Babesia and Theileria are protozoal parasites that are different genuses within the phylum Apicomplexa. They have a replicative stage within mammalian RBCs. Since one of the life stages (sporozoites) replicate asexually (to form merozoites) within RBCs and rupture RBCs to infect other cells, they result in a hemolytic anemia with an intravascular component (hemoglobinemia, hemoglobinuria), helping to distinguish infections clinically from Anaplasma species. Although within the same phylum, Theileria is distinguished from Babesia by the presence of an extra-RBC phase (in blood leukocytes) and molecular methods, including 16S ribosomal RNA sequencing and analysis of immunodominant equine merozoite antigen (EMA) gene sequence (Kappmeyer et al 2012).

The organism is tick-borne and sporozoites are transmitted by the saliva in the tick bite. Various ticks, including Ixodiae (e.g. Dermacentor, Rhipicephalus, Amblyomma) and Argasidae (e.g. Ornithodorus) species, can transmit the organisms. Once within the blood, sporozoites invade RBC and multiply asexually forming trophozoites and merozoites. Theileria species can invade other cells (blood leukocytes) forming schizonts, which release sporozoites in the infected host. Sexual reproduction can occur in blood (forming gametocytes) but this usually occurs within the tick intestinal tract after the tick has ingested blood containing merozoites. Release of merozoites ruptures RBCs, causing intravascular hemolysis and both parasitized and non-parasitized organisms are removed by splenic macrophages as well (extravascular hemolysis). The organisms can also cause microthrombi by aggregating within blood vessels and are associated with coagulation abnormalities, such as disseminated intravascular coagulation in some affected patients (Goddard et al 2013, Wise et al 2013). After infection, animals frequently become asymptomatic carriers with disease recrudescence occurring in times of stress or after splenectomy.

Dogs

Dogs can be infected with various Babesia organisms. Most of the parasites belong to Babesia sensu stricto genus, which includes large organisms, such as B. canis, B. rossi and B. vogeli and the smaller organisms, B. gibsoni. New species of Babesia continue to be identified and organisms typically found in other animal species, such as B. vulpes in foxes, have also been discovered in dogs (Barash et al 2019, Baneth et al 2020). The different Babesia are carried by various ticks (e.g. Rhipicephalus sp., Ornithodorus sp.) and dual or multiple infections with other tick-borne organisms, such as Mycoplasma, Hepatozoon, Borrelia and Ehlrichia species, can be seen (Barash et al 2019, Baneth et al 2020). Common hematologic findings in infected dogs include anemia and thrombocytopenia or low normal platelet counts.

Babesia canis

Transmission is primarily by the brown dog tick (Rhipicephalus sp.). Infection can result in inapparent, mild or severe disease, depending to some extent on the pathogenicity of the infecting strain and the susceptibility of the host. Puppies are more likely to be severely affected than adult dogs. Mild disease is mainly an extravascular hemolytic anemia but severely affected dogs have signs of intravascular hemolysis (as the parasite lyses the red blood cell to complete its lifecycle) and may develop disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). In general, the parasite induces a concurrent Coombs positive immune-mediated hemolytic anemia. A hyperacute syndrome producing hypotensive shock has been seen in some dogs, and also occurs with B. bovis in cattle. This is thought to be due to liberation of kallikrein (a potent vasodilator) and is usually associated with low parasite numbers. Some dogs have a chronic syndrome of anemia and fever with lymphoid hyperplasia and lymphocytosis; circulating parasitemia is very difficult to detect in chronic cases and requires PCR testing for confirming the diagnosis.

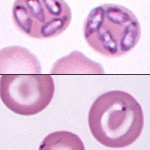

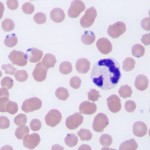

Definitive diagnosis is based upon finding the organisms in red blood cells or a positive PCR result, which has replaced less sensitive immunologic-based tests. B. canis appear usually as single or multiple (pairs or tetrads, in so-called Maltese cross formations) large organisms in the red blood cells in smears. Red blood cells containing Babesia organisms have a density similar to that of reticulocytes, and therefore, are concentrated just below the leukocytes in a centrifuged microhematocrit tube. Low-grade parasitemia is more easily detected by examination of a buffy coat smear prepared from blood collected from small peripheral vessels, such as in the ear, than a blood smear made from a central vein (e.g. jugular vein). Babesia organisms are removed from peripheral red blood cells in the spleen, resulting in asymptomatic carriers. Before the advent of PCR testing, Greyhound blood donors used to splenectomized or treated with immunosuppressive doses of corticosteroids to detect subclinical infections. Greyhounds used to have a high prevalence of Babesia infections.

