Interpretation

Mycoplasma wenyonii infection.

Explanation

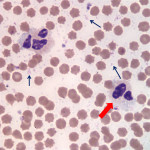

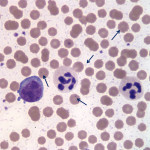

The overall quality of the blood film is fair and can still be used for interpretation, but the leukocytes are showing storage-associated changes, which makes assessment of leukocyte morphologic features more challenging (Question 1). The two leukocytes pictured in Figure 2 are obviously neutrophils and their nuclei still appear segmented, but the nuclear chromatin is lighter than it should be and the nuclei are swollen (Figure 2a). There are a few discrete margined vacuoles in the cytoplasm (which should not be misinterpreted as toxic cytoplasmic vacuolation – the latter is more indistinct vacuoles or rarefaction versus the discrete vacuoles in the neutrophils in this blood smear) and there is also polarization of neutrophil granules to one side of the cell. The erythrocytes are better preserved than the leukocytes, but almost all of the erythrocytes have spiny membrane projections, occurring at regular intervals across the surface of the cells. These red blood cells (RBC) can be referred to as echinocytes or “burr” cells (Question 2). Echinocyte formation occurs when the erythrocyte’s outer membrane leaflet expands in excess of the inner leaflet. This can occur secondary to ATP depletion (occurs with storage), administration of certain drugs, electrolyte abnormalities or cellular dehydration. In our case, the practioner also submitted a good quality, fresh blood film (Figure 3) made at the time of sample collection. Evaluation of the fresh blood film reveals normal white and red blood cell morphologic features (confirming that the echinocyte formation is due to sample aging and artifactual change in this case).

The most exciting finding, however, is the large number of microorganisms scattered throughout the background of the sample (Figure 2a) and adherent to erythrocytes in the image from the freshly made blood film (Figure 3). These organisms are compatible with Mycoplasma wenyonii (Question 3), which is a hemotrophic mycoplasma that binds to the surface of RBCs via delicate fibrils.1 The organisms typically appear as individual ring-shapes or solid round structures <1 um in diameter or in linear, chain-like formations on the surface of erythrocytes. In this case, large numbers of organisms are present on both the freshly made and aged blood films; however the morphologic features of the individual organisms are much more discernible on the fresh blood smear. Only very low numbers of organisms remain associated with RBCs in the aged blood film and the organisms are condensed into groups of slightly irregular, light purple-pink, granular structures that could easily be mistaken for stain precipitate or other debris. All hemoplasma organisms fall off of RBCs with storage in EDTA, but Mycoplasma wenyonii is especially prone to this. In general, M. wenyonii is not thought to be a cause of major clinical disease in cattle, but can lead to clinical signs in immunocompromised or stressed animals. Given the described range of clinical signs and the parasitic burden, it seems likely that the cow in our case was suffering, at least in part, from an active clinical infection of M. wenyonii (Question 3).

This case demonstrates some key features of whole blood sample aging and emphasizes the importance of concurrently submitting fresh blood smears with EDTA samples, especially in cases where evaluation for microorganisms is imperative.

|

|

Discussion

Mycoplasma wenyonii is a gram-negative, obligate RBC parasite designated as a hemotrophic mycoplasma. This organism was formerly known as Eperythrozoon wenyonii, but analysis of organism 16S ribosomal RNA caused it to be reclassified as Mycoplasma in the late 1990s.2 This organisms should not be confused with Mycoplasma bovis, which is not hemotrophic and is implicated in mastitis, pneumonia and polyarthritis in cattle.

Typically, M. wenyonii does not cause significant clinical disease in cattle, unless the animal is immunocompromised or stressed.1,3 Clinical disease has been induced in experimentally splenectomized calves and immunocompromised animals.1,2,4 Clinical signs are typically mild and include depression, fever and moderate anemia.3 Acute infections are typically transient.1,4 Chronically infected animals, however, may demonstrate scrotal, teat and hind limb swelling, lymphadenopathy, rough hair coat, decreased milk production and weight loss.5,6 This cow showed the latter clinical signs, but was not anemic, which is typical of most spontaneous cases of M. weonyonii infection. The mode of transmission is not definitively known, but arthropod vectors, direct contact and iatrogenic inoculation have all been implicated.1,4

In general, the direct pathological effects of Mycoplasma organisms may be due several mechanisms, including production of free radicals leading to oxidative cell membrane damage and release of enzymes that result in tissue damage.7 This group of organisms can also consume host nutrients and may contribute to development of autoantibodies and immune disorders.7

Treatment involves management of concurrent illnesses and tetracycline antibiotics to specifically target M. wenyonii. Affected animals are thought to be lifelong carriers, despite prolonged antibiotic treatment.7

References

1. Allison RW and Meinkoth JH. Anemia caused by Rickettsia, Mycoplasma and Protozoa. In: Weiss DJ and Wardrop KJ, editors. Schalm’s Veterinary Hematology. 6th edition. Ames: Blackwell; 2010. p. 199-210.

2. Neimark H and Kocan KM. The cell wall-less rickettsia Eperythrozoon wenyonii is a Mycoplasma. FEMS Microbiology Letters 1997:287-291.

3. Carlson GP. Diseases associated with increased erythrocyte destruction (hemolytic anemia). In: Smith BP, editor. Large Animal Internal Medicine. 4th edition. St. Louis: Mosby Elsevier; 2009. p. 1154-1163.

4. Genova SG, Streeter RN, Velguth KE, et al. Severe anemia associated with Mycoplasma wenyonii infection in a mature cow. Canadian Veterinary Journal 2011:1018-1021

5. Montes AJ, Wolfe DF, Welles EG, et al. Infertility associated with Eperythrozoon wenyonii infection in a bull. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 1994:261-263

6. Smith JA, Thrall MA, Smith JL, et al. Eperythrozoon wenyonii infection in dairy cattle. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 1990:1244-1250

7. Messick JB. Hemotrophic mycoplasma (hemoplasmas): a review and new insights into pathogenic potential. Veterinary Clinical Pathology 2004:2-13

Authored by: Dr. L.Brandt