Interpretation

Eosinophilic inflammation with mildly dysplastic corneal epithelial cells. These findings are consistent with eosinophilic keratitis.

Explanation

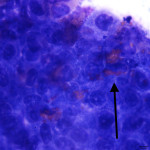

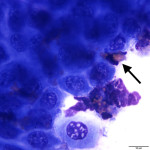

The corneal scrape was highly cellular and contained predominantly large sheets of corneal epithelial cells with moderate numbers of eosinophils percolating through the sheets (answer to question 1). The epithelial cells ranged in shape from cuboidal to columnar, and displayed mild anisocytosis and anisokaryosis (answer to question 2). Focal pockets of degenerating epithelial cells were found (suspected to be areas of necrosis). A small amount of basophilic extracellular material was also seen, and presumed to be the previously administered ointment. There was no evidence of any infectious agent. These findings are consistent with eosinophilic keratitis, but careful evaluation of the sample for any evidence of co-infection with the more common cause of corneal ulceration (bacterial and fungal infections) in horses is prudent (answer to question 3).

Discussion

Eosinophilic keratitis (EK) in horses is a seasonal disease, with the highest incidence in the summer months, peaking in July. The diagnosis of the condition is based on clinical signs, which can overlap with other cause of keratitis in the horse, and cytologic findings. Scrapes from these lesions yield epithelial cells and numerous eosinophils. Inflammatory cells may also include low numbers of mast cells, lymphocytes, and plasma cells.1-6 Occasionally, the cytological findings vary and coalesced eosinophilic debris, rather than intact cells, is a clue to the underlying etiology (personal experience). There are no recognized breed associations, but identification of any such relationship is hampered by the relatively low number of published studies. The disease is commonly bilateral in presentation.1 The underlying etiology is not definitively know, but a delayed hypersensitivity response to allergens or parasites has been suggested.1,2,6 The inflammation is currently thought to be localized, as there have been no reports documenting either a peripheral eosiniophilia or increase in plasma IgE levels in affected horses. The condition tends to respond to an extended course of systemic immunosuppressive therapy, while refractoriness to topical treatment alone has been recognized.1,2 Additional therapy to address pain, and to eliminate or prevent any-coinfection, is often included in the treatment regimen.1 Treatment with an H1 antagonist (cetirizine), has been reported to reduce the incidence of disease recurrence, but did not appear to shorten the duration of the initial disease.1 The addition of a superficial keratectomy has been reported to expedite resolution of the disease.3,4,5,6 Major basic protein, one of the main constituents in eosinophil granules (and the reason they have those lovely pink granules), has been proven toxin to epithelial cells in culture and implicating in slowing wound healing.7 Co-existing bacterial and/or fungal infections are frequently identified cytologically in horses with EK, with a low number of horses culturing positive without cytological evidence of infection. In a series of cases reported out of the University of Pennsylvania’s New Bolton Center, pre-treatment with topical steroids did not statistically increase the rate of co-infection.1 Average time to disease resolution reported in the literature averages 3.7 months.1 While cytology can be extremely helpful in ascertaining the initial diagnosis, the cytological evidence of an eosinophilic infiltrate has been reported to clear prior to resolution of clinical signs. Thus, cytology is not considered an appropriate monitoring tool.1 Thorough evaluation for the more common infectious causes of equine keratitis; Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Pseudomonas, Aspergillus, and Fusarium, is absolutely essential.7,8,9 These pathogens should also be excluded as potential secondary invaders of an already damaged cornea.

References

1. Brooks DE. Equine ophthalmology. In: Gelatt KN, editor. Veterinary ophthalmology. 3rd edition. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999. p. 1053–116.

2. Lassaline-Utter M, Miller C, Wotman KL. Eosinophilic keratitis in 46 eyes of 27 horses in the Mid-Atlantic United States (2008–2012) Veterinary Ophthalmology 2014:311–320.

3. Ramsey DT, Whiteley HE, Gerding PA Jr et al. Eosinophilic keratoconjunctivitis in a horse. Journal of the American Veterinary Association 1994:1308–1311.

4. Yamagata M, Wilkie DA, Gilger BC. Eosinophilic keratoconjunctivitis in seven horses. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 1996:1283–1286.

5. Sandberg CA, Herring IP, Schorling JJ et al. Ulcerative eosinophilic keratoconjunctivitis in three horses: clinical course and characterization by electron microscopy. Abstracts: 39th Annual Meeting of the American College of Veterinary Ophthalmologists. Veterinary Ophthalmology 2008; 11: 413–429

6. Kafarnik C. Equine eosinophilic keratitis. Companion Animal 2010:15: 4–6

7. Trocme SD, Gleich GJ, Kephart GM et al. Eosinophil granule major basic protein inhibition of corneal epithelial wound healing. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 1994:3051–3056.

7. Davidson MG. Equine ophthalmology. In: Gelatt KN, editor. Veterinary ophthalmology. 2nd edition. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1991:576–610.

8. Moore CP, Fales WH, Whittington P, Bauer L. Bacterial and fungal isolates from Equidae with ulcerative keratitis. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1983:600–603.

9. McLaughlin SA, Brightman AH, Helper LC, Manning JP, Tomes JE. Pathogenic bacteria and fungi associated with extraocular disease in the horse. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1983: 241–242.