Interpretation

Peritoneal fluid: Eosinophil-rich low protein transudate

Pleural fluid: Low protein transudate with an increased proportion of eosinophils

Esophageal nodule: Aberrant presence of gastric mucosa

Explanation

The peritoneal fluid can be classified as an eosinophil-rich low protein transudate (Question 1). Low protein transudates in the abdominal cavity are due to alterations in hydrodynamic forces, such as decreased oncotic pressure or presinusoidal hypertension or both, with hypertension typically affecting intestinal or mesenteric lymphatic vessels. Both scenarios were likely occurring in this dog because of the marked hypoalbuminemia and relatively high proportion of lymphocytes in the peritoneal fluid.

The pleural fluid was also classified as a transudative effusion with concurrent hemorrhage or erythrodiapedesis (Question 1). The proportion of eosinophils was higher than typically seen in such effusions (usually <2% in our experience). The effusion was likely due to a combination of hypoalbuminemia and lymphatic or venous hypertension, given the evidence of hemorrhage or erythrodiapedesis in the smears of the fluid. Based on the intestinal lesions identified in the abdominal ultrasonographic examination and panhypoproteinemia, intestinal disease was prioritized as the cause of the dog’s effusions, such as inflammatory bowel disease (potentially eosinophilic, given the high proportion of eosinophils in the peritoneal fluid and phagocytosis of eosinophils by macrophages), lymphangiectasia, or congenital intestinal disorders, considering the young age of the dog (Question 2). Underlying infections, such as parasites or fungi, could not be ruled out.

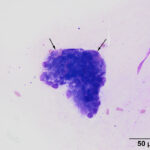

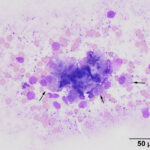

The direct smears of the aspirate of the esophageal nodules revealed clusters of mucinous epithelial cells embedded within mucus (Figures 2-3). In addition, individual epithelial cells within clusters of cuboidal cells had eccentric nuclei and numerous pink granules, resembling parietal cells from the gastric mucosa (Figures 4-5). Mucinous columnar epithelium, as seen in the stomach, is found in the distal 1-2 cm of the esophageal mucosa as the esophagus transitions into the stomach. However, the mid-esophagus is lined by non-keratinized stratified squamous epithelium.1 Thus, the presence of mucinous columnar epithelial and parietal cells were an unexpected finding for an aspirate from this region of the esophagus (Question 3). In addition, clusters of cuboidal cells with blue granules in the cytoplasm, presumptive chief cells, were also seen in the aspirate smears (Figure 5). The main differential diagnosis for the cytologic results was heterotopic gastric mucosa of the esophagus.2 Metaplasia of the esophageal mucosa from acid reflux was an alternative diagnosis but considered less likely based on the more proximal location of the lesions and the otherwise normal appearing esophageal mucosa. These esophageal would not explain the effusions or the panhypoproteinemia (Question 4).

|

|

|

The hypocholesterolemia was attributed to decreased absorption from the intestine and can be seen in over 50% of dogs with protein-losing enteropathy.3,4 The mild hypomagnesemia could be explained by loss (or lack of absorption) via the intestinal tract or the low albumin concentration (given that 33% of magnesium is albumin-bound). The lack of concurrent hypocalcemia was a surprising finding that is difficult to explain. The decreased iron concentration and total iron binding capacity is a pattern typical of inflammation of several days duration, however the low iron concentration could be due to transient random variation and the low total iron binding capacity due to loss of transferrin with albumin into the intestine. The mild hyperglycemia can be explained by a stress (endogenous corticosteroid) or epinephrine response.

Additional tests

Unfortunately, endoscopic biopsies of the lesions in the esophagus were attempted, but unfortunately were not successful due to the firm nature of the lesions. Biopsies of the stomach and duodenum were taken and submitted for histopathologic examination. While waiting for the results, testing for specific infectious organisms, including an antigen test for Blastomyces species (due to the pulmonary signs), a fecal DNA test for Heterobilharzia americana (due to the eosinophil-rich abdominal effusion) and a sugar and zinc sulfate flotation for Spirocerca lupi (to potentially explain the nodular lesions in the esophagus) were negative. Since hypoadrenocorticism can cause hypocholesterolemia and a protein-losing enteropathy in dogs,5 ACTH stimulation testing was done. The pre- and post-ACTH stimulation cortisol concentrations were normal, ruling out hypoadrenocorticism. Vitamin B12 concentrations were increased (1082 pg/mL, RI: 175-800 pg/mL), which is unexpected in a dog with diffuse small intestinal disease and protein-losing enteropathy (cobalamin concentrations are frequently decreased4). However, hypercobalaminemia has been reported in dogs with gastrointestinal and other diseases, including one dog with protein-losing enteropathy. The mechanism for the increase is unclear (it was speculated to be due to alterations in gastrointestinal flora or increased absorption as a consequence of a disrupted mucosal barrier).6 In addition, serum cobalamin is not the most accurate representation of intracellular cobalamin levels, i.e. serum cobalamin levels can be normal with true cobalamin deficiency.

