Interpretation

Septic suppurative inflammation (exudative effusion) due to a gastric rupture

Explanation

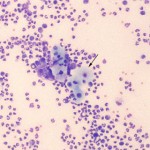

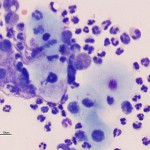

The direct smear of the peritoneal fluid was of high cellularity and consisted of >95% degenerate neutrophils, with low numbers of macrophages and rare lymphocytes. A mixed population of bacteria was observed phagocytized within the neutrophils (not shown in the images). Low numbers of nucleated keratinized squamous epithelial cells were observed individually and in small clusters in the fluid, sometimes associated with neutrophils. These were interpreted to originate from the squamous portion of the gastric mucosa and their presence in the fluid was compatible with an acute gastric rupture with secondary inflammation and bacterial sepsis. The fluid was grossly turbid and orange (see image to the right). The supernatant was still turbid after centrifugation, compatible with lipid (in this case, this was attributed to ingestion of milk, with hemorrhage contributing to the orange color). The table below provides the remaining cytologic results of the fluid.

| Table 1: Peritoneal fluid results | |||

| Test | Result | Units | Ref Interval |

| Nucleated cell count | 845 | x 103/μL | <1.51 |

| Red blood cell count | 70 | x 103/μL | – |

| Protein by refractometer | 6.4 | g/dL | <2.51 |

Further information and follow-up

An abdominal ultrasound performed just prior to abdominocentesis revealed a large amount of gas in the abdomen. A standing right lateral abdominal radiograph revealed severe pneumoperitoneum with ventral displacement of the intestines. There was also an obvious fluid line (this fluid was aspirated) and complete loss of serosal detail (Figure 4). These findings supported a gastric rupture.

The foal was taken to surgery, which revealed a large amount (2 liters) of fibrinous fluid containing a small amount of feed material. A 1.5 cm full thickness tear was evident in the gastric wall between the greater and lesser curvatures. The tear was repaired and the abdomen was flushed with saline then instilled with carboxymethylcellose (to prevent adhesions). The foal was treated with fluids and antibiotics after surgery and was observed to stand and nurse within 4 hours of surgery. The inflammatory leukogram resolved the day after surgery although the hyperfibrinogenemia persisted. A repeat abdominocentesis also indicated resolving peritonitis (nucleated cell count of 28 x 103/uL, consisting of mixed neutrophils and macrophages with no evidence of bacteria, and a total protein by refractometer of < 2.5 g/L). The foal was discharged to the owner 12 days after hospitalization and was alive and well 2 months later.

Discussion

Rupture or perforation of the gastric mucosa is an uncommon cause of abdominal distension in adult horses and foals. Ruptures typically occur secondary to overdistension of the stomach, either due to a primary gastric disorder (grain overload, ulcerative gastritis, and gastric impaction) or secondary to gastrointestinal problems distal to the stomach (small intestinal strangulation, intussusception, and volvulus, and large colon displacement and impaction).2 Greater than 90% of ruptures occur along the greater curvature of the stomach. Perforations are more focal lesions that are usually secondary to underlying gastric ulcers. In one study, all foals under 3 months of age had a pre-existing ulcerative gastritis, which weakened the gastric wall leading to a full thickness rupture.3

There is a high prevalence of gastric ulceration in foals less than three months of age (50%), with an even higher incidence in neonatal intensive care units.4 Lesions can be located in the glandular mucosa, but the most common location for ulcers in the nonglandular squamous mucosa along the margo plicatus.4 The cause of gastroduodenal ulceration in foals is not entirely understood but associated risk factors are diarrhea, decreased prostaglandin E2 synthesis secondary to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (prostaglandin promotes mucosal blood flow, mucus production and bicarbonate secretion and inhibits hydrochloric acid secretion, thus having an overall protective effect on the stomach), decreased secretion of salivary bicarbonate (which neutralizes the eroding effects of hydrochloric acid), an under-developed gastric mucosa (the nonglandular squamous mucosa undergoes vigorous epithelial hyperplasia and keratinization from late gestation through the first week of life) and stress. Ulcers are difficult to diagnose because they are frequently asymptomatic or result in vague clinical signs (bruxism, ptyalism, post-prandial colic, recumbency, poor appetite). Perforations can result in severe colic with fulminant peritonitis or sudden death.5

In this foal, the rupture occurred along the margo plicatus and was presumed secondary to prior gastric ulceration, although this was not confirmed. Gastric rupture or perforation is almost universally fatal in horses, with only two reports of successful surgical correction.6.7 The survival of the foal in this case was attributed to the fortuitous hospitalization and close monitoring of the foal when the acute rupture rupture occurred, the rapid diagnosis based on the supportive imaging and cytologic findings, and the aggressive, prompt surgical intervention.

References

- Grindem, CB, Fairley, CA, et al. Peritoneal fluid values from healthy foals. Equine Vet J 22 (5): 359-361, 1990.

- Kiper LK, Traub-Dargatz J et al. Gastric rupture in horses: 50 cases (1979-1987). J Am Vet Med Assoc 196 (2): 333-336, 1990.

- Todhunter RJ, Erb HN, Roth L. Gastric rupture in horses: a review of 54 cases. Equine Vet J 18 (4): 288-293, 1986.

- Murray, MJ. Gastroduodenal ulceration. In Bayly, WM: Equine Internal Medicine. Saunders (W.B.) Co Ltd. 1997, p.615-623.

- Knottenbelt, DC. Equine Neonatology Medicine and Surgery. Saunders (W.B.) Co Ltd. 2004, p.252-255.

- Hogan PM, Bramlage LR. Repair of a full-thickness gastric rupture in a horse. J Am Vet Med Assoc 207 (3): 338-340, 1995.

- Probst CW, Schneider RK, et al. Surgical Repair of a perforated ulcer in a foal. Vet Surg 12 (2): 93-95, 1983.