Interpretation

Neoplasia of unknown lineage

Explanation

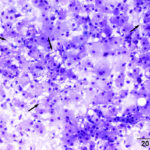

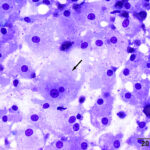

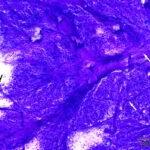

One highly cellular prestained smear was submitted, which consisted of a uniform population of round to polygonal cells present in sheets and as individualized cells in a moderately proteinaceous background. The cells had a low nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio with clear to lightly basophilic cytoplasm that contained variable numbers of pink to purple irregularly shaped granules and had indistinct outlines. Nuclei were round to oval and paracentral to central, with coarse to lightly clumped chromatin and usually single (with up to 2) prominent nucleoli. Anisocytosis and anisokaryosis were mild (Figures 1-2). Low numbers of binucleated cells with intracellular anisokaryosis were observed (Figure 1-2). Lipid-like vacuolation was observed within the cells in more spread-out regions of the smear (Figure 1). Prominent vascular profiles were seen between the cells (Figure 3). Low numbers of lymphocytes, which were mostly small cells with rare intermediate forms, and non-degenerate neutrophils were noted and interpreted as concurrent mild mixed inflammation. A diagnosis of neoplasia was made with differential diagnoses including a balloon cell melanoma, granular cell tumor, rhabdomyoma, and liposarcoma (Question 1). A poorly cohesive carcinoma, such as a clear cell adnexal carcinoma, was considered less likely, based on the mild anisokaryosis. There was concern for malignancy on initial cytologic assessment, based on the binucleation with intracellular anisokaryosis.

|

|

|

Additional tests

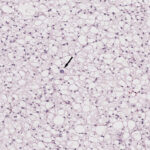

An excisional biopsy of the mass was performed and submitted for histopathologic examination. The specimen consisted of seven fragmented sections , composed of sheets of round to polygonal neoplastic cells supported by a scant amount of collagenous stroma. Most of the neoplastic cells had distinct cell borders, clear to lightly eosinophilic, highly vacuolated cytoplasm, with round to ovoid nuclei containing finely stippled chromatin and a single prominent nucleolus. A few neoplastic cells had a single large vacuole, compatible with lipid. Anisokaryosis and anisocytosis were mild, with no mitotic figures observed in ten 400x fields (2.37mm2) (Figure 4). Small numbers of lymphocytes and plasma cells were noted (these could be tumor-infiltrating cells). The histopathologic features of the neoplastic cells (cells with multiple cytoplasmic vacuoles, characteristic of brown fat, admixed with cells containing a single large lipid droplet) were consistent with an orbital hibernoma.

Case outcome

The mass was excised about 2 weeks post-excisional biopsy results. Histopathologic examination confirmed the original diagnosis, with neoplastic ells extending to all surgical margins. A final diagnosis of an incompletely excised hibernoma was made. The patient was discharged following surgical excision of the mass and no further follow-up information was available.

Discussion

Hibernomas are benign neoplasms that arise from remnants of brown adipose tissue (BAT) and are named as such due to their resemblance to adipose tissue found in hibernating animals. Adipose tissue can be divided into two categories: white adipose tissue (WAT) and BAT. With aging, BAT is replaced by WAT, but, based on studies in rodents, it can persist in certain anatomic locations, including the interscapular, axillary or mediastinal regions.1 BAT is functionally different from WAT in that it utilizes fatty acids to generate heat while WAT metabolizes fatty acids to produce adenosine triphosphate (ATP).1 BAT contains higher numbers of mitochondria than WAT, which imparts the characteristic brown color to BAT. It also contains high amounts of a protein named thermogenin or uncoupled protein1 (UPC1), which is localized in the inner mitochondrial membrane. UCP1 is responsible for generation of heat through BAT metabolism by uncoupling of mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation from ATP synthesis.1

