Interpretation

Bone marrow aplasia from bracken fern toxicity.

Explanation

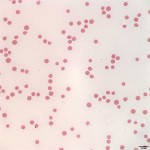

Pancytopenia is noted on the CBC (Question 1), i.e. anemia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia. The most common red blood cell morphologic changes associated with erythroid regeneration in cattle are polychromasia and basophilic stippling, neither of which is noted in the images from the blood smear (Figure 1), indicating that the anemia is non-regenerative (Question 1). The mildly decreased MCV and MCH are likely related to the young age of the steer, as cattle may be microcytic up to about 1 year of age. The lack of leukocytes and platelets in Figure 1 support the automated CBC findings of leukopenia and marked thrombocytopenia.

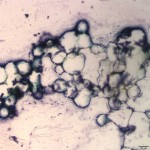

Normal bone marrow should be composed of roughly equal parts of hematopoietic cells and fat. Figure 2 shows that the bone marrow from this steer is almost all fat, with only rare hematopoietic cells. This is interpreted as bone marrow aplasia, indicating that the cytopenias on the CBC are due to decreased production of hematopoietic cells by the bone marrow (Question 2). The petechiation noted clinically is likely due to the severe thrombocytopenia secondary to decreased production of platelets by the bone marrow (Question 2).

Discussion

Petechiation is usually associated with disorders of primary hemostasis, i.e. involving platelets, von Willebrand factor, and the vascular wall. In cattle, petechiation would be most likely be caused by thrombocytopenia. von Willebrand disease has only been suggested in one case report from cattle,1 so would be unlikely. Petechiation can occur due to vasculitis in cattle (e.g. due to malignant catarrhal fever), but would be expected to also be associated with other clinical signs such as edema. A disorder of secondary hemostasis, such a deficiency of active coagulation factors due to anticoagulant rodenticide toxicity, could cause a bleeding disorder, but would be expected to cause larger bleeds rather than petechiation. The platelet count in this steer was severely decreased, confirming that the petechiation was due to thrombocytopenia. Additionally, the CBC indicates that there are decreases in multiple hematopoietic lineages, i.e. pancytopenia (anemia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia). The most common cause of pancytopenia is bone marrow pathology, such as bone marrow aplasia or myelophthisis. Bone marrow sampling is often helpful is distinguishing causes of pancytopenia. Myelophthisis is the replacement of normal hematopoietic cells in marrow with an abnormal cell type, such as leukemia or infiltrating lymphoma. These abnormal cell types can lead to peripheral blood cytopenias not only because they crowd out normal hematopoietic precursors, but also because they can alter the bone marrow microenvironment making it difficult for normal precursors to proliferate. In these cases, sampling of bone marrow often reveals an abundance of the neoplastic cells with very few normal hematopoietic precursors.

Bone marrow aplasia occurs due to damage to early stage hematopoietic stem cells, creating a bone marrow that is mostly devoid of hematopoietic precursors and predominated by fat and stromal cells. There are multiple causes of bone marrow aplasia. In cattle, it is commonly caused by bracken fern toxicity (Question 3). Other reported causes are rare in cattle and include idiosyncratic drug reactions, congenital abnormalities (if present in very young calves), and consumption of soybean meal extracted with trichloroethylene.2 The post-mortem bone marrow cytologic findings from this steer indicated that the bone marrow was composed mostly of fat, compatible with bone marrow aplasia. The referring veterinarian indicated that there was bracken fern in the area where the cattle were kept.

Bracken fern has a very wide geographic distribution around the world, and grows in a variety of conditions, including in woodlands and open pastures. The plant emerges in early spring as a small curved frond (“fiddlehead”), and will mature and remain green until killed by frost. The mature frond is divided into 3 leaflets which are broad and triangular. A distinguishing feature is that the small sub-leaflets are lobed at the base, but not at the tip.3 All portions of the bracken fern are toxic to cattle, horses, and sheep, although sheep may be more resistant. Ingestion can be associated with a variety of syndromes, depending on the species, the dose, and the duration of exposure.

- Acute bracken fern toxicosis in cattle4,5: There are several toxic compounds in bracken fern that are radiomimetic and carcinogenic in cattle, most notably ptaquiloside. The radiomimetic properties injury bone marrow stem cells of all lineages, leading to bone marrow aplasia and peripheral blood pancytopenia when high levels are consumed over a short period of time. The first clinical finding is usually a hemorrhagic syndrome due to severe thrombocytopenia. Epistaxis, hematuria, and petechial hemorrhages on mucosal surfaces and sclera are common. Affected animals are also often predisposed to sepsis due to neutropenia. Mortality in these cattle is generally quite high, often >90%.

- Chronic bracken fern toxicosis in cattle4-6: When consumed at lower doses for longer periods of time, bracken fern has a cumulative carcinogenic effect. Ptaquiloside is excreted in the urine and can cause bladder irritation and development of bladder neoplasia. The toxic compounds may cause recrudescence of latent bladder infection with bovine papillomavirus-2 (BPV-2) and it has been proposed that the virus may interact with the mutagenic compounds in the bladder to promote neoplasia. Epithelial, mesenchymal, or mixed tumor types have been reported. Ptaquiloside is also excreted in the milk and consumption of milk from these cattle has been experimentally associated with gastrointestinal tumors in rats. There is also epidemiologic evidence to support that ingestion by humans of milk from affected cattle or of bracken fern fiddleheads is associated with increased risk of gastrointestinal neoplasia.

- Bracken staggers in horses3-5: A thiaminase is the main toxic compound for horses ingesting bracken fern. This leads to vitamin B1 deficiency, which is usually responsive to treatment with thiamine if detected early enough. Clinical signs of bracken fern toxicosis in horses are predominantly neurologic signs, incoordination, weakness, muscle tremors, and, in severe cases, tachycardia and arrhythmias. Anorexia and weight loss are also common.

Summary

In cattle, the radiomimetic effects of bracken fern can damage hematopoietic stem cells when acutely ingested in large amounts or can be carcinogenic if consumed chronically in smaller doses. Hematuria can be detected in cattle with bracken fern toxicity due to multiple mechanisms, including thrombocytopenia, bladder irritation, or bleeding bladder tumors, and as such the condition is also referred to as bovine enzootic hematuria.

References

- Sullivan P, Grubbs ST, Olchowy TW, et al. Bleeding diathesis associated with variant von Willebrand factor in a Simmental calf. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1994;205:1763-6.

- Harvey JW. Disorders of bone marrow, Chapter 9. In: Veterinary hematology, a diagnostic guide and color atlas. St Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier, 2012;260-327.

- Bebbington A, Wright B. Bracken-fern poisoning in horses. Ministry of agriculture, food, and rural affairs, Ontario. Order No. 09-049, AGDEX 663/460. October 2009.

- Van Metre DC, Divers TJ. Enzootic Hematuria. In: Large animal internal medicine, 3rd ed. Smith BP (ed). St Louis, MO: Mosby, 2002;862-863.

- Stegelmeier BL. Overview of bracken fern poisoning. In: The Merck Veterinary Manual for Veterinary Professionals. Revised Feb 2014.

- Perez-Alenza MD, Blanco J, Sardon D, et al. Clinicopathologic findings in cattle exposed to chronic bracken fern toxicity. N Zeal Vet J 2006; 54:185-192.