Interpretation

Idiopathic feline pure red cell aplasia.

Explanation

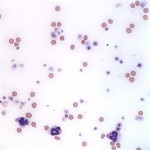

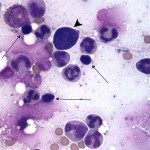

Despite the high percentage reticulocytes measured by the automated analyzer, the low absolute reticulocyte count indicates that the anemia is non-regenerative. In fact, given the complete lack of polychromatophils on the blood smear (Figure 1), the identification of any reticulocytes by the analyzer is questionable and these results were interpreted to be inaccurate. It is always advisable to check any automated hematology results by blood smear examination to detect these issues. The anemia can be classified as a severe normocytic normochromic non-regenerative anemia (Question 1). Agglutination was noted on the smear suggesting an immune-mediated mechanism for the anemia. The bone marrow smear revealed a mildly increased cellularity. Myeloid precursors and megakaryocytes (thick arrows) are abundant and maturation is complete and balanced but only rare erythroid precursors are present (rubriblasts – arrowhead) and no polychromasia is observed on the bone marrow smear (Figure 2b, taken on 1000x magnification). The myeloid to erythroid ratio is markedly elevated (Question 2). There is also a lymphocytosis (thin arrows) with focal aggregates of plasma cells. Overall, the finding of severe erythroid hypoplasia in bone marrow with sparing of both the myeloid and megakaryocytic lineages is compatible with a diagnosis of pure red cell aplasia (PRCA).1 The elevated ALT and AST values indicate hepatocellular injury likely resulting from hypoxia as a result of the severe anemia. The hyperferremia is attributed to the lack of erythropoiesis resulting in decreased iron utilization (Question 3).

Discussion

Non-regenerative anemia results from the inability of bone marrow to respond appropriately to a peripheral deficiency in erythrocytes.2 There are multiple etiologies for non-regenerative anemia in cats, including primary diseases of bone marrow and systemic diseases that have secondary effects on the bone marrow via a variety of mechanisms such as decreased erythropoietin secretion, iron sequestration and reduced red cell survival.3 Anemia of inflammatory disease is the most common cause of non-regenerative anemia in veterinary medicine, but as seen in other secondary systemic conditions, the severity of the anemia is usually only mild to moderate.2 Primary bone marrow diseases are more likely to result in moderate to severe anemia, as observed in this patient. In a retrospective study of anemic cats, primary bone marrow diseases, such as myeloproliferative and myelodysplastic disorders, lymphoproliferative neoplasia and PRCA, were the most common causes identified for severe anemia.4 However, of all the disorders listed, PRCA is the only one that targets primarily erythroid precursors with no effect on myeloid or platelet precursors and as such a diagnosis of PRCA was made in this patient. 1,5

PRCA is characterized by a severe normocytic, normochromic anemia with reticulocytopenia and with no decrease in leukocyte or platelet counts. It is an acquired syndrome that can arise secondary to a systemic infection or as a primary idiopathic disorder.6 FeLV subgroup C has been implicated in this syndrome, and PRCA may occur secondary to the cytopathic effects of the virus, however, FeLV-C has rarely been reported in naturally infected cats and most cats with PRCA are FeLV negative.1,6 Primary idiopathic PRCA is a diagnosis of exclusion, and is thought to be an immune mediated disease that affects young cats. The age of cats with primary PRCA ranges from 6 months to 9 years with a median age of 1.4 years; there is no known breed or gender predilection.6 Clinical signs at presentation typically include lethargy and anorexia of 2-16 days in duration.1 Abnormal physical exam findings include pale mucous membranes, systolic murmurs ranging from grade II-III/VI, gallop rhythms, and tachypnea. CBC abnormalities include severe normocytic, normochromic to hypochromic non-regenerative anemia with a normal total protein and biochemistry changes are generally mild and may include high aminotransferase activities, hyperferremia, hypokalemia, and hyperglycemia.1,6 Cats with primary PRCA may have a positive direct or indirect Coomb’s test, and they test negative for infectious diseases like FeLV/FIV and Mycoplasma haemofelis.6 Bone marrow aspirate is needed for confirmation of erythroid hypoplasia to aplasia with myeloid and megakaryocytes lineages within the normal limits; a high proportion of small lymphocytes is also commonly found in bone marrow of affected cats. 1,6

Aggressive treatment with packed red cell blood transfusions and immunosuppresive drugs are often necessary to achieve remission.1 Given the severity of the anemia at presentation, cats require red blood cell transfusions, with most cats requiring multiple blood transfusions during the hospital stay.6 Treatment with immunosuppressive medications usually results in remission of anemia within 3-5 weeks with most cats requiring long-term therapy.1 In a recent retrospective study, cats with PRCA treated with a combination of glucocorticoid and cyclosporine and achieved clinical remission in a median of 31 days and maintained in remission for a median 406 days. In the same study, relapse was common, particularly after drug discontinuation and most cats must be maintained on long-term low dose therapy.6 These findings were similar to those reported by Stokol et al who described rapid response to combination immunosuppressive drugs. Cats in this study often did not respond to prednisolone alone and relapse was common when the dosage of immunosuppressive drugs was decreased or discontinued.1

Further information and follow up

The patient was given one unit of packed red blood cells, which improved the PCV from 5% to 20%. Doxycycline was added to the initial therapy to address any possible Mycoplasma haemophilis infection and was discontinued after interpretation of the bone marrow aspirate. The patient was treated with a combination of prednisolone and cyclosporine. Two additional packed red cell blood transfusions were necessary during the first 10 days of treatment. However, the patient was able to consistently maintain her hematocrit above 25% by day 20 and clinical signs of lethargy and poor appetite had resolved. At last follow-up, one year since her diagnosis, her PCV has normalized at 33% and she continues to receive prednisolone and cyclosporine to prevent relapse.

Summary

This case illustrates some of the key features of PRCA in cats, including the young age of cats at presentation, the severity of their anemia and the need for aggressive immunosuppressive and transfusion therapies to manage these patients. Korman et al found that anemia severity in cats was not associated with survival at discharge. 4 This case illustrates this finding and suggests that anemia severity should not be used to decide whether or not to treat an anemic cat.

References

1. Stokol T, Blue JT. Pure red cell aplasia in cats: 9 cases. 1999. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 214:75-79.

2. Tasker, S. Diagnostic Approach to Anaemia in Cats.” In Practice. 34.7 (2012): 370-381.

3. Feldman BF. Non-regenerative anemia. In: Ettinger SJ, Feldman EC, eds. Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine, Diseases of the Dog and Cat. 2005. St. Louis: Elsevier Saunders:1908-1917.

4. Korman, RM, N Hetzel, TG Knowles, AM Harvey, and S Tasker. A Retrospective Study of 180 Anaemic Cats: Features, Aetiologies and Survival Data.” 2013. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. 15.2: 81-90.

5. Weiss, DJ. Bone Marrow Pathology in Dogs and Cats with Non-Regenerative Immune-Mediated Haemolytic Anaemia and Pure Red Cell Aplasia. 2008. Journal of Comparative Pathology. 138.1:46-53.

6. Viviano KR, Webb JL. Clinical use of cyclosporine as an adjunctive therapy in the management of feline idiopathic pure red cell aplasia. 2011. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. 13.12: 885-95.

Authored by: E. Sanmarti and H. Priest