On histologic examination of the biopsies, mild superficial mucosal edema was identified in the stomach. In the intestine, there was moderate diffuse lymphoplasmacytic inflammation in the lamina propria with villous blunting and a paucity of intestinal lacteals. Lymphocytes were seen within the intestinal mucosa and eosinophils were also part of the inflammatory infiltrate within the lamina propria but were present in lower numbers versus the other mononuclear cells. Immunohistochemical staining for PROX-1 (a marker of lymphatic endothelium) confirmed the lack of lymphatic endothelium within the villi. In contrast, staining with von Willebrand factor (a marker of vascular endothelium) revealed normal blood vessels within the villi. Immunostaining with alpha-smooth muscle actin showed smooth muscle hypertrophy within the villi. The histologic diagnosis was small intestinal villous lymphatic hypoplasia and a moderate diffuse lymphoplasmacytic and eosinophilic enteritis. These results explained the young presenting age of the dog, and the clinicopathologic evidence of a protein-losing enteropathy, as well as the presence of eosinophils in the effusions.

Outcome

The dog was administered anti-inflammatory doses of corticosteroids and discharged to its owners with additional supportive care for gastrointestinal disease, including a hypoallergenic diet, proton pump inhibitors (omeprazole), and sucralfate. In addition, drugs to alleviate the effusions (furosemide, spironolactone) were prescribed. The dog was then lost to follow-up.

Discussion

Heterotopic gastric mucosa of the esophagus, also referred to as a heterotopic gastric mucosal patch or cervical inlet patch, refers to the aberrant presence of gastric mucosa within the esophagus.2,8,9 The lesions typically are present in the proximal esophagus, just caudal to the upper esophageal sphincter,8 but can occur at other sites within the gastrointestinal tract or gall bladder.8,10 The lesions are usually single, flat or slightly depressed, round to oval and discolored compared to the surrounding esophageal mucosa (pink versus gray) with distinct margins. They can be multiple, circumferential and nodular to multinodular to polypoid,9,10 as seen in this dog. Although they are largely considered incidental findings, the heteropic mucosa has been associated with oral symptoms, such dysphagia and sore throat, in humans. These symptoms are thought to be secondary to excess gastric acid secretion from the parietal cells within the patch.9-11 Rarely, the lesions can result in strictures, severe hemorrhage, abscesses or fistula formation, and esophageal perforation.9,12 In dogs, the condition was first uncovered incidentally on necropsy in 4% of 365 young (6-18 month old) laboratory Beagle dogs in a toxicity study. They were found as single lesions with central depressions on the mucosal side of the ileal and jejunal intestine and were thought to be congenital,13 as was likely in this case. On histologic and electron microscopic assessment, the lesions consisted of islands of gastric mucosa with mucous-secreting, chief and parietal epithelial cells, as seen in the aspirates from the esophageal nodules in the dog of this report. The gastric mucosa replaced the normal intestinal mucosa at the affected sites and differed from normal gastric mucosa by containing less mucus and tubular or ductular structures in the epithelium at the base of the crypts.13 However, there have been rare reports of clinical signs associated with heterotopic gastric mucosa in dogs. In a 7 month old dog with abdominal pain, an abscessed heterotopic gastric mucosa formed a mass-like lesion in the abdomen that was associated with the jejunum (and thought to have arisen from an intestinal diverticulum).14 In a 14 year old dog, heterotopic gastric mucosa in the jejunum formed multiple cystic hemorrhagic lesions that mimicked intestinal neoplasia and resulted in severe hemorrhage.15 In contrast to these reports, the lesions in the dog herein were in the esophagus. They were also thought to be an incidental finding, discovered upon endoscopic evaluation of the gastrointestinal tract for evaluation of a suspected enteropathy (although the incidental nature of the lesion was not known at the time of examination). Unfortunately, the esophageal lesions were too firm for endoscopic biopsies. The origin of heterotopic gastric mucosa is controversial;10 they are thought to be mostly congenital lesions,9,10 as suspected in dogs.13,14 However other posited theories are that they are acquired from rupture of the gastric submucosal glands or injury to the mucosa from acid reflux, with subsequent gastric metaplasia during regeneration of the esophagus mucosa.9,10 Gastric acid or acid plus bile contact with the esophagus causes columnar metaplasia with goblet and parietal cells in experimental studies in dogs.16 In a meta-analysis of human patients, esophageal heterotopic gastric mucosa is associated with Barret’s esophagus (gastric metaplasia of the esophagus due to chronic acid reflux) and gastritis.7 In humans and dogs, the lesions can rarely become malignant, giving rise to adenocarcinomas.9,17,18

