Interpretation

Histiocytic sarcoma

Explanation

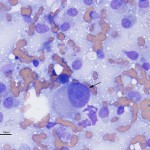

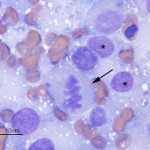

The aspirate was highly cellular, consisting of large numbers of discrete cells and red blood cells on a proteinaceous background. The round cell population had round to irregular to indented eccentric nuclei and a moderate amount of light blue pink to purple cytoplasm, containing low numbers of discrete margined vacuoles. The cells displayed several criteria of malignancy, including marked anisocytosis (variation in cell size), marked anisokaryosis (variation in nuclear size), variably sized and shaped nucleoli, abnormal mitotic figures and macronucleoli (see images below). The cytologic diagnosis was a malignant round cell tumor.

The cytologic category of round or discrete cell tumor is a term that is applied to tumors that exfoliate as individual (discrete) cells, which are generally round in shape. This category includes mast cell tumor, plasmacytoma, transmissible venereal tumor, lymphoma and the histiocytic tumors (histiocytoma and histiocytic sarcoma), but is not limited to these particular tumors. Neoplasms of mesenchymal, epithelial or neural crest origin can also exfoliate as individualized round cells in cytologic samples, including osteosarcoma, various carcinomas and primitive neuroectodermal tumors. Due to the pleomorphic nuclei, abundant light pink/purple cytoplasm and cytologic criteria of malignancy of the cells (see images below), the favored cytologic diagnosis in this case was a histiocytic sarcoma. Other differential diagnoses included lymphoma, extramedullary plasmacytoma and osteosarcoma, but these were considered less likely based on cytologic features and clinical findings – the amount of cytoplasm was larger than typical for lymphoma; the indistinct cell borders, lack of perinuclear clear zones and light pink/purple cytoplasm color were not characteristic of a plasmacytoma (these are also usually dermal versus subcutaneous masses); similarly, the lack of perinuclear clear zones, light purple cytoplasm and pleomorphic nuclei were not typical for an osteosarcoma (although these can rarely metastasize to skin or occur as primary extraskeletal tumors, they usually produce osteolytic and osteoproductive bone lesions and there was no evidence of bone involvement in this case).

|

|

|

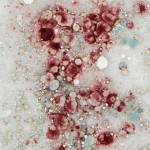

To confirm the cytologic diagnosis, a cytochemical stain – α-naphthyl butyrate esterase (ANBE) – was applied to unstained aspirate smears of the mass. This stain detects the presence of intracellular esterase enzymes; these enzymes are present in cells of dendritic or monocytic origin. All of the cells displayed diffuse cytoplasmic staining for ANBE activity, confirming a diagnosis of histiocytic sarcoma (note, we also performed a cytochemical stain for alkaline phosphatase activity, a marker of osteoblasts, and the cells were negative for this enzyme).

Discussion

Histiocytic sarcoma is part of a spectrum of several histiocytic diseases in the dog, which are derived from dendritic cells, the professional antigen presenting cells in the innate immune system1. There are various types of dendritic cells, including long-lived tissue resident dendritic cells such as epidermal (Langerhans), interstitial, and interdigitating (in peripheral lymphoid organs) cells and short-lived cells, the inflammatory dendritic cells2. Dendritic cells originate from a common myeloid/dendritic progenitor in the bone marrow, which gives rise to monocytes and tissue resident dendritic cells. Monocytes can differentiate into tissue macrophages or inflammatory dendritic cells, given the right stimuli (e.g. inflammatory cytokines for the latter cells)2. Histiocytic diseases in the dog are thought to arise from tissue resident dendritic cells or monocyte-derived macrophages1,3-5 and include the following:

- Cutaneous histiocytoma – This consists of a localized proliferation of epidermal dendritic cells (Langerhans cell). It is usually a benign, solitary lesion on the head and limbs of young dogs, but can occur in other locations and in any age of dog. These lesions usually spontaneously regress over time; regression is associated with an infiltrate of cytotoxic T lymphocytes. The tumor is comprised of discrete round cells with eccentric round to indented nuclei and a moderate amount of light blue cytoplasm. The cells usually lack cytologic criteria of malignancy and are frequently accompanied by tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes.

- Cutaneous histiocytosis – This disorder is associated with the formation of single or multiple cutaneous nodules consisting of a reactive proliferation of activated interstitial dendritic cells, commonly affecting the head and neck. Cells are typically more bland in appearance than histiocytic sarcoma.

- Systemic histiocytosis – This disorder represents a systemic version of cutaneous histiocytosis, i.e. the reactive proliferation of interstitial dendritic cells in multiple organs.