Babesia gibsoni

In comparison to Babesia canis, this organism is much smaller and forms rings with a dark nucleus on one side in the red blood cell. They can be readily missed on cursory blood smear examination.

Cats

Babesia felis is a rare parasite that can produce a regenerative anemia, lethargy and anorexia in cats. The parasite is very small and quite difficult to visualize. Affected cats can be icteric and hyperglobulinemic.

Horses

Two species infect horses, donkeys and mules: Theileria equi and Babesia caballi. Dual infections can be seen. Infection with these agents has been reviewed (Wise et al 2013). These infectious organisms are endemic in Asia, southern Europe, south and central America and Africa. They are reportable diseases in the USA, with outbreaks occurring in horses usually in southern states, presumably due to introduction of infected carriers from endemic countries. As stated above, Theileria equi (which used to be called Babesia equi) has an extra-RBC phase in blood leukocytes, with the organism forming schizonts which release sporozoites which infect RBCs. The two organisms can also be distinguished by their morphologic appearance in peripheral blood. Babesia equi is usually seen as two pear-shaped (pyriform) organisms in blood, whereas 4 pyriform organisms are typically seen in infected red blood cells, forming a “Maltese cross” with Theileria equi. However, identification of the organisms in blood is an insensitive (although specific) diagnostic tool. Theileria equi tends to be more pathogenic. Transmission occurs between horses with ticks, through fomites, common needle usage, and transplacentally. In experimental infections, clinical signs are usually apparent within 10-30 days. Clinical signs are usually not specific, consisting of fever, anorexia, depression, lethargy and peripheral edema. Petechial hemorrhages may be seen in some horses. Renal failure can result from the intravascular hemolysis. Peracute disease resulting in death can occur. Signs in neonatal foals can mimic neonatal erythrolysis, occurring within 2-3 days of birth in foals with transplacental infection. Chronic infections result in non-specific clinical signs with a mild anemia from extravascular hemolysis. Some animals do not show signs of disease. Once infected, animals become lifelong carriers and reservoirs of infection. Clinicopathologic abnormalities include anemia (with intravascular hemolysis in severe cases), thrombocytopenia (30-100% of cases, particularly dual infections or horses infected with Babesia caballi) and hyperbilirubinemia. Increased liver enzymes may be seen (SDH, AST), likely from hypoxic injury due to anemia or microvascular thrombosis. High fibrinogen indicates concurrent inflammation and low phosphate and iron have been documented in some cases (mechanism unclear). For diagnosis, regulatory tests include competitive ELISAs, although results can remain positive in animals that have cleared infections (as assessed by transmission studies and PCR). PCR can be used for diagnosis although this is usually available only in some research laboratories. Imidocarb is the treatment of choice (Wise et al 2013).

Cattle

Babesia bigemina (Texas cattle fever) and Babesia bovis (red water fever) affect cattle. B. bovis produces more severe disease and can cause red water fever in deer. They are transmitted by Boophilus ticks. They produce a hemolytic anemia, hemoglobinuria, fever, and anorexia. The hemoglobinuria in Babesiosis distinguishes the hemolytic anemia from Anaplasmosis, which is an extravascular hemolysis. Young calves < 7 months of age are often resistant to infection. B. bovis, in particular, can induce DIC and can cause autoagglutination of red blood cells in the brain which blocks capillaries, producing cerebral babesiosis. Diagnosis is by detection of the organism in blood smears or by serology (IFA or complement fixation).

Sheep

Babesia ovis and Babesia motasi infect sheep. B. ovis produces mild disease of short duration, whereas B. motasi causes fatal disease in acute cases. Like all Babesia organisms, sheep that recover from babesiosis become asymptomatic carriers.

Cervids

Babesia odocoilei infects deer and reindeer. Infection can result in sudden death due to severe intravascular and extravascular hemolysis. Numerous organisms are typically seen in blood smears from infected animals.