Interpretation

Carcinoma with squamous differentiation and necrosis

Explanation

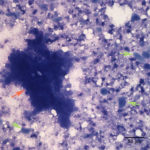

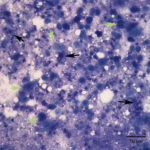

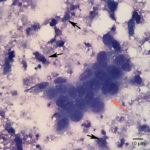

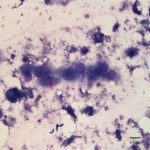

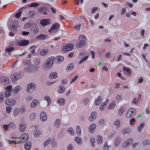

Fine needle aspirates of the kidney usually are poorly cellular and mainly comprised of peripheral blood with associated leukocytes and a few renal epithelial cells peppered in the sample. Rarely, in good aspirate, you may see fragments of renal tubules and glomeruli with Bowman’s capsules. In this case, the fine needle aspiration of the renal mass yielded variable numbers of small, cord-like disorganized clusters of epithelial cells on a thick blue to muddy purple, flocculent background of necrosis (black arrows). Both of these are uncommon and abnormal findings from renal aspirates (Question 1). The epithelial cells had defined cell borders with a moderate nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio and light blue to gray cytoplasm (Fig. 1 A and C). Their nuclei were round and centrally placed with coarsely stippled chromatin and 1-3 distinct nucleoli (Fig. 2). The cells displayed moderate anisocytosis and anisokaryosis. Admixed with the necrosis, and throughout the entire sample, there were many well-differentiated keratinized squamous epithelial cells (Question 3) (Fig. 1 A and B). The keratinocytes display substantial nuclear to cytoplasmic asynchrony characterized by cells having well-differentiated turquoise cytoplasm with angular boundaries with viable to pyknotic medium-sized coarse nuclei with indistinct nucleoli. Moderate numbers of anucleated keratinocytes were also present. The presence of these cells is also an abnormal finding in renal aspirates (Question 1).

The hypercalcemia (Question 2) in this case can be possibly explained by the renal disease this patient was experiencing. Nevertheless hypercalcemia due to renal disease is uncommon in dogs and cats and is more common in horses from decreased renal excretion of calcium. The most likely mechanism in this case that can explain the hypercalcemia would be hypercalcemia of malignancy related to production of parathyroid related protein (PTHrP) by the neoplasm.1 However, parathyroid hormone , PTHrP or vitamin D variants were not determined in this case.

Follow up

Unfortunately, given the invasiveness of the neoplasm and poor prognosis, the cat was humanly euthanized. A necropsy was performed.

On necropsy examination the right kidney appeared pale, tan and adhered to the dorsal abdominal wall. Both the right kidney and adrenal gland were found to be encapsulated in a 3.0 x 5.0 x 2.0 cm firm, smooth, ovoid white pale, tan mass that extended along the medial side of the right kidney and appeared to be centered on the renal artery and vein. On cut surface of the kidney/mass, the neoplasm appeared to be completely encapsulating the organ and could be cleanly peeled off the surface of the kidney with gentle traction. The lungs had multifocal mineralization and the left thyroid gland was 25% approximately larger than the right.

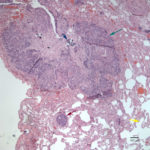

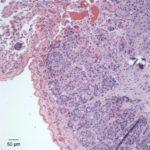

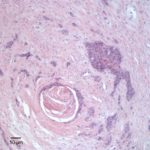

On histopathologic examination of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained section of tissues, there was a well-demarcated, unencapsulated, multinodular neoplasm (Fig. 3A) in the right lung, adjacent to the bronchus. The mass was comprised of epithelial cells forming islands, trabeculae and acini (Fig. 3B) that contained central pools of degenerate material and display abrupt keratinization (dyskeratosis) and individual necrosis (Fig. 3C). The cells displayed moderate anisocytosis and anisokaryosis with 25 mitotic figures in ten 400x fields. Concurrent findings in the lung included moderate multifocal arterial hypertrophy and hyperplasia, smooth muscle hyperplasia with mild edema, emphysema and atelectasis.

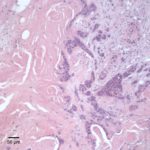

Similar neoplastic epithelial cells displaying abrupt keratinization were found starting at the hilus and infiltrating and expanding the renal capsule (Fig. 4A) with multifocal infiltration of the renal parenchyma, which showed large amounts of necrosis. The right adrenal gland was also affected but not overtly necrotic.

Given the epithelial neoplasm with glandular formation and squamous differentiation, along with the pattern of infiltration noted on the right kidney and adrenal gland, the final histologic diagnosis was a pulmonary adenosquamous carcinoma with metastasis to the kidney.

Discussion:

Primary renal neoplasms are not common in cats. Most of the reported cases are epithelial in origin, followed by mesenchymal and primitive tumors (e.g. nephroblastoma).2,3 Secondary (metastatic) tumors are far more common than primary renal tumors in kidneys of cats, with lymphoma being the most frequently seen tumor infiltrating the renal parenchyma.2 In this case, the tumor in the kidney was a metastatic site from an adenocarcinoma with squamous cell differentiation arising from the lung epithelium and spreading to the renal artery and vein. Vascular invasion can potentially explain the moderate thrombocytopenia, likely due to activation of hemostasis with increased consumption due to disruption of the vascular architecture and exposure of tissue factor from the sub-endothelial space. Alternatively, the tumor cells themselves may be expressing tissue factor or other procoagulant molecules, such as factor Xa.

