Canine

Mycoplasma haemocanis (formerly Haemobartonella canis) rarely causes anemia in dogs with normal spleens and normal immune systems. Clinical anemia can develop when a carrier dog is splenectomized or when a splenectomized dog is transfused with blood from a carrier donor. M. haemocanis may be a widespread latent infection in kennel-raised dogs. These dogs are commonly used for research worldwide and the potential exists for such chronic infections to confound research results obtained from these animals. Splenic tumors or infarction, treatment with immunosuppressive drugs, and concurrent infection with Babesia, Ehrlichia, and bacterial or viral diseases can also render a dog vulnerable to acute disease. Experimental transmission of the parasite has been accomplished using the brown dog tick (Rhipicephalus sanguineus). Clinical signs and hematologic findings are those usually associated with an extravascular hemolytic anemia.

There are a few reports of a small hemoplasma, M. haematoparvum, in dogs. This organism is closely related to the feline bacterium, M. haemominutum. The significance of infection in dogs with this bacteria is largely unknown.

Feline

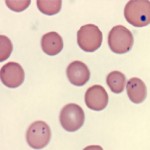

Mycoplasma haemofelis (formerly Haemobartonella felis) is an epicellular bacterial parasite of feline erythrocytes that can cause hemolytic anemia. In blood smears stained with polychrome stains, the organisms are recognized as small blue cocci, rings, or rods on the edges or across the faces of red cells. Stain precipitate is often mistaken for organisms, resulting in unnecessary tetracycline administration.

The hemolytic anemia caused by M. haemofelis is called Feline Infectious Anemia (FIA) and is usually regenerative in nature (unless underlying disease suppresses the regenerative response, e.g. Feline Leukemia Virus infection). Therefore, non-regenerative anemia in a cat with M. haemofelis necessitates further evaluation for another disease process and should not be wholly attributed to M. haemofelis infection. In this situation, it is likely that the underlying disease lead to recrudescence of M. haemofelis in an asymptomatic carrier. An exception is in acute M. haemofelis infection, where there has not been sufficient time for a bone marrow reponse.

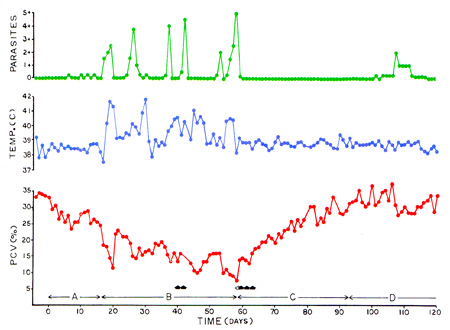

In Feline Infectious Anemia, the parasitemia is episodic, with decreasing hematocrits at times of parasitemia. Because of the cyclic parasitemia, organisms may be numerous, scarce or not found in a given blood sample as illustrated in the graphs below.

Absence of organisms is thought to be due to transient sequestration of parasitized erythrocytes in the spleen with removal of organisms and release of erythrocytes with reduced lifespans. The severity of the anemia does not correlate to the degree of parasitemia, and is often worse in animals with underlying disease. Cats are often concurrently Coombs positive and can display cold agglutination (agglutination is often observed in blood tubes stored in the refrigerator). Thrombocytopenia may also be observed in some cats. Icterus is quite uncommon due to M. haemofelis infection alone. Most cats infected with M. haemofelis become asymptomatic carriers and re-develop milder versions of the disease when stressed.

Diagnosis of M. haemofelis is accomplished by detection of the organism in blood smears. As mentioned above, organisms may not be detected because of the cyclic parasitemia, with dwindling parasite numbers. Note that the organism falls off erythrocytes in aged blood samples (> 24 hours) and can be mistaken for stain precipitate as they are found between and not on the erythrocytes, as expected. This can result in misdiagnosis. Newer PCR-based diagnostic tests are becoming more commercially available and are very useful in cats with low parasitemias or that are subclinical carriers.

Mycoplasma haemominutum is a small red cell parasite that causes only minimal clinical signs of acute disease and negligible hematologic changes in infected cats. Single, and occasionally, multiple organisms are detected on each red blood cell, however they are far more difficult to see than M. haemofelis. The difference in virulence between these two red cell parasites (M. haemofelis and M. haemominutum) in the cat might be merely a dose dependent effect. It has been suggested that hemoplasma infections in cats can exacerbate the progression of FeLV-related diseases.

Fleas infected with M. haemofelis can transmit parasites and produce disease in a susceptible cat, whereas the experimental transmission of M. haemominutum by fleas was not successful. Although treatment with doxycycline or enrofloxacin may control acute infections in the cat, none of the antibiotics tested to date consistently clear the parasites permanently from the animal, resulting in a chronic carrier state.

Bovine

Mycoplasma wenyonii (formerly Eperythrozoon) is the mycoplasma hemoparasite species that affects cattle. The clinical signs are unusual, consisting of acute onset hindleg and scrotal (males) or udder (females) swelling. Cattle are febrile and cows have decreased milk production. It appears to be especially prevalent in post-partum heifers. In bulls, the parasite may cause decreased fertility due to testicular degeneration. The disease appears to be seasonal in summer to fall. Affected cattle are anemic (usually non-regenerative), with mild thrombocytopenia. Organisms are observed attached to erythrocytes and free in the cytoplasm. During the acute phase, infected animals have mild lymphadenopathy, fever and musculoskeletal stiffness. Signs often last for 2-5 days, then resolve.

Porcine

Mycoplasma suis and Mycoplasma parvum (formerly Eperythrozoon spp.) are uncultivated, wall-less bacteria of swine that parasitize the surface of erythrocytes. The presence of two distinct species in pigs was established by cross-inoculation studies. Furthermore, they differ in size (M. suis varies from 1 µm to 2.5 µm whereas M. parvum is smaller at 0.5 µm) and degree of parasitemia (with M. suis, many parasites are often observed, whereas with M. parvum, the parasitemia is low).

M. suis can produce a clinical hemolytic anemia in young pigs under natural conditions, but infections with M. parvum do not cause overt disease. The clinical syndrome associated with M. suis infection has been called the ictero-anemia of pigs. The disease may appear as severe acute anemia with fever, icterus, anorexia, depression and muscle weakness. Parasitemia is high during the early stage of clinical disease but disappears rapidly as the reticulocyte count rises. Subclinical disease may compromise breeding performance and weight gain. Transmission is by the common hog louse (Haematopinus suis). The disease is diagnosed by identification of the parasite in blood smears, serology (IHA and ELISA) and PCR-based techniques.

Camilidae

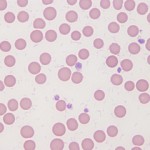

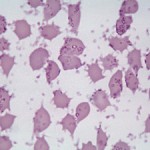

Mycoplasma haemolamae (formerly Eperythrozoon) infections have been recognized in llamas and alpacas. Younger animals are more susceptible to acute infection, leading to massive parasitemia, which has been associated with anemia. The anemia is poorly regenerative (even though nucleated red blood cells may be seen). In cases with high parasitemia, many red blood cells are coated with organisms having ring, cocci, and rod shapes (see image to the right). The organisms detach from the red blood cell surface with storage (as soon as 1 hour after collection; this is exacerbated by refrigeration). Llamas with chronic infections may have multiple clinical problems, including ill-thrift and poor weight gain, thought to be due to abnormal immunologic function. Whether the organism is associated with anemia is a matter of debate. We have seen cases of severe parasitemia in animals without anemia. In 34 clinically healthy non-anemic camelids, animals that were PCR-positive did not have lower red blood cell counts, packed cell volumes or hemoglobin concentrations than PCR-negative animals (Viesselmann et al 2019). Similar findings were obtained in an earlier study of Peruvian and Chilean animals (Tornquist et al 2010). However, none of the animals had organisms in blood and it is likely they were asymptomatic carriers (and could have had low parasitemias).