Interpretation

Moderate neutrophilic pleocytosis due to Cryptococcus spp. infection

Explanation

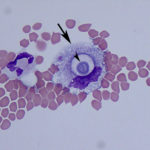

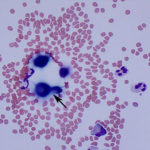

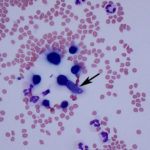

While performing the manual cell counts on the hemocytometer, multiple round, variably sized (4-20μm) organisms surrounded by a large capsule were observed. The objects out of the plane of focus in Figure 1 are RBCs, for size comparison. The organism’s size, capsule, and narrow-based budding, which was clearly evident on the hemocytometer (Figure 1B) were consistent with Cryptococcus spp. yeast (Question 2). Evaluation of the Wright’s stained cytocentrifuged smears confirmed this interpretation, however the capsule was less apparent in this preparation. The inflammation was neutrophilic, characterized by 95% non-degenerate neutrophils (Question 1). The remaining 5% of nucleated cells consisted of macrophages and lymphoid cells, including small and intermediate-sized lymphocytes and rare plasma cells, indicating antigenic stimulation. Macrophages were noted to contain phagocytized crypotococcal organisms (Figure 3B). Interestingly, a rare organism demonstrating pseudohyphae formation was observed (Figure 5). No erythrophagia or other evidence of in vivo hemorrhage (e.g. hematoidin crystals, hemosiderin) was seen, therefore the RBCs in the sample were likely due to tap-related contamination (Question 3). This is supported by the presence of platelets (Figure 2B). Note that, peracute hemorrhage would appear cytologically similar, therefore the distinction is best made clinically by observing the color of the fluid during sample collection. A red-tinged fluid throughout fluid aspiration would support true hemorrhage, whereas a brief spurt of blood, often when moving the needle, suggests iatrogenic blood contamination from a vessel.

Additional diagnostics

A Cryptococcus serum antigen assay was positive (1:64), however polymerase chain reaction testing to speciate the organism was negative for C. neoformans var. neoformans. The most likely explanation for the negative result is an infection with a different Cryptococcus species, such as C. gatti or C. albidus.

Discussion

Cryptococcosis is the most common systemic fungal disease in cats worldwide, mainly caused by Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii.1 Other species reportedly infectious to domestic animals include C. albidus, C. magnus, and C. laurentii.2 In the United States, infections are most frequently reported in the west.1,3 C. gatti has more recently emerged as a primary pathogen in North America, particularly in the Pacific Northwest.2 C. neoformans is found in the environment in avian (mainly pigeon) feces, and both C. neoformans and C. gatti can be found within certain decaying plant matter, such as eucalyptus.1,4 Somewhat counterintuitively, lifestyle does not appear to be a risk factor, with nearly a quarter of infected cats being indoor only in one case series.3 In humans, C. neoformans is considered an opportunistic pathogen infecting the immunocompromised, while in dogs and cats, it is generally considered a primary pathogen.2 Infection with FeLV or FIV is also not considered a risk factor for cats, however it may hinder clearance of the fungal infection.2,3

Cryptococcus is a dimorphic fungus, existing as a filamentous basidiospore in the environment, and converting to a yeast form (blastoconidia) in host tissue, where it reproduces asexually by budding.1,2 Infection is thought to occur through inhalation of small (2-3µm) basidiospores, however desiccated yeast in the environment may also be infectious.1,2 Following inhalation, the nasal cavity is colonized, however clinical disease does not always develop.1,2 Nasal tissue is the most commonly confirmed infected site in cats and can manifest as a polyp-like mass or nasal deformity, and result in chronic unilateral or bilateral upper respiratory signs.1,3 After an incubation period that is considered highly variable (months to years), the infection may invade local tissue (e.g. cribriform plate to meninges, optic nerve to eye) or disseminate hematogenously, presumably via macrophages, to distant sites, including skin, lungs, lymph nodes, urinary tract, or other less common sites (e.g. mediastinum, gingiva, spleen, heart, liver, thyroid).1–3