Small intestinal lymphatic hypoplasia is a rare condition, with a single report of 3 cases to date (this dog was not included in the prior report).19 The dogs were presented with clinical signs and laboratory data consistent with a protein-losing enteropathy, including vomiting, diarrhea, inappetence, and weight loss, and panhypoproteinemia, hypomagnesemia, hypocalcemia, and hypocholesterolemia, respectively. Lack of intestinal lacteals (confirmed by PROX-1 immunostaining) and villous blunting were characteristic findings on histologic analysis of intestinal biopsies.19 The case herein was unusual in that the dog also had inflammatory bowel disease and the main reason for presentation was a bicavitary effusion with clinical signs related to the pleural effusion (although the dog was also inappetent). Pleural effusions are documented in animals with gastrointestinal disease, such as lymphangiectasia,20 and human patients with intestinal lymphatic hypoplasia,21 are largely attributed to reduced oncotic pressure from hypoalbuminemia. However, other mechanisms, such as vascular hypertension, may be at play. The pleural effusion In the dog of this report could also be explained by hypoalbuminemia, even though the albumin concentration was above the 1.0-1.5 g/dL largely used as a risk factor for effusions or edema.22 However, the actual albumin concentration may be lower than 1.8 g/dL because the bromcresol green method used for albumin measurement on chemistry analyzers, including the analyzer at Cornell University, also binds to alpha globulins and fibrinogen,23 which are increased in inflammatory states. Fibrinogen would not be a target for bromcresol binding in this case because the chemistry panel was performed on serum and not plasma. In the three published cases of intestinal lymphatic hypoplasia, ascites was documented in 2 dogs. Unfortunately, the prognosis in this rare condition is poor, with all 3 dogs being euthanized due to progressive disease.19

In this case, the high proportion of eosinophils in the cytologic smears of the peritoneal effusion raised the possibility of underlying eosinophilic inflammatory bowel disease. Eosinophils were part of the inflammatory infiltrate identified in the lamina propria on histologic examination of the intestinal biopsies; however, the main inflammatory cell type in the intestine were lymphocytes and plasma cells. The pleural fluid had a lower but still increased proportion of eosinophils. One could speculate that the fluid accumulation in the thoracic cavity has a component of lymph originating from the abdomen (i.e. the eosinophils in the pleural fluid are coming from the intestine and not from an intrathoracic organ) that is modified by the addition of lymph draining from other sources. Unfortunately, a high proportion of eosinophils in effusions is not specific as to the underlying cause of the effusion, being seen with neoplasia, trauma, pneumothorax, and fungal or parasitic infections.24-26 One reported case did have intestinal lymphangiectasia.24 In the dog of this report, trauma and pneumothorax were ruled out from the history and diagnostic testing, neoplasia was unlikely due to the dog’s young age and imaging findings, and testing for certain parasites was negative.

Authors: T Stokol, S Smith, K Simpson

References

- Mann CV, Shorter RG. Structure of the canine esophagus and its sphincters. J Surg Res. 1964 Apr 1;4(4):160–3.

- Chong VH. Clinical significance of heterotopic gastric mucosal patch of the proximal esophagus. World J Gastroenterol. 2013 Jan 21;19(3):331–8.

- Gianella P, Cagnasso F, Giordano A, Borrelli A, Bottero E, Bruno B, et al. Comparative Evaluation of Lipid Profile, C-Reactive Protein and Paraoxonase-1 Activity in Dogs with Inflammatory Protein-Losing Enteropathy and Healthy Dogs. Animals (Basel). 2024 Oct 29;14(21):3119.

- Salavati Schmitz S, Gow A, Bommer N, Morrison L, Mellanby R. Diagnostic features, treatment, and outcome of dogs with inflammatory protein‐losing enteropathy. J Vet Intern Med. 2019;33(5):2005–13.

- Lyngby JG, Sellon RK. Hypoadrenocorticism mimicking protein-losing enteropathy in 4 dogs. Can Vet J. 2016 Jul;57(7):757–60.

- Da Riz F, Higgs P, Ruiz G. Diseases associated with hypercobalaminemia in dogs in United Kingdom: A retrospective study of 47 dogs. Can Vet J. 2021 Jun;62(6):611–6.

