphoma versus a reactive process.12

References

- Withrow SJ and Vail DM. Small Animal Clinical Oncology. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elseveier, 2007. 733-769.

- Moore A. 2013. Extranodal lymphoma in the cat – prognostic factors and treatment options. J Fel Med Surg 15, 379-390.

- Roufosse F, Garaud S and de Leval L. 2012. Lymphoproliferative disorders associated with hypereosinophilia. Semin Hematol 49, 138-148.

- LaPointe JM, Higgins RJ, Kortz GD, et al. 1997. Intravascular malignant T-cell lymphoma (malignant angioendoteliomatosis) in a cat. Vet Path 34, 247-250.

- Barrs VR, Beatty JA, McCandlish IA, Kipar A. 2002. Hypereosinophilic paraneoplastic syndrome in a cat with intestinal T cell lymphosarcoma. J Small Anim Pract 43, 401-405.

- Sellon RK, Rottman JB, Jordan HL, et al. 1992. Hypereosinophilia associated with transitional cell carcinoma in a cat. J Am Vet Med Assoc 201, 737-738.

- Marchetti V, Benetti C, Citi S and Taccini V. 2005. Paraneoplastic hypereosinophilia in a dog with intestinal T-cell lymphoma. Vet Clin Path 34, 259-263.

- Losco PE. 1992. Local and peripheral eosinophilia in a dog with anaplastic mammary carcinoma. Vet Path 23, 535-538.

- Thompson JP, Christopher MM, Ellison GW, et al. 1992. Paraneoplastic leukocytosis associated with rectal adenomatous polyp in a dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc 201, 737-738.

- Duckett WM and Matthews HK. 1997. Hypereosinophilia in a horse with intestinal lymphosarcoma. Can Vet J 38, 719-720.

- La Perle KM, Piercy RJ, Long JF, et. al. 1998. Multisystemic, eosinophilic, epitheliotropic disease with intestinal lymphosarcoma in a horse. Vet Pathol 35, 144-146.

- Burkhard MJ and Bienzle D. 2013. Making Sense of Lymphoma Diagnostics in Small Animal Patients. Vet Clin Small Anim 43, 1331-1347.

Authored by: Dr. L. Brandt.