In veterinary species, hibernomas are mostly reported in dogs and are frequently found in the orbital and subconjunctival regions in dogs.2-4 Other reported anatomic locations include the omentum,5 nipple,6 and femoral skin,7 with the latter case report involving bilateral hibernomas. There is a single case report of an abdominal wall hibernoma in a cat,8 and a subconjunctival hibernoma in a goose.9 In addition, spontaneous hibernomas have been reported to occur in laboratory research animals, such as Sprague-Dawley rats with a reported prevalence of 3.5% based on one toxicologic study involving 1760 rats across various research facilities.10 Ravi et al., published a case series describing 7 cases of orbital hibernomas, in which most of the dogs were adults with a median age of approximately 10 years.3 In the other case reports, dogs ranged from 6 to 14 years of age.2,6,7 Similarly, in one cases of 170 human patients, hibernomas were seen in adults, although tumors were most frequently found on the thigh and trunk.11 While no sex predilection has been reported, the majority of dogs in the case series and case reports have been females, including the dog herein. No breed predilection has been reported either.

These neoplasms generally form well-demarcated masses, with characteristic cytologic features that correlate well with their histologic appearance. The lesions tend to exfoliate well for cytologic examination and smears consist of round to polygonal cells that are present individually as well as in cohesive-like groups or sheets. They have a characteristic light purple to basophilic, multivacuolated cytoplasm with fine eosinophilic granulation, as seen in this case. Nuclei are usually eccentric to paracentral with finely stippled chromatin and a single prominent nucleolus. Mitotic activity is generally minimal to absent, with mild anisocytosis and anisokaryosis. There is usually variable numbers of lipid-like vacuoles in the background and within cells.2 However, the degree of granulation can vary depending upon the morphologic variant of hibernoma. In the report of 170 human patients, hibernomas were divided into four histologic categories based on morphologic features of the cells and associated stromal changes: typical, myxoid, spindle cell, and lipoma-like variants.11 Typical hibernomas consist of three subtypes based on cell components. The most common subtype consists of pale cells with multiple cytoplasmic vacuoles (“multivacuolated”) with fewer cells containing a single lipid-like cytoplasmic vacuole, similar to that seen in our case. The next most common subtype consisted of a mixture of the multivacuolated pale cells and cells with eosinophilic granular cytoplasm. Tumors with >50% eosinophilic cells were the least common subtype of typical hibernoma and usually seen in the neck and arm. Myxoid hibernomas consist of the pale and eosinophilic vacuolated cells embedded within a myxoid background and were mostly seen in men. The spindle cell variant was the most uncommon type in the study and consisted of a mixture of spindle cells, lacking features of malignancy, with strands of collagen and interspersed groupings of pale multivacuolated cells with adipocytes. Low numbers of mast cells were also seen in this variant. Finally, the lipoma-like variant is characterized by cells with large single vacuoles (resembling a lipoma) with few pale and eosinophilic cells with multiple vacuoles.11

It is important to note that cytologic and histologic features of hibernomas can overlap with other neoplasms found in the orbital region or involving other ocular tissues, as well as other sites. In the orbital region, other neoplasms include granular cell tumors, rhabdomyoma, balloon cell melanoma, and carcinomas, such as clear cell carcinoma, meibomian or sebaceous adenocarcinoma, or lacrimal adenocarcinoma. Benign lesions, such as a xanthogranuloma, should also be considered.2 To determine tissue of origin, immunohistochemistry (IHC) for UCP1 is often utilized,1-3,6,7,12 given the high expression of UCP1 in BAT as mentioned above. Neoplastic cells would be negative for cytokeratin, helping rule out the epithelial-derived tumors. In addition, the neoplastic cells in hibernomas can express myogenic markers, such as myogenin and myoD1, which is speculated to reflect an origin from a common progenitor cell for brown adipose tissue and muscle.3 Similar staining for muscle markers is seen in liposarcomas, which originate from WAT.13 Positive IHC for muscle markers can make it difficult to differentiate lipid-based tumors from rhabdomyomas, unless IHC for UCP1 is also performed (expected to be negative in muscle tumors). Other IHC markers used in human patients include S100, which is frequently positive, and CD34, which can be expressed in spindle cell variants of the tumor.11,14,15 CD10 has also been recently explored as a potential marker in human patients.16 These additional markers are yet to be investigated in veterinary medicine; they may prove useful for supporting a diagnosis of hibernoma in cases with overlapping histologic features with the other tumors listed above.