While cats are reportedly eight times more likely to be diagnosed with cryptococcosis than dogs, dogs appear to have a higher incidence of central nervous system (CNS) involvement.3 Reported clinical signs in feline cases of CNS cryptococcosis include lethargy, behavioral changes, abnormal gait, vestibular signs, seizures, mydriasis, blindness, and facial twitching.5 Extraneural signs (e.g. lethargy, inappetence, respiratory and cutaneous lesions) preceded neurologic signs in 72% of cats in one study with a duration ranging from a week to as long as 4 years.5 Ocular abnormalities are suggestive of concurrent CNS involvement, and can include chorioretinitis, as seen in this case, exudative retinal detachment, optic neuritis, papilleodema, and retinal hemorrhage.1 Cats may present with sudden blindness.1

The diagnostic workup of neurologic signs includes imaging and CSF analysis. In the case reported here, diffuse meningeal enhancement was observed on magnetic resonance imaging, and helped decrease suspicion of a primary brain neoplasm, and increase the likelihood of an infectious/inflammatory process. However, single or multifocal granulomatous mass lesions, also known as “cryptococcomas” can occur.1,5 While cytologic evaluation of CSF often confirms a clinical suspicion of CNS disease, it is rarely specific for an underlying cause. However, a diagnosis of Cryptococcus infection can often be made through visualization of the cryptococcal organisms in CSF, as in the case reported here. In one case series, 90% of cats (9/10), in which a CSF analysis was done, had a pleocytosis (range 0-1440, mean 201, median 21 cells/µL).5 As in this case, the pleocytosis is typically neutrophilic in cats, while dogs tend to have a predominance of large mononuclear cells.5 The CSF total protein in cats can also be normal or increased (range 8-132, median 39, mean 45 mg/dL).5 Organisms have been reportedly seen in CSF cytocentrifuge preparations from 82% (9/11) of infected cats.3,5 Therefore, the absence of organisms in CSF cytological specimens does not rule out a cryptococcal infection. In clinical samples, Cryptococcus is typically identified as 4-20µm diameter spherical to oval yeast, which are surrounded by a mucopolysaccharide capsule and display narrow-based budding.6 Cryptococcus’ characteristic narrow-based budding and large capsule distinguish it morphologically from Blastomyces, which displays broad-based budding and lacks a capsule.2 However, C. neoformans and C. gattii have also rarely been reported to demonstrate atypical morphologic appearances including yeast organisms without a capsule (or arguably a very small or non-visible capsule), chains of budding yeast, pseudohyphae, hyphae, and germ tube structures.6–8 The hyphal and pseudohyphal forms of Cryptococcus are considered less virulent.8 Therefore variations in the classic morphologic appearance, as in this case, should not rule out infection with Cryptococcus spp.

The latex agglutination assay for the cryptococcal polysaccharide capsular antigen can be run on CSF, serum, plasma, or urine, as a means to diagnosis cryptococcosis.1 On serum, the test is highly sensitive (90-100%) and specific (97-100%).1 However, false negatives can occur with localized infections (e.g. nasal, ocular).3 Submission of CSF for antigen titers and fungal culture is recommended in cases of suspected CNS cryptococcosis, when serum titers are negative and no organisms are seen cytologically.1 A titer of 1:2 is considered positive, however a result of ≤1:200 may be a false positive and other confirmatory tests (e.g. cytology, culture) should be performed to make a definitive diagnosis.1,2 Note that cytologic evaluation cannot distinguish between the species of Cryptococcus.2 Fungal culture can differentiate between C. neoformans and C. gattii.1,2,4 The yeast form of Cryptococcus can be readily cultured, is not a hazard to laboratory personnel, and can be used for determination of antifungal susceptibility.1,2 Molecular classification can also be performed at several reference laboratories, but is not routinely used in practice.2,4

