Intrepretation

Mixed inflammation with phagocytized foreign material

Explanation

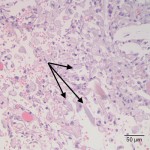

The smears contain moderate numbers of mixed inflammatory cells, consisting mostly of non-degenerate to mildly degenerate neutrophils with fewer macrophages (Figure 1). The macrophages frequently contain a moderate to abundant amount of mid-blue variably-shaped and occasionally linear phagocytized material (Figure 1, inset). Similar material is rarely found in the background (not pictured). Although the precise identity of this material cannot be definitively determined cytologically, it is consistent with foreign material and the linear appearance is reminiscent of surgical sponge fibers. Other foreign material or degrading fungal hyphae are possible differential diagnoses.

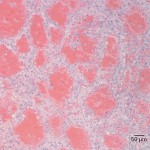

Scattered throughout the smears are also low numbers of large spindle-shaped to oval cells that are arranged individually and in aggregates (Figure 2). These cells display moderate anisocytosis and anisokaryosis, and have a moderate nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio, somewhat indistinct cellular boundaries, deep blue cytoplasm that occasionally contains a few small pink granules, oval nuclei, stippled chromatin, and 1-5 variably distinct small nucleoli. These cells represent a mesenchymal cell population that displays moderate features of atypia. In the context of the mixed inflammatory response, the morphology and distribution of these cells could be compatible with reactive fibroblasts. However, sarcoma cannot be ruled out and histopathology is required to distinguish between the two possibilities.

Other findings not depicted in the photomicrographs included low numbers of erythrophagocytic macrophages (indicating hemorrhage) and a small amount of necrotic debris.

Further information and follow up

An exploratory laparotomy was performed and the mass was fully resected and submitted for histopathologic evaluation. Grossly, the mass was multi-lobulated and cavitated, with an irregular outer surface. A small amount of synthetic fibrous material (presumptive surgical sponge) was found embedded within the tissue. Histopathologically, the mass was quite heterogenous, consisting of multifocal areas of extensive granulomatous inflammation, fibrosis, and necrosis, along with a neoplastic population. The granulomatous inflammation was characterized by numerous foamy macrophages surrounding linear fragments of material, compatible with synthetic surgical sponge fibers (Figure 3). Arising from the granulation tissue was a population of pleomorphic spindle-shaped cells arranged in streams that frequently formed large vascular channels (Figure 4). The histopathologic diagnosis was a sarcoma arising from a locally extensive area of granulomatous foreign body peritonitis (gossypiboma). Given the formation of vascular channels within the neoplastic portions of the mass, the top differential for the sarcoma was hemangiosarcoma, although extraskeletal osteosarcoma could not be completely ruled out. The diagnosis could be confirmed with immunohistochemistry for the endothelial cell marker, von Willebrand factor, although this was not performed in this case.

|

|

|

Discussion

The term gossypiboma, or textiloma, refers to the inflammatory reaction caused by a retained surgical sponge. Gossypibomas are an uncommon surgical complication in human medicine, and are rarely reported in veterinary medicine.1,2 Retained surgical sponges may result in acute abscess formation and/or exudation that are usually detected soon after surgery. Alternatively, a retained surgical sponge may incite a more chronic granulomatous inflammatory response that results in a mass lesion.3 Some authors use the term “gossypiboma” specifically to refer to this type of granulomatous response. The time between surgery and formation of a mass is variable, and the lesion may take days to weeks to even years to develop.4

Occasionally, cells within a gossypiboma may undergo neoplastic transformation, as has occurred in this case. Of the few reports in dogs, most of the tumors have been extraskeletal osteosarcomas, although a fibrosarcoma has also been reported.4,5 There is one report of a fibrosarcoma secondary to a retained surgical sponge in a cat.6 In human medicine, the most common tumor associated with gossypibomas is angiosarcoma, an otherwise uncommon tumor type in people.5 Interestingly, the top differential diagnosis for the tumor type in this case was a hemangiosarcoma, a relatively common tumor in dogs that is similar to human angiosarcoma, but is not usually associated with a foreign body reaction.

In the human medical community, gossypibomas have been identified as an unacceptable but preventable iatrogenic surgical complication. To minimize patient discomfort, morbidity, and mortality as well as the costly legal proceedings due to retained surgical sponges, human hospitals have enacted strict rules to prevent the error of a retained surgical sponge or other material.7 Measures include meticulous and repeated counting of surgical sponges before the start of surgery, before initial closure, and again before skin closure.7 Radiographs or other imaging techniques may be used to evaluate for surgical sponges post-operatively. Surgical sponges impregnated with radio-opaque material can enhance radiographic detection.2 Despite these measures, retained surgical sponges still occur, and newer technologies include the use of radiofrequency identification tags on sponges that are detected by waving a wand over the patient and operative field during surgery.1,7

References

- McIntyre, L.K. et al. Gossypiboma: tales of lost sponges and lessons learned. Arch Surg. 2010;145:770-775.

- Merlo, M. et al. Radiographic and ultrasonographic features of retained surgical sponge in eight dogs. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 2000;41:279-283.

- Frank, J.D. and Stanley, B.J. Enterocutaneous fistula in a dog secondary to an intraperitoneal gauze foreign body. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2009;45:84-88.

- Miller, M.A. et al. Extraskeletal osteosarcoma associated with a retained surgical sponge in a dog. J Vet Diagn Invest 2006;18:224-228.

- Rayner, E.L. Abdominal fibrosarcoma associated with a retained surgical swab in a dog. J Comp Path 2010;143:81-85.

- Haddad, J. L. Fibrosarcoma arising at the site of a retained surgical sponge in a cat. Vet Clin Path 2010;39:241-246.

- Zahiri, H.R. et al. Prevention of 3 “never events” in the operating room: fires, gossypiboma, and wrong-site surgery. Surg Innov 2011;18:55-60.