Interpretation:

Neutrophilic inflammation with Mycoplasma infection

Explanation:

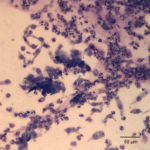

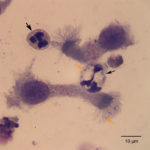

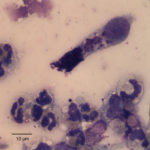

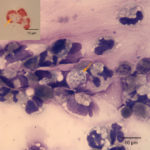

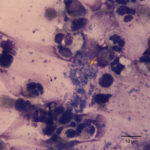

The tracheal wash was highly cellular and comprised primarily of inflammatory cells and respiratory epithelial cells (Question 1) admixed and occasionally entrapped in small amounts of light blue mucus and strands of nuclear streaming (from rupturing during smear preparation). The inflammatory cells were comprised primarily of degenerate and non-degenerate neutrophils (~96%) and lower numbers of macrophages and small lymphocytes. Low to moderate numbers of the neutrophils (often the degenerate ones) were noted to have moderate numbers of phagocytized organisms. These organisms were lightly basophilic, rod-to-ring-like in shape and about 1-2 um in size (Figure 1 and 4). They were found throughout the background, in dense pockets (Figure 5) and intimately associated with the cilia of the respiratory epithelial cells (Figure 2). They did not take up gram stain. Based on their morphologic features and location associated with cilia, a Mycoplasma spp. was considered likely. The macrophages occasionally displayed leukophagia of the neutrophils. The epithelial cells displayed mild atypia and were present in variably sized clusters but also, individualized throughout the sample. Increased numbers of goblet cells (Figure 3) were found peppered within the sample and likely represent a reactive response to chronic irritation or inflammation. These cells often contain abundant amounts of medium-sized, globular, and pink to magenta intracytoplasmic mucin granules.

Additional information:

Further diagnostics included aerobic, anaerobic and Mycoplasma cultures (Question 3). Results were as follow:

- Aerobic Bacterial Culture: No growth

- Anaerobic Bacterial Culture: No growth

- Mycoplasma Culture: Moderate Mycoplasma were isolated.

- Further speciation identified the organism as Mycoplasma bovirhinis.

The final clinical diagnosis was cranioventral pneumonia characterized by marked septic suppurative inflammation with cilia-associated Mycoplasma bovirhinis organisms.

Discussion:

Causes for pneumonia in cattle, often referred to as Bovine Respiratory Disease Complex (RBDC), includes bacterial diseases such as enzootic pneumonia, pneumonic mannheimiosis, respiratory histophilosis and Mycoplasma pneumonia. Viral causes such as infectious bovine rhinotracheitis (IBR), bovine herpesvirus 1 (BoHV-1), bovine parainfluenza virus 3 (BPIV-3) and bovine respiratory syncytial virus (BRSV) are also implicated in causing pneumonia and are believed to be the eliciting (primary) cause that predispose cattle to the secondary bacterial infections.1–4 Given the finding of phagocytized and cilia-associated bacteria in the tracheal wash, a bacterial pneumonia was at the top of our differential diagnostic list, but underlying viral causes are also possible (Question 2).

Bovine enzootic pneumonia is a multifactorial disease caused by a variety of etiologic agents that often cause disease in young calves. It is usually referred as calf pneumonia in where the interaction between host, environment and pathogen is crucial for the development of disease. The triggering agent(s) for disease are commonly related to a viral etiologies, such as the ones mentioned above, and other viral diseases not strictly related to direct pathology to the respiratory system (such as bovine viral diarrhea virus or bovine coronavirus). Viral infection is thought to predispose the host to invasion and disease by opportunistic bacteria such as Pasteurella multocida, Histophilus somni, Mannhemia haemolytica and Escherichia coli. The secondary bacterial infection is often the detrimental stage of the disease.

Mannheimia haemolytica, the cause of pneumonic mannheimiosis, is a commensal organism that resides in the nasopharynx and tonsils of normal cattle. It has been known to cause primary pneumonia, but the severity of disease is often associated with environmental stressors such as that associated with shipping (shipping fever) or concurrent viral or other bacterial infections.1,2,4,5 Mannheimia causes coagulative necrosis, severe fibrinonecrotic to hemorrhagic penumonia and vasculitis. Similar to Mannheimia, Histophilus somni, the cause of respiratory histophilosis, triggers similar respiratory pathologic changes in cattle, but concurrent vasculitis with thrombosis adds a neurological component to the infection with the latter pathogen.