Treatment guidelines have not been established due to the multitude of factors that impact drug choice, including the presence of potential co-morbidities.4 Fluconazole is typically the first-line treatment in cats with localized disease, due to its low cost, minimal side effects, and good penetration into the eye, urinary tract, and brain.1,4 However, amphotericin B may be superior for CNS infections.2,4 The administration of short-term glucocorticoids in conjunction with antifungals minimizes the acute inflammatory response to the dying yeast, and is associated with improved survival in the first 10 days.1,4,5 Treatment is prolonged, for months to even years, and is recommended to be continued until the antigen test is negative.1,2 Serial antigen titers allow for monitoring of therapy and consistency of interpretation should be performed by the same laboratory.1 Clinical improvement is often appreciated prior to a reduction in titer.1 Repeat serum antigen titers should also be performed at least 1 month after discontinuation of treatment and periodic antigen testing may also be worthwhile, as relapse can occur weeks to years later.1,2 Importantly for owners of infected cats, Cryptococcus is not considered a zoonosis.4

Prognosis is variable, and interestingly there is no apparent correlation between pre-treatment antigen titer and outcome.1 Involvement of the CNS carries a worse prognosis compared to other forms of cryptococcosis in cats.1 Altered mentation is a negative prognostic indicator in cases of CNS cryptococcosis.5 While a median survival time (MST) of only 13 days (0-4,050 days) was reported in a case series of cats with CNS cryptococcosis, the MST was not reached for those cats that survived at least 3 days after diagnosis.5 Therefore, there is benefit to attempting treatment, as long term survival is achievable.

Case Follow-up

The cat was started on fluconazole and a tapering course of prednisolone. At the 6-week recheck exam, the owner reported that the head tilt and sneezing had resolved, no more collapse episodes had occurred, and dramatic improvement was noted on physical examination. Blood was drawn and submitted for repeat titers, which were unchanged (1:64). At the 12-week recheck, a recheck titer was negative. Clinically, the owner had not observed any new collapse episodes and only noticed an occasional head tilt. Based on the resolution of clinical signs and the negative antigen titer, it was recommended that the patient discontinue fluconazole treatment in four weeks and return for another recheck appointment in eight weeks. Based on the recommendation of his primary care veterinarian, the cat has reportedly continued to receive prednisolone as treatment for previously diagnosed allergies.

In retrospect, it was thought that the collapse events for which the patient initially presented were unlikely to have been syncopal episodes, but rather vestibular events. Additionally, the markedly increased CK activity identified on intake was hypothesized to be due to a fall from a high location, after a vestibular event, not witnessed by the owner.

References

- Trivedi SR, Malik R, Meyer W, Sykes JE. Feline cryptococcosis. Impact of current research on clinical management. J Feline Med Surg. 2011;13(3):163–72.

- Lester SJ, Malik R, Bartlett KH, Duncan CG. Cryptococcosis: Update and emergence of Cryptococcus gattii. Vet Clin Pathol. 2011;40(1):4–17.

- Trivedi SR, Sykes JE, Cannon MS, Wisner ER, Meyer W, Sturges BK, et al. Clinical features and epidemiology of cryptococcosis in cats and dogs in California: 93 cases (1988-2010). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2011;239(3):357–69.

- Pennisi MG, Hartmann K, Lloret A, Ferrer L, Addie D, Belák S, et al. Cryptococcosis in cats: ABCD guidelines on prevention and management. J Feline Med Surg. 2013;15(7):611–8.

- Sykes JE, Sturges BK, Cannon MS, Gericota B, Higgins RJ, Trivedi SR, et al. Clinical Signs, Imaging Features, Neuropathology, and Outcome in Cats and Dogs with Central Nervous System Cryptococcosis from California. J Vet Intern Med. 2010;24(6):1427–38.

- Gazzoni AF, Oliveira F de M, Salles EF, Mayayo E, Guarro J, Capilla J, et al. Unusual morphologies of cryptococcus spp. in tissue specimens: Report of 10 cases. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2010;52(3):145–9.

- Evans SJM, Jones K, Moore AR. Atypical Morphology and Disparate Speciation in a Case of Feline Cryptococcosis. Mycopathologia. 2017;1–6.

- Lin J, Idnurm A, Lin X. Morphology and its underlying genetic regulation impact the interaction between Cryptococcus neoformans and its hosts. Med Mycol. 2015;53(5):493–504.

Authored by: H. Brodlie (class of 2018) and A. Newman