- Kather S, Grützner N, Kook PH, Dengler F, Heilmann RM. Review of cobalamin status and disorders of cobalamin metabolism in dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2020 Jan;34(1):13-28.

- Yin Y, Li H, Feng J, Zheng K, Yoshida E, Wang L, et al. Prevalence and Clinical and Endoscopic Characteristics of Cervical Inlet Patch (Heterotopic Gastric Mucosa): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2022 Mar 1;56(3):e250–62.

- Rusu R, Ishaq S, Wong T, Dunn JM. Cervical inlet patch: new insights into diagnosis and endoscopic therapy. Frontline Gastroenterology. 2017 Nov 9;9(3):214.

- Ciocalteu A, Popa P, Ionescu M, Gheonea DI. Issues and controversies in esophageal inlet patch. World J Gastroenterol. 2019 Aug 14;25(30):4061–73.

- Romańczyk M, Budzyń K, Romańczyk T, Lesińska M, Koziej M, Hartleb M, et al. Heterotopic Gastric Mucosa in the Proximal Esophagus: Prospective Study and Systematic Review on Relationships with Endoscopic Findings and Clinical Data. Dysphagia. 2023 Apr;38(2):629–40.

- Patricia-Rae Meyer B, Nguyen J, Wilsey M, Karjoo S. Heterotopic Gastric Mucosa Causing Rectal Bleeding in a Young Child. JPGN Rep. 2022 May;3(2):e184.

- Iwata H, Arai C, Koike Y, Hirouchi Y, Kobayashi K, Nomura Y, et al. Heterotopic gastric mucosa of the small intestine in laboratory beagle dogs. Toxicol Pathol. 1990;18(3):373–9.

- Tobleman BN, Sinnott VB. Heterotopic gastric mucosa associated with abdominal abscess formation, hypotension, and acute abdominal pain in a puppy. J Vet Emerg Crit Care (San Antonio). 2014;24(6):745–50.

- Merca R, Richter B. Life-threatening gastrointestinal bleeding caused by jejunal heterotopic gastric mucosa in an adult dog: a rare case report. BMC Vet Res. 2022 Aug 16;18(1):315.

- Gillen P, Keeling P, Byrne PJ, West AB, Hennessy TP. Experimental columnar metaplasia in the canine oesophagus. Br J Surg. 1988 Feb;75(2):113–5.

- Panigrahi D, Johnson AN, Wosu NJ. Adenocarcinoma arising from gastric heterotopia in the jejunal mucosa of a beagle dog. Vet Pathol. 1994 Mar;31(2):278–80.

- Orosey M, Amin M, Cappell MS. A 14-Year Study of 398 Esophageal Adenocarcinomas Diagnosed Among 156,256 EGDs Performed at Two Large Hospitals: An Inlet Patch Is Proposed as a Significant Risk Factor for Proximal Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. Dig Dis Sci. 2018 Feb;63(2):452–65.

- Malatos JM, Kurpios NA, Duhamel GE. Small Intestinal Lymphatic Hypoplasia in Three Dogs with Clinical Signs of Protein-losing Enteropathy. J Comp Pathol. 2018 Apr;160:39–49.

- Jablonski SA. Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Management of Canine Intestinal Lymphangiectasia: A Comparative Review. Animals (Basel). 2022 Oct 15;12(20):2791.

- Ross JD, Reid KDG, Ambujakshan VP, Kinloch JD, Sircus W. Recurrent pleural effusion, protein-losing enteropathy, malabsorption, and mosaic warts associated with generalized lymphatic hypoplasia. Thorax. 1971 Jan;26(1):119–24.

- Werner LL, Turnwald GH, Willard MD. Immunologic and Plasma Protein Disorders. In Small Animal Clinical Diagnosis by Laboratory Methods (4th edition). Eds, Willard MD and Tvedten H. 2004; pp. 290–305.

- Stokol T , Tarrant JM, Scarlett JM. Overestimation of canine albumin concentration with the bromcresol green method in heparinized plasma samples. Vet Clin Pathol. 2001;30(4):170–6.

- Fossum TW, Wellman M, Relford RL, Slater MR. Eosinophilic pleural or peritoneal effusions in dogs and cats: 14 cases (1986-1992). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1993 Jun 1;202(11):1873–6.

- Piech TL, Jaffey JA, Hostnik ET, White ME. Bicavitary eosinophilic effusion in a dog with coccidioidomycosis. J Vet Intern Med. 2020 Jul;34(4):1582–6.

- Allison R, Williams P, Lansdowne J, Lappin M, Jensen T, Lindsay D. Fatal hepatic sarcocystosis in a puppy with eosinophilia and eosinophilic peritoneal effusion. Vet Clin Pathol. 2006 Sep;35:353–7.