Cats with primary lung tumors present with clinical signs referable to the respiratory tract, such as tachypnea, wheezing, dyspnea and non-productive cough; other clinical signs are associated with distant metastasis in other organs.4 In dogs and cats, neoplastic pleural effusions can occur secondary to the tumor.5 Some studies report that 75-80% of cats with primary pulmonary neoplasm already have metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis.2–4 In the cats, the most common primary pulmonary epithelial tumors are adenocarcinomas, followed by lower incidence of bronchioalveolar carcinoma and adenosquamous carcinoma.3

Pulmonary adenocarcinoma is a tumor that arises from the type II pneumocytes or Clara cells in the lung epithelium and tends to have a peribronchial pattern. A part of this neoplasm contained evidence of squamous differentiation of the epithelium. In order to classify a tumor as an adenosquamous carcinoma, some studies requires the the tumor to show >33% squamous differentiation.4 In human medicine, these neoplasms are diagnosed as adenosquamous carcinoma when both components (glandular and squamous) exceed 10%.6 Adenosquamous carcinomas comprised approximately 15% of all primary lung carcinomas in cats in one study.3 In dogs, this neoplasm less frequently metastasizes, but in the cat it appears to metastasize more rigorously, due to either biological differences or because the disease is far advanced at the time of diagnosis. Overall, pulmonary tumors greater than 3 cm in the dog are likely to show malignant behavior,2 however in the cat, the size of the neoplasm does not appear to predict behavior or prognosis, since smaller lesions usually display microscopic features of malignancy and invasion.2 Metastasis have been reported at regional lymph nodes, intrathoracic organs and distant organs such as the liver, spleen, kidney, skin, skeletal muscle and bone.2,3 The median survival time for pulmonary tumors in cats is almost 2 years for moderately differentiated tumors with surgical resection.3,7 In humans, adenosquamous carcinomas have a poorer prognosis than adenocarcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas combined and, in recent studies looking at molecular features, genetic mutations and extracellular matrix content of these tumors, suggests that adenosquamous carcinomas are a transition stage of an adenocarcinoma undergoing transdifferentiation to a squamous cell carcinoma.6

The hypercalcemia (Question 2) in this case is likely a paraneoplastic syndrome related to the underlying tumor. Hypercalcemia of malignancy due to parathyroid hormone related protein (PTHrP) secretion by the neoplasm has been previously reported in cats with bronchogenic adenocarcinomas.7 PTHrP has similar bioactivity as parathyroid hormone, which increases calcium concentrations by increasing the absorption of calcium in the proximal tubules of the kidney and by promoting bone resorption. Other mechanisms includes tumor infiltration in the bone with concurrent local osteolysis. Ectopic calcitriol (vitamin D3) production was thought to contribute to the hypercalcemia in a case report of a human patient with lung carcinoma.8 This could be another possible mechanism for the hypercalcemia in this case.

Common immunohistochemical markers used in human medicine and extrapolated to veterinary medicine for the characterization of lung tumors include thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1) and surfactant protein A (SP-A).3 Surfactant protein A is a component of the secretory product of normal pneumocytes in the lung. TTF-1 is expressed in the nucleus of follicular cells of the thyroid gland and in pneumocytes and is known to be important for differentiation of lung epithelium.3 About 80% of primary lung tumors expressed TTF-1 and SP-A in one study, which shows that these markers can be useful to characterize lung tumors in animals and likely identify the origin of the tumor at sites of metastasis.3 Unfortunately, immunohistochemical staining for these markers was not done in this case to confirm that the tumor in the kidney and artery were metastatic from the lung. However, the histologic pattern fit more with a metastatic tumor, rather than a true primary renal tumor.

Tracing back to this cat, the concurrent histological changes noted in the lung, including thickening or arteries, smooth muscle hyperplasia and increased peribronchial glands were suggestive of feline asthma and perhaps an underlying chronic inflammatory airway disease, which could have potentially predisposed this patient to malignant transformation of the pulmonary epithelium.

References

- Stockham SL, Scott MA. Calcium, Phosphorius, Magnesium, and their Regulatory Hormones. In: Fundamentals of Veterinary Clinical Pathology. Second. Blackwell Publishing; 2008. p. 593–638.

- Wilson DW. Tumors of the Respiratory Tract. In: Meuten DJ, editor. Tumors in Domestic Animals. Fith Editi. Wiley Blackwell; 2017. p. 467–98.

- D’Costa S, Yoon B-I, Kim D-Y, Motsinger-Reif a a, Williams M, Kim Y. Morphologic and molecular analysis of 39 spontaneous feline pulmonary carcinomas. Vet Pathol [Internet]. 2012;49(6):971–8. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21900542

- Hahn KA, Mcentee MF. Primary lung tumors in cats : 86 cases ( 1979 – 1994 ). Vol. 211, JAm Vet Med Assoc. 1997. p. 1257–60.

- Stewart J, Holloway A, Rasotto R, Bowlt K. Characterization of primary pulmonary adenosquamous carcinoma-associated pleural effusion. Vet Clin Pathol. 2016;45(1):179–83.

- Hou S, Zhou S, Qin Z, Yang L, Han X, Yao S, et al. Evidence, Mechanism, and Clinical Relevance of the Transdifferentiation from Lung Adenocarcinoma to Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Am J Pathol [Internet]. 2017;187(March):1–9. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28284717

- Schoen K, Block G, Newell SM, Coronado GS. Hypercalcemia of malignancy in a cat with bronchogenic adenocarcinoma. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2010;46(4):265–7.

- Nemr S, Alluri S, Sundaramurthy D, Landry D, Braden G. Hypercalcemia in Lung Cancer due to Simultaneously Elevated PTHrP and Ectopic Calcitriol Production: First Case Report. Case Rep Oncol Med [Internet]. 2017;2017:1–3. Available from: https://www.hindawi.com/journals/crionm/2017/2583217/

Author by: Drs. José Daniel Cruz Otero (clinical pathology resident) and Tracy Stokol