Interpretation

Lymphoma

Explanation

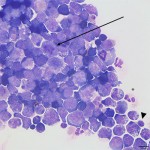

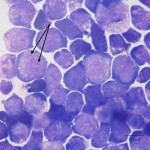

Normal canine CSF collected from the lumbosacral space is clear and colorless, with a low total protein (<45 mg/dL) and low nucleated cell count (<5 cells/uL). Most cells in normal CSF fluid are mononuclear cells and are a mixture of macrophages and small lymphocytes. Low numbers of non-degenerate neutrophils and rare eosinophils may also be present.1 The total protein concentration and the nucleated cell count are both markedly increased in this dog’s CSF. The cytospin smear is of very high cellularity and is dominated by a monomorphic population of intermediate to large lymphoblasts, along with fewer small lymphocytes, non-degenerate neutrophils, and macrophages. A few erythrocytes are noted in the background (Figure 3). The lymphoblasts have a high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio, round nuclei, fine chromatin, 1-2 variably distinct nucleoli, and a small amount of deep blue cytoplasm that occasionally contains a few small clear vacuoles (Figure 4). Numerous mitotic figures and moderate numbers of apoptotic neoplastic cells are seen. The morphologic features of these cells are compatible with lymphoma, and their presence within the CSF indicates involvement of the central nervous system.

|

|

Discussion

Lymphoma is a common cancer in dogs that accounts for 7-24% of all canine cancers and up to 83% of hematopoietic neoplasms.2 Breeds that appear to be at increased risk for the development of lymphoma include boxers, bull dogs, bull mastiffs, basset hounds, and Golden Retrievers.2,3 Most dogs present with the multicentric form of lymphoma, with involvement of multiple peripheral lymph nodes, internal organs (liver, spleen), and/or bone marrow. Lymphoma within the central nervous system (CNS) is usually part of a multicentric process, and primary CNS lymphoma is considered rare. Both primary and multicentric forms of lymphoma may have solitary or multifocal CNS involvement and the neoplasm can be of B or T cell origin. These findings are in contrast to the presentation in the cat, where CNS lymphoma is often primary, and multiple organ involvement is less common.3 In a study of dogs with primary intracranial tumors, 58% of the CSF samples had an increased total nucleated cell count, while 30% were characterized by increased total protein alone (albuminocytologic or protein-cytologic dissociation). The most common cytologic abnormality in the CSF was a mixed cell pleocytosis. This case series included 6 dogs with lymphoma – their CSF findings ranged from protein-cytologic dissociation (n=3) to a mixed cell or lymphocytic pleocytosis (n=2; CSF was not collected in one dog).4 Similar to this case, in an earlier study of CNS lymphoma in 8 dogs, high nucleated cell counts with neoplastic lymphoblasts were seen in all 7 evaluated CSF samples.5 Importantly, the absence of neoplastic cells in CSF cannot be used to rule out lymphoma, as normal or equivocal CSF findings have been reported in dogs with histopathologically confirmed lymphoma.4,6 Indeed, in the study by Snyder et al4, lymphoblasts were only definitively identified in the CSF of 1 of the 6 dogs with lymphoma. Since CSF analysis is a relatively non-invasive, safe and inexpensive procedure, collection of CSF for assessment for the presence of neoplastic cells would be worthwhile in dogs with evidence of infiltrative disease processes. A diagnosis of lymphoma would be favored by the presence of a dominant population of intermediate to large round mononuclear cells, with high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratios, fine chromatin, and variably distinct nucleoli. The presence of mitotic figures, particularly if abnormal, would be further support of a neoplastic process. Note, that large lymphocytes can be seen in various inflammatory CNS disorders, such as granulomatous meningoencephalitis. In these conditions, they usually comprise a low proportion of the lymphoid cells and have cytologic features more consistent with reactive cells (clumped chromatin, deep blue smooth cytoplasm, no nucleoli).

Follow up

The dog’s neurologic signs progressed rapidly over the next 12 hours; he became paraplegic with no deep pain response or withdrawal reflexes in the hind limbs and developed Schiff-Sherrington syndrome. Given the rapid decline in neurologic status, the dog was euthanized without additional diagnostic tests. It is unknown whether the CNS lymphoma was primary or part of a multicentric disease process.

References

- DeLorenzi D and Mandara MT. The Central Nervous System. In: Raskin RE, Meyer DJ, eds. Canine and feline cytology. 2nd ed. St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier, 2010;325-365.

- Rowell JL, et al. Dog Models of Naturally Occurring Cancer. Trends Mol Med 2011;17(7):380–384.

- Vail DM and Young KM. Hematopoietic Tumors. In: Withrow SJ, Vail DM, eds. Small Animal Clinical Oncology. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier, 2007;699-733.

- Snyder JM, et al. Canine intracranial primary neoplasia: 173 cases (1986-2003). J Vet Intern Med 2006;20:669-675.

- Couto CG, et al. Central nervous system lymphosarcoma in the dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1984; 184:809-813

- Long SN, et al. Primary T-cell lymphoma of the central nervous system in the dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2001;218:719-722.