This non-traditional approach to acid-base assessment involves consideration of strong ions and the effects of proteins on acid-base status. The strong ion approach is quite complicated and uses many formulas, which are beyond the scope of this content. However, this approach can be very useful because it is:

- More physiologic than the traditional way of assessing acid-base status and

- Optimal for determining the best treatment for acid-base abnormalities.

Advantages of the strong ion approach for diagnosis of acid-base disturbances are nicely outlined by Constable (2014), who also provides relevant equations, pertinent to cattle.

The main points about the strong ion approach that will be addressed here are general principles, the strong ion difference, and different types of acid-base disturbances identified by this approach. At Cornell University, we use a combination of the classic blood-gas interpretation (pH, bicarbonate and base excess = metabolic, pCO2 = respiratory) and strong ion approach, particularly with respect to strong ions (measured electrolytes and unmeasured, e.g. lactate).

General principles

- Electroneutrality must be maintained.

- Acid-base status is primarily determined by the lungs (which alter pCO2) and kidneys (which alter strong ions).

- There are independent (altered by processes outside the body) and dependent (affected by internal changes or independent variables) variables.

- Independent variables:

- pCO2: Altered by alveolar ventilation. Interpreted as standard approach.

- Strong ions: These are fully dissociated at a normal pH and exert no buffering effect. They include Na+, K+, Cl–, Ca2+, Mg2+, and organic acids, e.g. β-hydroxybutyrate, lactate. Na+ and Cl– concentrations are particularly affected by renal excretion and absorption. The influence of these strong ions on the pH and HCO3– is expressed as the strong ion difference (SID) and BE.

- Nonvolatile weak acids (or Atot): These acids that are not fully dissociated at physiologic pH and include proteins and phosphate.

- Dependent variables: These are interpreted as for the traditional approach.

- HCO3–

- H+

- Independent variables:

Strong ion tests

Strong ion difference (SID)

The strong ion difference is the difference between positively (cations) and negatively (anions) charged strong ions (cations – anions). It is relatively simple to calculate the SID(inorganic) from Na+ and K+ and Cl–, as follows:

SID(inorganic) = Na+ + K+ + H+ = Cl– + OH–,

rearranging this yields:

SID(inorganic) = (Na++ K+) – Cl– = OH–– H+.

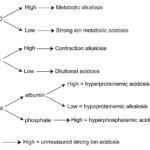

- High SID = strong ion alkalosis (increased OH– or decreased H+) and is due to loss of a chloride-containing acid (metabolic alkalosis) or gain of sodium in excess of chloride.

- Low SID = strong ion acidosis (decreased OH– or increased H+) and is due to gain of a chloride-containing acid or loss of sodium in excess of chloride.

Even though sodium and chloride are the dominant strong ions in plasma, most authors use K+ in the equation above (Constable 2014, Krump et al 2021). You do not correct the chloride when using this equation. We have found that the SID with the above equation is a better predictor of acid-base status than Na+-Cl– alone. Below are reference intervals we have established in our laboratory for strong ion difference using the above equation.

| Species | Strong ion difference reference interval (mEq/L) (Na+ + K+) – Cl– |

| Dogs | 36.7-46.5 |

| Cats | 33.3-44.9 |

| Horses | 38.8-46.3 |

| Cattle (Holstein) | 44.4-51.7 |

| Sheep | 41.9-54.8 |

| Goats | 36.6-46.4 |

| Donkeys | 34.0-45.3 |

| Alpaca | 37.7-48.5 |

| High strong ion difference | Metabolic alkalosis (loss of a chloride-containing acid) |

| Low strong ion difference | Metabolic acidosis (gain of a chloride-containing acid or loss of bicarbonate) |

The SID, as calculated above, does not detect unmeasured strong anions (XA‑, e.g. lactate, sulfates, phosphates) that would cause a titration metabolic acidosis. However, the contribution of these unmeasured strong ions can be taken into account with other formulae, e.g. calculating the unmeasured strong ion concentration [XA–] or the strong ion gap (similar to the AG). Therefore, the SID must be interpreted in conjunction with the AG or [XA–], i.e. a normal SID but a high AG or [XA–] indicates a titration metabolic acidosis. Note, that you may come across a calculation of SID which includes lactate as part of the negatively charged ions, i.e. (Na+ + K+) – (Cl– + lactate–) and even free ionized calcium or magnesium on the positive side of the equation (Fettig et al 2012, Gomez et al 2013, Viu et al 2017, Gärtner et al 2019). This variation adds confusion to interpretation and makes it impossible to compare between studies or use normal ranges that are in the literature (hence we have provided ours above).

Weak acids (Atot)

This includes phosphate and proteins, particularly albumin, which are weak anions (or acids). Renal or respiratory compensatory mechanisms do not occur in response to changes in Atot.

- High Atot = hyperphosphatemic acidosis or hyperproteinemic acidosis. An increase in protein, particularly albumin (e.g. dehydration) will result in a mild decrease in pH.

- Low Atot = hypoproteinemic alkalosis. A decrease in albumin will result in an increase in pH.

Unmeasured strong ions [XA–]

Unmeasured strong ions include lactate, ketones (β-hydroxybutyrate, acetoacetate), and sulfates. The presence of these XA– can be evaluated using several formulae, only one of which will be given here. In this formula, [XA–] is estimated by their contribution to the base excess (BE); since XA– are anions, they will cause an acidosis and decrease the BE.

[XA–] = BE – (change in albumin + change in phosphate + change in water + Cl–),

where, change is the difference between the midpoint of the reference interval and the measured concentration of the specific analyte. The change in free water uses a formula involving sodium concentrations and the normal strong ion difference. Hence, this just adds complexity to the analysis.

- High [XA–] = metabolic acidosis due to an increase in unmeasured strong ions.

Other investigators use different formula for assessing unmeasured anions, e.g. (Na+ + K+ + Ca2+ + Mg2+) – (Cl– + phosphate + albumin charge + globulin charge) (Gärtner et al 2019).

Strong ion gap

Calculation of the strong ion gap (SIG; do not confuse with a strong ion difference) is another way to evaluate for the presence of unmeasured strong anions (acids), such as lactate and ketones. There are two formulae, which use the standard anion gap ([Na+ + K+] – [Cl– + HCO3–]) and either albumin or the total protein concentration for the calculation. These formulas also require pH. For example, these formulae have been used in cattle (Constable 2014) (they are essentially the same equation with a different correction factor and use a pKa [acid dissociation constant] of 7.08 for weak acids):

Strong ion gapalbumin = albumin x (0.622 ÷ [1 + 107.08 – pH]) – anion gap

Strong ion gaptotal protein = total protein x (0.343 ÷ [1 + 107.08 – pH]) – anion gap

Other investigators do not use the correction factor (Gärtner et al 2019) or different formulae entirely to calculate the strong ion gap (Fettig et al 2012), which makes it difficult to compare between studies.

Summary of strong ion approach

The strong ion approach can identify a metabolic alkalosis and acidosis (see table below) and is superior to the traditional method of assessing acid-base status by inclusion of strong ions (which are critical for the interpretation of acid-base status) and proteins, which are not usually assessed with the traditional approach, which only examines pH, pCO2, base excess, and the dependent variable of bicarbonate.

| Disturbance | pCO2 | SID | Atot | [XA–] |

| Strong ion acidosis | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ |

| Strong ion alkalosis | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ |