Interpretation: Giardiasis

Explanation:

The fecal smear consists predominantly of a polymorphic bacterial population (Figure 1, thin arrow), which is consistent with normal gut flora (Question 1). There are several round, cyst-like structures of various sizes, the largest around 8 microns, containing a small amount of pink, smooth material (Figure 1, thick arrow). There is also amorphous light purple material in the background, likely indicating ingesta (Question 1). Differential diagnoses for the larger structures include Giardia spp and pseudoparasites such as pollen, fungal spores or bubbles (Question 2). Additional diagnostic tests that could be performed include a zinc sulfate fecal flotation, an ELISA test for Giardia, immunofluorescent assay (IFA), and PCR test (Question 3).

Additional testing and follow up

Additional testing consisted of a zinc sulfate fecal flotation.

| . |

|

|

. |

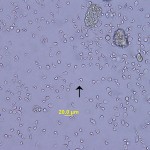

Upon examination, numerous ellipsoidal Giardia cysts were evident with some fecal debris (Figures 2 and 3). Giardia cysts contain two formed trophozoites, axonemes, ventral disk fragments, and up to four nuclei within the cyst wall. In this case, details of the internal contents of the cysts were not evident due to an osmotic artifact. This artifact pushes the cytoplasm up against the cyst wall, and gives the cyst a distinct crescent-shaped or diamond ring appearance characteristic of Giardia cysts (Figures 2 and 3).1

Discussion

Giardia spp are a protozoan flagellates that can cause infection in the intestinal tracts of a host of wild and domestic animal species, including human,s worldwide. There are a number of existing Giardia species with different host-specific adaptations; G. agilis in amphibians, G. ardeae and G. psittaci in birds, G. muris in rodents and G. microti in muskrats and voles, and G. varani in reptiles.2 Dogs are frequently infected with their host-adapted species, Giardia canis. However, Giardia duodenalis (also known as G. intestinalis or previously as G. lamblia) can have a wide range of host species including dogs, cats, and humans. There are 7 assemblages of G. duodenalis (assemblages A–G). Humans are mainly infected with assemblages A and B, dogs with C and D, and cats with F.3 Despite cross-species transmission, the risk of acquiring Giardia infections from pets is low in immunocompetent individuals.4 Recent epidemiological studies in the US demonstrated a decline in canine infections between 2003 and 2009, while human infections during the same time period were stable and displayed a seasonal trend.5 This speaks against a high rate of canine to human transmission in the US, but may not hold true in other regions of the globe. Groups that are at an increased risk for infection with Giardia, include children, people in communities where animals are kept close to or within the home, and parts of the world where concurrent infections are prevalent.4 Steps that can be taken to prevent the zoonotic transmission of giardiasis from household pets include frequent hand washing, cleaning and disinfecting areas frequented by pets, and other similar hygiene measures.4,6

The prevalence rates of giardiasis in dogs and cats range from 5-15%.7 Young animals are more likely to test positive for Giardia infection and prevalence rates ranging from 36-50% have been reported in puppies.4 According to a national survey of Giardia infection in pet dogs in the United States, the prevalence of giardiasis in puppies less than 6 months of age was 13.1%, while the prevalence in adult dogs greater than 3 years of age was <1%.7 Animals from shelters often have a higher prevalence of giardiasis than client-owned animals.7 In this case, the patient was both a young animal and was recently adopted from a shelter, making infection with Giardia highly probable.

The life cycle of Giardia consist of 2 stages, the trophozoite and the cyst. The trophozoite is the active and motile stage, while the cyst is the environmentally resistant stage responsible for transmission. Dogs and cats are often infected by ingesting food or water contaminated with cysts. After ingestion, excystation occurs and the trophozoites are released into the intestine.7 In susceptible hosts, the trophozoites colonize the small intestine and replicate by binary fission. The trophozoites can either remain free in the intestinal lumen or attach to the mucosa via a ventral sucking disk. Cysts are formed as the organism transits down the colon.3 Infection is often spread via fecal-oral transmission of cysts either directly from infected individuals, or indirectly via contaminated fomites. As few as 10 Giardia cysts can initiate infection with the onset of disease ranging from an average of 8 days in dogs and 10 days in cats.3,4

Although Giardia may cause subclinical infections in some animals, the most common clinical sign is diarrhea which may be acute, intermittent, or chronic. The diarrhea is caused by malabsorption and hypersecretion of the intestines via a number of proposed mechanisms including toxin production, disruption of normal flora, inhibition of normal enterocyte enzymes, and microvilli blunting.6,8 The stool is usually pale and soft to watery with mucus. It often has a strong odor and steatorrhea may be present. Other clinical signs include abdominal discomfort, abdominal pain, and cramping. In immunocompetent animals, the diarrhea is usually self-limiting. However in animals with chronic diarrhea, weight loss may occur.3,7

The most definitive means of diagnosing giardiasis is by finding cysts or trophozoites in fecal samples as clinical signs and laboratory blood test results are often non-specific. In a wet mount of a fresh fecal smear, trophozoites may be detected but their absence does not rule out infection.4,7 Cysts and trophozoites can both be found in the stool within 5-7 days of infection.3 The trophozoites are tear-drop shaped and measure 15 x 8 um, while the cysts are crescent shaped and measure 12 x 7um.4 The zinc sulfate fecal flotation technique may also reveal Giardia trophozoites or cysts, and is superior to sugar flotation techniques as it is not as likely to distort the organisms. However as Giardia organisms are shed intermittently, it may be necessary to examine fresh fecal samples over 3-5 days.4 Other diagnostic tests include immunoflourescent assay (IFA), antigen detection by enzyme-linked immunosorbant assay (ELISA), and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay. The IFA is considered the reference standard by some parasitologists, but a disadvantage to this test is the necessity for specialized equipment. While multiple ELISAs are available commercially to detect Giardia cysts in feces, they should be supplemental to fecal flotation and wet mount evaluation. PCR testing is generally used to characterize the assemblages of Giardia duodenalis found in dogs and cats.7

Treatment for giardiasis include fenbendazole, metronidazole, or a combination of praziquantel, pyrantel, and febantel though there is no one treatment that is currently approved for dogs and cats. Permanent immunity does not occur after infection with Giardia, so re-infection is possible.6

Further information

The puppy was treated with fenbendazole and 2 weeks later, a recheck exam did not reveal the presence of Giardia.

References

1. Greenwood, S. University of Prince Edward Island, Atlantic Veterinary College. Department of Biomedical Sciences. Protozoan Parasites of Veterinary Importance. Available: http://people.upei.ca/sgreenwood/html/protozoa.html.

2. Giardia fact sheet: http://www.cfsph.iastate.edu/Factsheets/pdfs/giardiasis.pdf

3. Ballweber, L.R., Xiao, L., Bowman, D.D., Kahn, G. & Cama, V.A. 2010, “Giardiasis in dogs and cats: update on epidemiology and public health significance”, Trends in parasitology, vol. 26, no. 4, pp. 180-189.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention July 18, 2012-last update, Giardia and Pets. Available: http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/giardia/giardia-and-pets.html.

5. Mohamed AS, Levine M, Camp JW Jr, Lund E, Yoder JS, Glickman LT, Moore GE. Temporal patterns of human and canine Giardia infection in the United States: 2003-2009. Prev Vet Med. 2014 Feb 1;113(2):249-56

6. Thompson, R.C.A. & Smith, A. 2011, “Zoonotic enteric protozoa”, Veterinary parasitology, vol. 182, no. 1, pp. 70-78.

7. Tangtrongsup, S. & Scorza, V. 2010, “Update on the Diagnosis and Management of Giardia spp Infections in Dogs and Cats”, Topics in Companion Animal Medicine, vol. 25, no. 3, pp. 155-62.

8. Greene, C.E. 2006, Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat. 3rd Edition. Saunders Elsevier, St. Louis, Missouri.

Authored by: E. Behling-Kelly