Interpretation

Carcinoma with necrosis and mixed inflammation.

Explanation

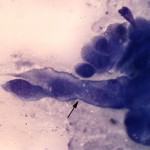

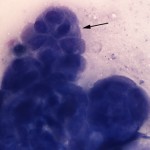

The cytologic smears consisted of large amounts of necrotic debris with low numbers of neutrophils and macrophages along with a few intact individual and clusters of moderately pleomorphic epithelial cells (Figures 1 and 2). The epithelial cells were found in papillary to trabecular arrangements (Figure 3). Cells were cuboidal to polyhedral in shape with moderate to high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratios and basophilic cytoplasm. Nuclei were ovoid with stippled chromatin and 1-3 variably sized nucleoli. Anisocytosis and anisokaryosis were moderate with rare macronuclei and macronucleoli noted. Given that the kidney was the only organ determined to be involved in the neoplastic process, the mass was considered to be of primary renal origin, arising from either the proximal or distal renal tubular epithelial cells (question 2).

|

|

|

Discussion

Neoplasia of the kidney is uncommon and represents 0.5-1.7% of all neoplasms in dogs.1,2 Lymphoma is the most common renal neoplasm, followed by primary renal carcinomas and hemangiosarcomas (question 1). The treatment and prognosis are vastly different across these major groups of tumors and fine-needle aspiration can aid in deciding the appropriate course of action (question 3). Lymphoma often presents bilaterally, with additional organ/node involvement, and is more responsive to chemotherapy. Dogs with renal hemangiosarcomas have improved survival rates and lower incidence of distant metastasis at diagnosis compared to dogs with hemangiosarcomas involving other visceral organs (splenic, cardiac and retroperitoneal).3 Renal carcinomas can arise from the epithelial cells of the proximal tubules, distal tubules, or collecting ducts. Primary renal carcinomas are typically located in the pole of the kidney, whereas other renal epithelial tumors (transitional cell carcinomas) tend to be found in the renal pelvis.4 More than 90% of primary renal tumors in companion species are malignant and the majority are carcinomas.5 Studies in dogs have not identified a difference in prognosis between the various tumors arising from these different types of epithelial cells and both are treated with surgical excision (question 3).5

Histologically, renal carcinomas are divided into clear cell, chromophobe, papillary, and multilocular cystic renal cell carcinomas. Clear cell morphology is associated with increased survival times. Studies have shown that mitotic index is an independent prognostic variable in primary renal carcinomas.6 Retrospective analyses have shown that hematuria, pyuria, proteinuria and isothenuria are common findings in dogs with renal carcinomas.7 Paraneoplastic leukocytosis and polycythemia (an increase in total red blood cell mass) have both been documented in dogs with this type of tumor.8,9 Leukocytosis has been attributed to production of colony-stimulating factors (specifically GM-CSF) by the tumor cells.8 The underlying mechanism driving polycythemia is hypoxia and subsequent production of erythropoietin. Local hypoxia due to compression is thought to contribute.9 Mutations in the tumor suppressor protein von hippel landau have been documented to drive both the molecular events that drive renal carcinoma development, as well as polycythemia in people with renal carcinomas.10 At this time, it is unknown if this pathway contributes to disease pathogenesis in the dog.

Further Information

Before the cytologic smears were evaluated, the patient underwent a computerized tomography scan which revealed a large (5 cm diameter) multi-lobulated, heterogeneous mass that projected ventrally from the left kidney. Portions of the mass appeared fluid-filled and other parts were mineralized. The left renal lymph nodes were mildly larger than normal (0.4-0.5 cm diameter) and increased in number. The gall bladder contained a small amount of dependent, mineral-attenuating sediment. Caudal to both kidneys and adjacent to the urinary bladder were small, mineral-attenuating nodules. Both lungs contained approximately 10 small (up to 0.3 cm diameter) well-margined soft-tissue nodules and a few tiny (up to 0.1 cm diameter) mineral nodules. Consultations with Soft Tissue Surgery and Medical Oncology services were provided. The patient was discharged to the owners for consideration of further treatment options. Because of the poor prognosis, as well as the associated pain and the long recovery times associated with surgical nephrectomy and chemotherapy, the owners did not pursue aggressive treatment. Without treatment, the patient’s estimated survival time was 3-12 months.

References

- Bartges and Osborne, in Osborne and Finco: Canine and Feline Nephrology and Urology. Lea & Febiger, Philadelphia, PA, 1995. pp 277-303.

- Meinkoth, Cowell, and Tyler, in Diagnostic Cytology and Hematology of the Dog and Cat: The Renal Parenchyma. Mosby, Inc. St. Louis, MO, 1999. pp 203-2073.

- Locke JE, Barber LG. Comparative aspects and clinical outcomes of canine renal hemangiosarcoma. J Vet Intern Med. 2006 Jul-Aug;20:962-7.

- Militerno G, Bazzo R, Bevilacqua D, Bettini G, Marcato PS. Transitional cell carcinoma of the renal pelvis in two dogs. J Vet Med A Physiol Pathol Clin Med. 2003 Nov;50:457-9.

- Withrow, in Withrow and MacEwen: Small animal clinical oncology. Saunders, Philadelphia, PA, 1989. pp 380-385.

- Edmondson EF, Hess AM, Powers BE. Prognostic Significance of Histologic Features in Canine Renal Cell Carcinomas: 70 Nephrectomies. Vet Pathol. 2014 May 14. [Epub ahead of print].

- Bryan JN, Henry CJ, Turnquist SE, Tyler JW, Liptak JM, Rizzo SA, Sfiligoi G, Steinberg SJ, Smith AN, Jackson T. Primary renal neoplasia of dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2006; 20:1155-60.

- Petterino C, Luzio E, Baracchini L, Ferrari A, Ratto A. Paraneoplastic leukocytosis in a dog with a renal carcinoma. Vet Clin Pathol. 2011 Mar;40:89-94.

- Crow SE, Allen DP, Murphy CJ, Culbertson R Concurrent renal adenocarcinoma and polycythemia in a dog. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 1995 Jan-Feb;31:29-33.

- Rad FH, Ulusakarya A, Gad S, Sibony M, Juin F, Richard S, Machover D, Uzan G. Novel somatic mutations of the VHL gene in an erythropoietin-producing renal carcinoma associated with secondary polycythemia and elevated circulating endothelial progenitor cells. Am J Hematol. 2008 Feb;83:155-8.

Authors: E Behling-Kelly, R Dudis (Class of 2014), T Stokol