In the present case, initial cytologic findings were concerning for malignant neoplasia, given the cytologic atypia (e.g., binucleation with intracellular anisokaryosis) and imaging findings (i.e., the mass appeared to originate from the medial left eye and extended back into the orbital region and was connected via a stalk to the medial rectus muscle). IHC with UCP1 was recommended but is not performed at our institution, hence a lipid-rich rhabdomyoma cannot be conclusively ruled out. This case highlights the importance of having hibernoma, a rare tumor, as a differential diagnosis for a subconjuctival mass because many of the tumors in this location can be malignant or highly invasive. In addition, it highlights the importance of histopathologic examination of neoplasms that may have overlapping features on cytologic examination and are difficult to conclusively identify.

Author: J Kaur (resident); edited by T Stokol.

References

- Oelkrug R, Polymeropoulos ET, Jastroch M. Brown adipose tissue: physiological function and evolutionary significance. J Comp Physiol B. 2015;185(6):587-606.

- Piccione J, Dial SM. Cytologic appearance of hibernoma in two dogs. Vet Clin Pathol. 2020;49(1):125-129.

- Ravi M, Schobert CS, Kiupel M, Dubielzig RR. Clinical, morphologic, and immunohistochemical features of canine orbital hibernomas. Vet Pathol. 2014;51(3):563-568.

- Stuckey JA, Rankin AJ, Romkes G, Slack J, Kiupel M, Dubielzig RR. Subconjunctival hibernoma in a dog. Vet Ophthalmol. 2015;18(1):78-82.

- Ochoa R. Hibernoma in a dog. Report of a case. Cornell Vet. 1972;62(1):137-144.

- Amorim I, Faria F, Taulescu M, Taulescu C, Gärtner F. Nipple Hibernoma in a Dog: A Case Report With Literature Review. Front Vet Sci. 2021;8:627288.

- Hifumi T, Inokuchi Y, Tsujio M, Tanaka S, Hirano S, Miyoshi N. Bilateral hibernomas in the femoral regions of a dog. Can Vet J. 2024;65(4):367-370.

- Ozturk-Gurgen, H., Egeden, E., Calp-Egeden, O., & Gürel, A. (2020). Abdominal Wall Hibernoma in a Cat: A Case Report. Kafkas Universitesi Veteriner Fakultesi Dergisi.

- Murphy CJ, Bellhorn RW, Buyukmihci NC. Subconjunctival hibernoma in a goose. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1986;189:1109-1110.

- Bruner RH, Novilla MN, Picut CA, et al. Spontaneous hibernomas inSprague-Dawley rats. Toxicol Pathol. 2009;37:547-552.

- Furlong MA, Fanburg-Smith JC, Miettinen M. The morphologic spectrum of hibernoma: a clinicopathologic study of 170 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25(6):809-814.

- Zancanaro C, Pelosi G, Accordini C, Balercia G, Sbabo L, Cinti S. Immunohistochemical identification of the uncoupling protein in human hibernoma. Biol Cell. 1994;80(1):75-78.

- LaDouceur EEB, Stevens SE, Wood J, Reilly CM. Immunoreactivityof canine liposarcoma to muscle and brown adipose antigens. VetPathol. 2017;54:885-891.

- Huang, C., Zhang, L., Hu, X., Liu, Q., Qu, W., & Li, R. (2021). Femoral nerve compression caused by a hibernoma in the right thigh: a case report and literature review. BMC surgery, 21(1), 30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-020-01040-y

- Suster S, Fisher C. Immunoreactivity for the human hematopoietic progenitor cell antigen (CD34) in lipomatous tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21(2):195–200.

- Gjorgova-Gjeorgjievski S, Fritchie K, Folpe AL. CD10 (neprilysin) expression: a potential adjunct in the distinction of hibernoma from morphologic mimics. Hum Pathol. 2021;110:12-19.