Interpretation

Marked mixed cell pleocytosis with lymphoma of granular lymphocytes and concurrent hemorrhage.

Explanation

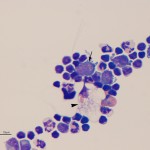

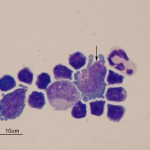

There was a marked mixed cell pleocytosis in the CSF, consisting of 62% small lymphocytes, 17% non-degenerate neutrophils and 5% macrophages (Question 1). A few eosinophils were also noted (Figure 1A), but not counted in the 100 differential leukocyte count. Approximately 16% of the nucleated cells were large lymphocytes with indented to slightly pleomorphic nuclei and small amounts of deep blue cytoplasm with a perinuclear clear zone containing <20 distinct medium to large red cytoplasmic granules (Figure 1A arrow, Figure 2A arrow). These cells are an abnormal finding in CSF and diagnostic for a particular kind of lymphoma, i.e. granular lymphocytes (Question 2). A few large more reactive appearing lymphocytes with smooth blue cytoplasm and clear cytoplasmic vacuoles were also seen (not shown). Some of the macrophages were vacuolated and demonstrated erythrophagia (Figure 1a, arrowhead). This finding indicates concurrent hemorrhage into the CSF or spinal cord (Question 3) and explains the high red blood count. Extracellular myelin whorls were also seen (not shown). The latter could be tap-associated, particularly in this lumbosacral tap,1 and is not considered of pathologic relevance when observed extracellularly. The total protein was also very high in this case and could have been due to leakage of serum proteins associated with increased vascular permeability and hemorrhage as well as intrathecal production of globulins.

|

|

Discussion

Granular lymphocytes are lymphocytes that are either cytotoxic T cells or natural killer (NK) cells. They are normally found in the red pulp of the spleen2 and mucosal surfaces, particularly in the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts, where they are involved with mucosal immunity.3 Granular lymphocytes are not a normal constituent of CSF.4 However, they can increase in CSF in reactive conditions. Granular lymphocytes have been reported in CSF of dogs with Ehrlichia canis infection and necrotizing meningoencephalitis and in horses with Equine Herpes Virus type-1 infection.5,6 However, in this case, the number of these cells in CSF, together with their large size and the large granules, were diagnostic of lymphoma versus a reactive condition.

Lymphoma of granular lymphocytes is a particular variant of lymphoma that originates in the small intestine of cats. In one series of 19 cats, 90% of cases consisted of CD3-positive T cells, with only 2 cases being negative for CD3. Most of the cases were negative for CD5, another T cell marker that consistently labels T cells in blood. The T cells expressed CD8αα (63%, including one case which lacked CD3 expression) and the mucosal integrin, CD103 or αEβ7 (58% of 17 tested cases), indicating the tumor arises from intra-epithelial lymphocytes. The cells can have a variable appearance ranging from small mature cells with fine granules to intermediate or large cells with fine or large cytoplasmic granules.7 The size of the granules or the cells does not appear to have prognostic relevance and the prognosis with this particular variant of lymphoma is uniformly poor, with mean survival of 18 to 57 days.7,8 The cytoplasmic granules are a key finding and help identify the cell lineage, however they are difficult to discern with rapid stains, such as Diff-quik®.9 They can also be readily mistaken for mast cell granules, which can result in a mistaken diagnosis of a mast cell tumor, but the granules are generally red versus purple, usually located in a focal area in the cytoplasm (typically the perinuclear clear zone) and may be surrounded by a clear space (resembling a vacuole and likely representing the membrane of the granules). These cells have also been termed large granular lymphocytes, however because the “large” adjective is unclear (large cell or large granules or both) and tumor cells and their granules can be variably sized, we prefer to use the generic term of granular lymphocytes, without a size qualifier. These cells have also been called “globule” leukocytes,10 however this is an inappropriate and non-specific term, with much debate as to the origin or even existence of a true “globule or globular” leukocyte.