Mycoplasma spp. are also a common cause of respiratory problems in cattle. Mycoplasmas are fastidious, prokaryotic microbes that are distinguished from bacteria because they lack a distinct cell wall. Species associated with respiratory infection include M. bovis, M. mycoides var. mycoides, M. dispar and rarely M. bovirhinis and M. alkalescens.1,2,4 Similar to the other bacterial pathogens, concurrent viral infection exacerbates disease. Historically, these patients are referred to as “not responding appropriately” to antibiotic therapy, with a portion of them remaining chronically ill and unthrifty for weeks after onset of disease. Clinically, patients can have a variety of respiratory signs including respiratory distress, coughing, nasal discharge, sinusitis and tachypnea. M. bovis is the most common isolated Mycoplasma causing pneumonia in cattle and can be also associated with mastitis, arthritis, tenosynovitis, myocarditis, pericarditis and keratoconjunctivitis.1,2,4 In calves, otitis, facial paralysis and vestibular disease are also some manifestations of M. bovis infection.6 Dark, red firm consolidated lobules of cranioventral lungs are commonly seen during post-mortem examination. These regions of consolidation may have white to yellow nodules characterized by coagulative necrosis surrounded by layers of neutrophils, macrophages, lymphocytes and plasma cells. Similar nodular necrotic foci can be observed in other organs, such as the kidney, liver, joints and heart.1,2 On a side note, Bison bison (North American bison) are highly susceptible to M. bovis leading to reproductive problems and severe, sometimes fatal, disease that affects predominantly mature adults.7,8

Contagious Bovine Pleuropneumonia, caused by M. mycoides var. mycoides, is reported to have been eradicated from North America since 1892 and Australia in the 1970s. However, this subspecies of Mycoplasma is still a common pathogen in Africa, Asia and Eastern Europe. It is considered one of the most pathogenic Mycoplasma from those that cause disease in domestic animals. Infection occurs through inhalation of contaminated aerosols. The pathogenesis is not completely understood, but toxins, unregulated production of tumor necrosis factor-α, ciliary dysfunction, immunosuppression and vasculitis with thrombosis are suspected mechanisms. Lesions are similar to those caused by M. haemolytica (fibrinonecrotic pneumonia), but more severe with vasculitis and thrombosis causing marked ischemic injury. Vaccination is available and an effective preventive of disease.

In this case, the calf had a positive growth of Mycoplasma bovirhinis, which is an uncommon cause of pneumonia in cattle. M. bovirhinis has been reported to be a common organism found in the airways in cattle, but prevalence seems to vary depending on the breed and management practices.9,3 It is often isolated in conjunction with M. dispar and is though that their main pathogenic role is exacerbating disease caused by more pathogenic organisms such as M. bovis.9 In experimental studies, M. bovirhinis did not cause disease after inoculation and M. dispar did cause pneumonia, but it was not severe.10 Likely, the fracture along with the prolonged recumbency due to immobility was a strong stressor factor that predisposed this calf to a secondary bacterial infection with M. bovirhinis (commensal organism). However, a primary viral infection could have set the bed for this opportunistic organism to cause disease, since other causes for respiratory disease were not completely ruled out at the time of the tracheal wash. It is worth mentioning that despite this calf having septic suppurative pneumonia and a fracture; there was only mild inflammation evident on the blood results (presumptive reactive thrombocytosis, hyperfibrinogenemia, low iron and TIBC). The bull calf was placed on a course of antibiotic therapy and a culture for Mycoplasma was negative after treatment. The calf underwent orthopedic surgery and recovered uneventfully.

References

- Zachary JF. Mechanisms of Microbial Infections1. Pathol Basis Vet Dis [Internet]. 2017;132–241.e1. Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/B9780323357753000047

- López A, Martinson SA. Chapter 9 – Respiratory System, Mediastinum, and Pleurae1. Pathol Basis Vet Dis (Sixth Ed [Internet]. 2017;(2):471–560.e1. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780323357753000096

- Thomas A, Ball H, Dizier I, Trolin A, Bell C, Mainil J, et al. Isolation of Mycoplasma species from the lower respiratory tract of healthy cattle and cattle with respiratory disease in Belgium. Vet Rec. 2002;151(16):472–6.

- Woolums AR. Diseases of the Respiratory System: Ruminant Respiratory System. In: Large Animal Internal Medicine. Fith. Mosby; 2014.

- Rajeev S, Kania SA, Nair R V., McPherson JT, Moore RN, Bemis DA. Bordetella bronchiseptica fimbrial protein-enhanced immunogenicity of a Mannheimia haemolytica leukotoxin fragment. Vaccine. 2001;19(32):4842–50.

- Lamm CG, Munson L, Thurmond MC, Barr BC, George LW. Mycoplasma otitis in California calves. J Vet Diagnostic Investig. 2004;16(5):397–402.

- Janardhan KS, Hays M, Dyer N, Oberst RD, DeBey BM. Mycoplasma bovis outbreak in a herd of North American bison (Bison bison). J Vet Diagn Invest [Internet]. 2010;22(5):797–801. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20807947%5Cnhttp://vdi.sagepub.com/content/22/5/797.full.pdf

- Register KB, Woodbury MR, Davies JL, Trujillo JD, Perez-Casal J, Burrage PH, et al. Systemic mycoplasmosis with dystocia and abortion in a North American bison (Bison bison) herd. J Vet Diagnostic Investig. 2013;25(4):541–5.

- Bottinelli M, Passamonti F, Rampacci E, Stefanetti V, Pochiero L, Coletti M, et al. DNA microarray assay and real-time PCR as useful tools for studying the respiratory tract Mycoplasma populations in young dairy calves. J Med Microbiol. 2017;66(9):1342–9.

- Gourlay RN, Howard CJ, Thomas LH, Wyld SG. Pathogenicity of some Mycoplasma and Acholeplasma species in the lungs of gnotobiotic calves. Res Vet Sci. 1979 Sep;27(2):233–7.

Authors: José Daniel Cruz Otero (resident), edited by Tracy Stokol