Interpretation

Suppurative inflammation with intralesional spirochete bacteria consistent with Borrelia burgdorferi.

Explanation

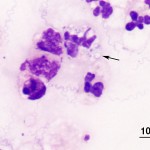

Both right and left vitreous samples were of increased cellularity and consisted predominantly of neutrophils with fewer macrophages, confirming the presence of suppurative uveitis (Question 1). Equine uveitis is a common cause of blindness in horses and cases are often classified as single episodes of primary uveitis or recurrent uveitis, if the symptoms return or persist.1 Equine recurrent uveitis (ERU) is the term often applied in these latter cases and would apply in this patient given the clinical history. Infectious agents are not commonly recovered from horses with uveitis (either primary or recurrent) making this case unusual since both vitreous samples contained numerous slender, spirochete-like bacterial organisms (Question 2). The organisms were light blue, approximately 0.2 um wide, 10-15 um long with fine tapered ends and 3-8 loose spirals; note that some are phagocytized within neutrophils (arrow Figure 3). Differential diagnoses for this type of organism include Borrelia, Leptospira and Treponema spp. (Question 3). Both Leptospira and Borrelia spp. have been associated with equine uveitis, although the morphologic features and staining properties in this case were most consistent with Borrelia spp. (Leptospira spp. typically have tighter spirals and stain poorly with Wright’s stain2). Samples of aqueous humor were also submitted and displayed inflammation, although the inflammation was more mixed and no infectious agents were identified.

|

Further diagnostic testing included serologic testing for both Leptospira spp. and Borrelia spp. along with polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing of ocular fluids for DNA of both organisms (Question 4). Interestingly, when the uveitis was first noted several months prior, serologic testing of the patient was performed on serum for the common Leptospira interogans serovars and revealed all titers below 100. In addition, a Lyme kinetic ELISA test for antibodies to Borrelia burgdorferri was equivocal and a subsequent Western blot test for antibodies against Borrelia antigens was negative. These tests were repeated on presentation and were negative for exposure to these agents. However PCR testing of the ocular fluids revealed that samples from both the right and left vitreous humor were PCR positive for B. burgdorferi DNA and negative for Leptospiral DNA. Antibodies were also measured in the vitreous samples using the Lyme multiplex assay at Cornell University and revealed positive antibody values for OspA and OspF, the latter being a marker of chronic infection.3 On histopathologic of ocular tissue obtained from necropsy, similar findings were seen in both eyes. These findings included multiple perivascular accumulations of neutrophils, macrophages, lymphocytes and fewer plasma cells in the iris, filtration angle and choroid. Neutrophils and macrophages were also scattered in the aqueous and vitreous humors and retinal detachment was noted in both eyes. No bacteria were seen on hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections but low numbers of spirochete bacteria were identified within the cellular exudate in the vitreous humor on a Modified Steiner silver-stained section.

Discussion

Borrelia burgdorferi is the etiologic agent of Lyme disease and was first described in humans in Lyme, Connecticut, in 1975. Although first identified in horses in 1985, recent serologic testing of horses in the Northeastern United States revealed seropositivity rates of 40% or more. This spirochete organism is transmitted by the tick vectors of the Ixodes genus and can be transmitted along with other infectious agents, such as Anaplasma phagocytophillum, resulting in co-infections.4

Clinical signs attributed to Lyme disease in horses are often non-specific and variable but are uncommon, even in experimental infections.5 Equine borreliosis has been implicated in musculoskeletal, neurological and dermatologic disorders as well as uveitis and non-specific symptoms such as fever and lethargy.4,6 Although there have been previous reports of equine uveitis associated with B. burgdorferi,7,8 these reported cases and the current case are unusual since infectious agents are rarely recovered from horses with uveitis with Leptospira spp. being the more commonly identified pathogen.9 In humans, three stages of Lyme disease are recognized, starting with a localized rash at the tick bite site, which may be accompanied by flu-like symptoms. The second stage, when infection disseminates, can result in a variety of symptoms depending on the organ systems affected. Some patients will then develop polyarthritis and neurologic dysfunction if left untreated.10 Ocular manifestations of Lyme disease in people are uncommon but have been reported.11

Diagnosis of Lyme disease is challenging in both animals and humans and involves a combination of history of tick exposure in endemic areas, clinical signs consistent with the disease, PCR testing for Borrelia DNA, serologic testing for exposure to the organism and possibly response to treatment.12 In the past, serologic testing was done as a two-tiered approach as was first done in this case: an initial ELISA test followed by a confirmatory Western blot.4 Newer, more sensitive tests, including the Lyme multiplex assay3 are now in use. Regardless of the methodology used, serologic positivity does not differentiate between exposure and an active infection in any species, so other findings need to be considered including patient clinical signs, history of tick exposure and identification of the organism or its DNA in tissue or fluid.

