Interpretation

Calcinosis circumscripta with predominantly histiocytic (granulomatous) inflammation

Explanation

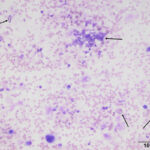

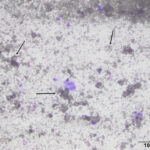

The submitted smears from both sites mostly had similar findings. The smears were moderately to highly cellular and composed of inflammatory cells with a moderate to large amount of mineralized material in the background. The smears from the right greater trochanter mass also contained a moderate amount of blood. The inflammatory cells consisted mostly of macrophages with several multinucleated forms and low numbers of non-degenerate neutrophils. Small lymphocytes were rare and only seen in the smears of the aspirate of the right greater trochanter mass. The mineralized material was present in large chunks and dispersed throughout the smears. The material ranged from finely granular to coarse elongated to amorphous structures that was colorless to pale yellow-brown and occasionally refractile (Figures 1-3). The mineralized material is consistent with calcium deposition (Question 1). Based on the patient’s signalment, description of the lesions, and cytologic findings, the masses were interpreted as calcinosis circumscripta (Question 2). Another entity that can show calcium deposits in the skin is calcinosis cutis (Question 2), however the gross appearance of this condition is different, and calcinosis cutis usually occurs in dogs with hyperadrenocorticism or treated with exogenous corticosteroids.2

|

|

|

Discussion

Calcinosis is a general term used for the abnormal accumulation of calcium salts within any soft tissue, such as the skin and muscle. Calcium deposits can occur as a result of dystrophic or metastatic calcification, iatrogenic administration of calcium-containing solutions), or unknown causes. Dystrophic mineralization develops secondary to tissue injury, necrosis or degeneration of cutaneous components (e.g., follicular cysts), whereas metastatic mineralization occurs secondary to alterations in calcium and phosphorus utilization. Two of the more recognized forms of cutaneous mineralization are calcinosis cutis and calcinosis circumscripta. Although both entities occur as a result of calcium deposition within the skin, their underlying causes and clinical manifestations differ.

Calcinosis cutis most frequently occurs due to excessive amounts of glucocorticoids within the body, which can be from an endogenous (i.e., hyperadrenocorticism) or exogenous (i.e., administration of glucocorticoids) source. A few affected dogs have renal disease, without obvious exposure to excess corticosteroids.2 These lesions are multifocal and usually present as papules, plaques, or small nodules that can be inflamed or ulcerated.2-3 Calcinosis universalis is a term used when there is a larger, more widespread, area of calcinosis cutis.3 Similar to calcinosis cutis, the calcification can occur secondary to excess glucocorticoids, as well as injections of calcium-containing solutions, and percutaneous absorption of calcium-containing products (e.g., calcium chloride containing de-icers).3

In contrast to calcinosis cutis, the pathogenesis of calcinosis circumscripta (used to be called “tumoral calcinosis”) is not well understood and it may be due to multiple different causes. The most common proposed cause is dystrophic mineralization secondary to trauma at the site of the lesion, given that the masses usually are seen at or near pressure points and boney prominences. These lesions consistently have an associated granulomatous inflammatory reaction, which lends support to the dystrophic mineralization pathogenesis theory.3 Calcinosis circumscripta more frequently presents as a localized, solitary mass but can be seen as multiple masses.3 This condition is commonly seen in young, large breed dogs that are usually less than 2 years of age, although small breed dogs and older dogs can also be affected.3–5 German shepherd dogs appear to have a predisposition.3,5 In one retrospective study of 77 dogs, Labrador Retrievers and Rottweilers were the second and third most frequently affected breeds.5 Other causes and related conditions associated with the formation of these lesions include foreign bodies, specifically polydioxanone suture material, injection sites, bite wounds, and chronic inflammation. The footpads of dogs and cats with renal disease may also have calcium deposits.3,4,6 Calcinosis circumscripta has also been reported to occur in the tongue, and vertebral column, and on the pinna and cheeks of Boxer dogs and Boston terriers.3,4,7,8 Complete surgical excision is curative with no evidence of recurrence.5

Diagnosis of calcinosis circumscripta is based on the typical signalment, clinical findings, radiographic evaluation, and biopsy with histopathologic examination.9,10 Although histopathologic examination is recommended for diagnosis, fine-needle aspiration with cytologic examination can be definitive, when interpreted in conjunction with the above clinical and diagnostic findings.9-11 Cytochemical stains to identify calcium (i.e., von Kossa and Alizarin red S) in cytologic smears can also aid in the definitive cytologic diagnosis of calcinosis circumscripta.11

Although this patient was later discovered to be on immunosuppressive therapy, which included glucocorticoids, for an immune-mediated disease, the diagnosis of calcinosis circumscripta was based on the patient’s signalment, and description and location of the mass, along with the cytologic findings. However, it is possible that the immunosuppressive doses of methylprednisone contributed to the development of the calcinosis in this case.

Author: S Chu.

References

- Bizikova P, Linder KE, Wofford JA, Mamo LB, Dunston SM, Olivry T. Canine epidermolysis bullosa acquisita: a retrospective study of 20 cases. Vet Dermatol. 2015;26(6):441-e103.

- Doerr KA, Outerbridge CA, White SD, Kass PH, Shiraki R, Lam AT, Affolter VA. Calcinosis cutis in dogs: histopathological and clinical analysis of 46 cases. Vet Dermatol. 2013;24(3):355–361.

- Ginn GE, Mansell JEK, Rakich PM. Skin and appendages. In: Jubb KVF, Kennedy PC, Palmer N, eds. Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 1. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2007:553-781.

- Gross TL. Calcinosis circumscripta and renal dysplasia in a dog. Vet Dermatol. 1997;8(1):27-32.

- Tafti AK, Hanna P, Bourque AC. Calcinosis Circumscripta in the Dog: A Retrospective Pathological Study. J Vet Med Ser A. 2005;52(1):13-17.

- Kirby BM, Knoll JS, Manley PA, Miller LM. Calcinosis Circumscripta Associated with Polydioxanone Suture in Two Young Dogs. Vet Surg. 1989;18(3):216-220.

- Zotti A, Banzato T, Mandara MT, Bernava A, Bernardini M. What Is Your Diagnosis? J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2014;244(3):283-285.

- Collados J, Rodríguez-Bertos A, Peña L, Rodríguez-Quirós J, Roman FS. Lingual Calcinosis Circumscripta in a Dog. J Vet Dent. 2002;19(1):19-21.

- Sharkey L, Gliatto J, Gallagher J. Deep Tissue Mass Aspirate from a Young German Shepherd Dog. Vet Clin Pathol. 1999;28(4):147-149.

- Bettini G, Morini M, Campagna F, Preziosi R. True grit: the tale of a subcutaneous mass in a dog. Vet Clin Pathol. 2005;34(1):73-75.

- Marcos R, Santos M, Oliveira J, Vieira MJ, Vieira AL, Rocha E. Cytochemical detection of calcium in a case of calcinosis circumscripta in a dog. Vet Clin Pathol. 2006;35(2):239-242.