Cats with this tumor typically present with non-specific signs of lethargy, anorexia, vomiting, depression and weight loss. They can have palpable abdominal masses (representing the intestinal mass or enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes) and body cavity effusions (thoracic and abdominal) may be present. Some cats have a pre-existing history of inflammatory bowel disease. Circulating tumor cells (leukemia) can be identified in peripheral blood in many cats, although they may be present in low numbers and mature lymphocytes with cytoplasmic granules are normally observed in the blood of cats. It is worthwhile to review blood smears of cats with the above presenting clinical signs, because the presence of large immature lymphocytes with red cytoplasmic granules could be a clue for the presence of (and even diagnostic for) the underlying tumor. Other reported hematologic findings are a normocytic normochromic non-regenerative anemia (likely from bone marrow suppression due to inflammatory disease) and neutrophilia, which may be secondary to mucosal ulceration (a common finding in these tumors). The tumor is not associated with Feline Leukemia Virus or Feline Immunodeficiency Virus.7,8,10 The lymphoma rapidly metastasizes to mesenteric lymph nodes, liver, spleen, bone marrow and other sites (kidney, pancreas, mediastinum, peripheral lymph nodes) and the diagnosis can be obtained by identifying neoplastic cells in body cavity effusions. Biochemical results typically reflect secondary organ involvement (particularly of the liver, with resulting icterus and increases in liver enzymes, including GGT)7,8,10 but in this case were uninformative. The high CK could be secondary to a muscle stick (contaminating blood with muscle tissue rich in CK) or in vivo muscle injury. The low ALT activity was not a relevant finding and the mildly decreased serum iron concentration could reflect a negative acute phase response or transient variation or may even have been normal for the cat. There has been one previous report of a cat with neurological signs and metastatic tumor cells in the CSF.10

Further information and follow up

Since a primary CNS lymphoma was considered unlikely, abdominal radiography or ultrasonography was recommended to identify the primary neoplasm (Question 4). However, due to the grave prognosis, the cat was euthanized. Gross examination at necropsy revealed multifocal moderate subdural hemorrhage and enlargement of the T11 dorsal root ganglion with thickening of the T11-T12 segment of the spinal cord. The intestines appeared of normal thickness and no gross lesions were detected in the latter organ. On histopathologic examination, there were diffuse infiltrates and multifocal nodules of neoplastic round cells in the ileal and ileocolic junction submucosa, confirming primary involvement of the intestine, despite the lack of an obvious mass. The cells had eccentric round nuclei, single nucleoli and small to moderate amounts of eosinophilic cytoplasm. Faint granules were seen in the cytoplasm of a few cells. The granules were negative on staining with Toluidine blue and Giemsa (which are stains for identifying mast cells granules and are typically negative for granules of these lymphocytes). Similar cells were seen in the meninges, perivascular spaces in white matter and extending along the nerve roots into the dorsal root ganglia. These lesions were found in the cord at the level of T3, T11-T12 and L4-5, indicating extensive neural involvement, particularly of the dura. No abnormalities or infiltrates of tumor cells were seen in other examined areas of small and large intestine, regional lymph nodes, liver, bone marrow or spleen. Immunostaining indicated that the cells were positive for CD3, confirming a T cell lymphoma.

Summary

This case illustrates an unusual clinical presentation of an aggressive variant of lymphoma in cats that arises from intra-epithelial T cells in the small intestinal mucosa. Recognition of the characteristic cytoplasmic granules (which may be difficult to discern in rapid cytologic stains and in histologic specimens) is key for diagnosis and prognostication of this uncommon neoplasm.

References

- Zabolotzky, S.M., et al. 2010. Prevalence and significance of extracellular myelin-like material in canine cerebrospinal fluid. Vet Clin Pathol 39, 90-95.

- Danilenko, D.M., et al. 1995. A novel canine leukointegrin, alphaD beta2, is expressed by specific macrophage subpopulations in tissue and a minor CD8+ lymphocyte subpopulation in peripheral blood. J Immunol 155, 35-44.

- Pang G., et al. 1993. Morphological, phenotypic and functional characteristics of a pure population of CD56+ CD16- CD3- large granular lymphocytes generated from human duodenal mucosa. Immunology 79, 498-505.

- Tibold A., et al. 1998. Lymphocyte subsets and CD45RA positive T-cells in normal canine cerebrospinal fluid. J Neuroimmunol 82, 90-95.

- Garmia-Aviña J. and Tyler J.W. 1999. Large granular lymphocytosis in the cerebrospinal fluid of a dog with necrotizing meningoencephalitis. J Comp Pathol 121, 83-87.

- Goodman L.B., et al. 2007. A point mutation in a herpesvirus polymerase determines neuropathogenicity. PLoS Pathog 3:e160.

- Roccabianca P. et al. 2006. Feline large granular lymphocyte (LGL) lymphoma with secondary leukemia: Primary intestinal origin with predominance of a CD3/CD8αα phenotype. Vet Pathol 43, 15-28.

- Krick E.L., et al. 2008. Description of clinical and pathological findings, treatment and outcome of feline large granular lymphocyte lymphoma (1996-2004). Vet Comp Oncol 6, 102-110.

- Allison R.W. and Velguth K.E. 2010. Appearance of granulated cells in blood stained with automated versus methanolic Romanowsky methods. Vet Clin Pathol 39, 99-104.

- Drobatz K.J., et al. 1993. Globule leukocyte tumor in six cats. JAAHA 29, 391-396.

Authored by: T Stokol