It is interesting that on the basis of serologic testing on blood, this patient was considered seronegative. Lack of seroconversion has also been reported in people from which B. burgdorferi was isolated.13 This could be due to early development of clinical signs prior to production of enough antibodies for detection or the ability of the organism to evade the host immune response by residing in immunologically privileged sites, including the central nervous system or eye.4 The latter scenario would fit with the current case, as antibodies were detectable in ocular fluid but not in the serum and clinical signs had been present for several months.

This case illustrates some of the challenges in the recognition and diagnosis of equine Lyme disease. Although Lyme borreliosis is only one of many possible causes of equine uveitis, it should be considered as a differential diagnosis, especially in endemic areas. Given the negative serum tests in this case and the failure of these tests to confirm infection, cytologic assessment, antibody and/or PCR testing of ocular fluids may be worthwhile in cases where clinical suspicion is high. Unfortunately, equine vitreous sampling can be difficult and not without risks, which need to be considered on a case by case basis.

Note: This case has been published as part of a case report of Borrelia-associated uveitis in two horses.14

References

- Hollingsworth SR. Diseases of the uvea. In: Equine ophthalmology. 2nd ed. Gilger BC, ed. 2nd ed. St. Louis, Mo. Elsevier Saunders; 2011. p. 274.

- Carter GR(R). Spirochetes. In: Essentials of veterinary microbiology. 5th ed. Carter GR, Chengappa MM, Roberts AW, eds. Baltimore, Md: Williams & Wilkins; 1995; pp 221-223.

- Wagner B, Freer H, Rollins A, Erb HN, Lu Z, Grohn Y. Development of a multiplex assay for the detection of antibodies to Borrelia burgdorferi in horses and its validation using Bayesian and conventional statistical methods. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 2011; 144:374-81.

- Butler CM, Houwers DJ, Jongejan F, van der Kolk JH. Borrelia burgdorferi infections with special reference to horses. A review. Vet Q 2005; 27:146-156.

- Chang YF, Novosol V, McDonough SP, Chang CF, Jacobson RH, Divers T, et al. Experimental infection of ponies with Borrelia burgdorferi by exposure to Ixodid ticks. Vet Pathol 2000; 37:68-76.

- Sears KP, Divers TJ, Neff RT, Miller WH Jr, McDonough SP. A case of Borrelia-associated pseudolymphoma in a horse. Vet Dermatol 2012; 23:153-6.

- Burgess EC, Gillette D, Pickett JP. Arthritis and panuveitis as manifestations of Borrelia burgdorferi infection in a Wisconsin pony. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1986; 189:1340-1342.

- Hahn CN, Mayhew IG, Whitwell KE, Smith KC, Carey D, Carter SD, et al. A possible case of Lyme borreliosis in a horse in the UK. Equine Vet J 1996; 28:84-88.

- Wollanke B, Rohrbach BW, Gerhards H. Serum and vitreous humor antibody titers in and isolation of Leptospira interrogans from horses with recurrent uveitis. J Am Vet Med Assoc2001; 219:795-800.

- Steere AC, Bartenhagen NH, Craft JE, Hutchinson GJ, Newman JH, Pachner AR, et al. Clinical manifestations of Lyme disease. Zentralbl Bakteriol Mikrobiol Hyg A 1986; 263:201-205.

- Mikkila HO, Seppala IJ, Viljanen MK, Peltomaa MP, Karma A. The expanding clinical spectrum of ocular lyme borreliosis. Ophthalmology 2000; 107:581-587.

- Krupka I, Straubinger RK. Lyme borreliosis in dogs and cats: background, diagnosis, treatment and prevention of infections with Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2010; 40:1103-1119.

- Mikkila H, Karma A, Viljanen M, Seppala I. The laboratory diagnosis of ocular Lyme borreliosis. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 1999; 237:225-230.

- Priest HL, Irby NL, Schlafer DH, Divers TJ, Wagner B, Glaser AL, et al. Diagnosis of Borrelia-associated uveitis in two horses. Vet Ophthalmol 2012; 15:398-405.