- Histiocytic sarcoma (HS) – This is a malignant neoplasm of histiocytic cells, that usually originates from various tissue dendritic cells. It can arise as a solitary lesion in many sites (e.g. central nervous system, joints, skin, spleen) and is highly aggressive, metastasizing widely.1,3 Hemophagocytic histiocytic sarcoma is a recognized subset of disseminated HS that appears to originate from splenic or bone marrow macrophages and typically infiltrates the bone marrow, liver and spleen. The cells display marked erythrophagocytic activity, resulting in an moderate to severe anemia, that is usually regenerative. Low numbers of spherocytes may be seen, but Coombs testing (for complement C3 or antibody on red blood cells) is usually negative.6 Histiocytic sarcomas are typically encountered in middle-aged large breed dogs, including Bernese mountain dogs, rottweilers, labrador retrievers, flat-coated retrievers and golden retrievers, but can be seen in any breed.1,3-5 Cytologically, lesions are characterized by a dense population of pleomorphic round cells displaying criteria of malignancy, including bi- and multinucleated cells. They usually have moderate to abundant amounts of vacuolated cytoplasm. Some more spindled variants may be seen. Positive cytochemical staining for ANBE aids in the cytological diagnosis, although more specific immunostains for dendritic lineage markers can also be applied to cytology smears, including CD1c, CD11c, and CD11d. On histopathologic examination, the tumor consists of large numbers of large, frequently vacuolated round cells. At Cornell University, the diagnosis is confirmed on formalin-fixed sections by immunostaining for CD18 (other more specific histiocytic markers are destroyed by formalin fixation), although other markers, such as lysozyme and BLA-36, can also be used for this purpose. Although CD18 is a general leukocyte marker (it stains all leukocytes), histiocytic sarcomas stain strongly positive, whereas other leukocytes are weakly positive or negative, for this cell-surface protein in formalin-fixed sections. Treatment of localized HS involves local control of the tumor via surgical excision and/or radiation, followed by systemic control with chemotherapeutic agents, most notably CCNU (lomustine).7 Due to the aggressive nature of the disease, median survival time with treatment is three to six months. Thus, histiocytic sarcoma carries a poor prognosis.

Further information and follow up

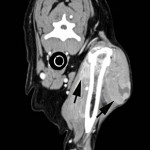

A CT scan was performed to determine the margins of the mass. A locally extensive, contrast-enhancing mass was observed lateral to the left humerus (margins delineated by arrows in figure on the right) extending medial to, but not invading into, the humerus and scapula (scapula not shown). Additionally, a soft tissue mass was observed at the level of the thyroid gland (not shown). This mass was not biopsied, but incisional biopsy was performed on the shoulder mass; histopathology confirmed the cytologic diagnosis of histiocytic sarcoma via immunohistochemistry (CD18+). A primary thyroid or parathyroid tumor was suspected, but not confirmed, as the cause of the mass in the thyroid region.

The mild increase in creatinine, despite the normal urea nitrogen, likely indicated decreased glomerular filtration rate, perhaps as a consequence of hypercalcemia-induced renal injury. The mild proteinuria (which may be excessive for the urine specific gravity) was not pursued further (with a urine protein to creatinine ratio) but could reflect glomerular or tubular injury. The high alkaline phosphatase (ALP) was attributed to endogenous corticosteroids (stress), since dogs have a steroid-inducible isoform of ALP. The ionized hypercalcemia could have been related to an underlying parathyroid tumor (if this was the cause of the mass in the region of the thyroid) or the histocytic sarcoma (the mild renal dysfunction was ruled down as a cause for the hypercalcemia). There have been isolated reports of hypercalcemia in dogs with histiocytic sarcoma, although a direct link to the tumor has not been established. Measuring serum levels of PTH, PTH-related protein and vitamin D would have been helpful in elucidating the cause of the hypercalcemia. It is interesting that the hypercalcemia resolved with chemotherapy (see below), suggesting that it may be a paraneoplastic phenomenon with this tumor. The biochemical abnormalities in this dog’s serum are not specific or characteristic of histocytic sarcoma. The most common biochemical changes reported with the tumors, particularly the hemophagocytic variant, are hypoalbuminemia and hypocholesterolemia6 (neither of which this dog had).

Due to the locally invasive nature of the mass, amputation was offered as a treatment option but chemotherapy was pursued instead. The patient received two doses of oral CCNU but this treatment was discontinued due to myelosuppression (neutropenia) and palliative treatment with prednisolone and pregabalin and tramadol for pain relief was begun. Five months later, the patient presented with a subcutaneous mass in the inguinal region. Excisional biopsy was performed and histopathology revealed histiocytic sarcoma. Further staging and chemotherapy were declined but palliative therapy was continued. The last follow-up with the referring veterinarian indicated that the dog has defied the odds and is still alive (1.4 years after initial diagnosis)!!

References

- UC Davis Website – Canine histiocytosis

- Auffrey C et al (2009) Blood monocytes: Development, heterogeneity, and relationshiop with dendritic cells. Ann Rev Immunol 27:669-692.Affolter, VK, PF Moore (2002) Localized and disseminated histiocytic sarcoma of dendritic cell origin in dogs. Vet Pathol 39:74-88.

- Fidel, J et al (2006) Histiocytic sarcomas in flat-coated retrievers: a summary of 37 cases (November 1998-March 2005). Vet Comp Oncol 4:63-74.

- Fulmer, AK, Mauldin GE (2007). Canine histiocytic neoplasia: An Overview. Can Vet J 48: 1041-1050.

- Moore PF, Affolter VK, Vernau W (2006). Canine hemophagocytic histiocytic sarcoma: A proliferative disorder of CD11d+ macrophages. Vet Pathol 43: 632-645.

- Skorupski, KA et al (2009). Long-term survival in dogs with localized histiocytic sarcoma treated with CCNU as an adjuvant to local therapy. Vet Comp Oncol 7: 139-144.